Juneteenth celebrations marking the end of slavery in the United States go back to an order issued as Union troops arrived in Texas at the end of the Civil War. It declared that all enslaved people in the state were free and had "absolute equality."

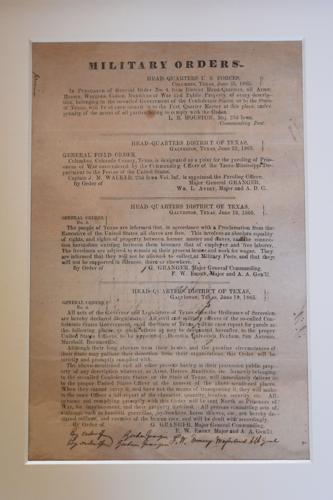

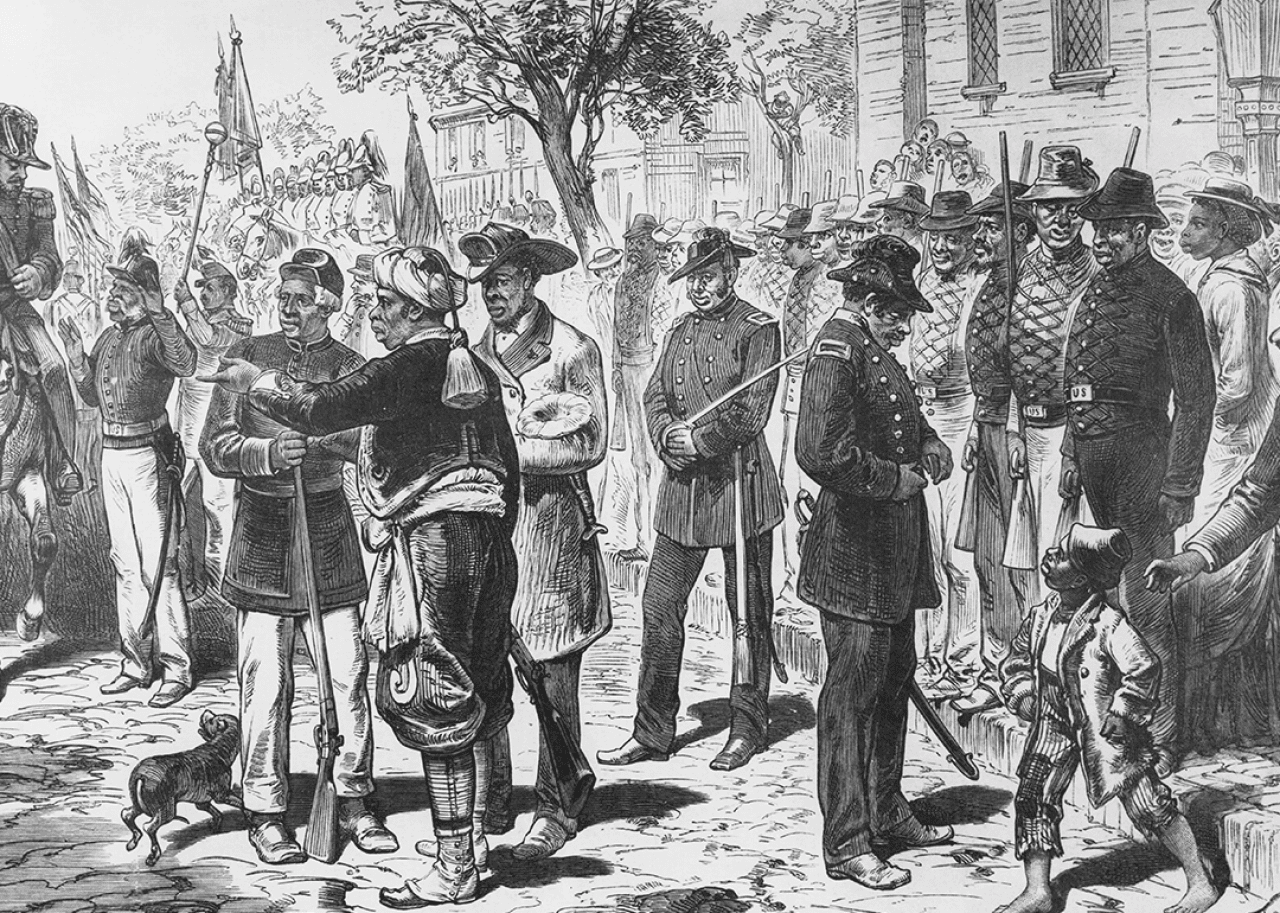

Word quickly spread of General Order No. 3 — issued June 19, 1865, when U.S. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger landed in the South Texas port city of Galveston — as troops posted handbills and newspapers published them.

The Dallas Historical Society will put one of those original handbills on display at the Hall of State in Fair Park starting June 19.

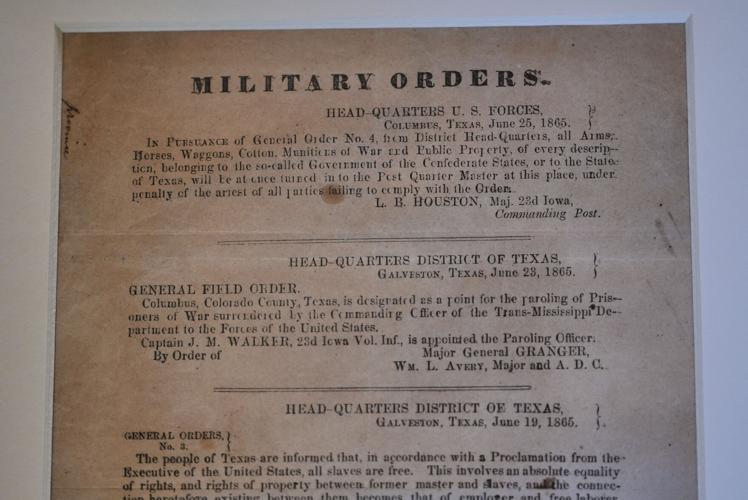

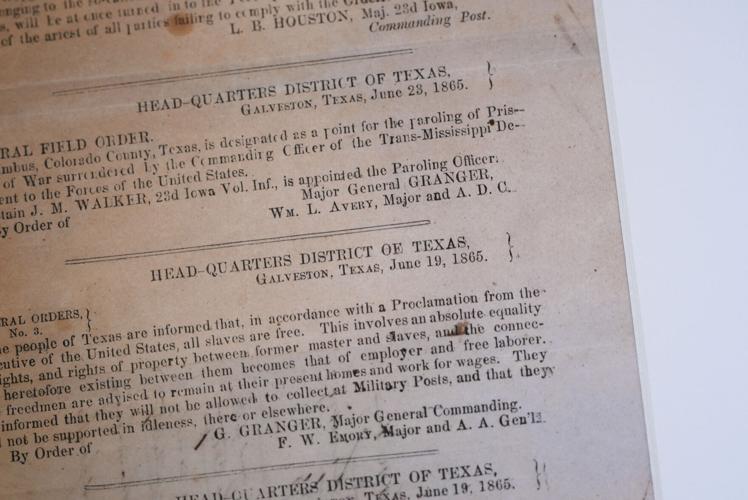

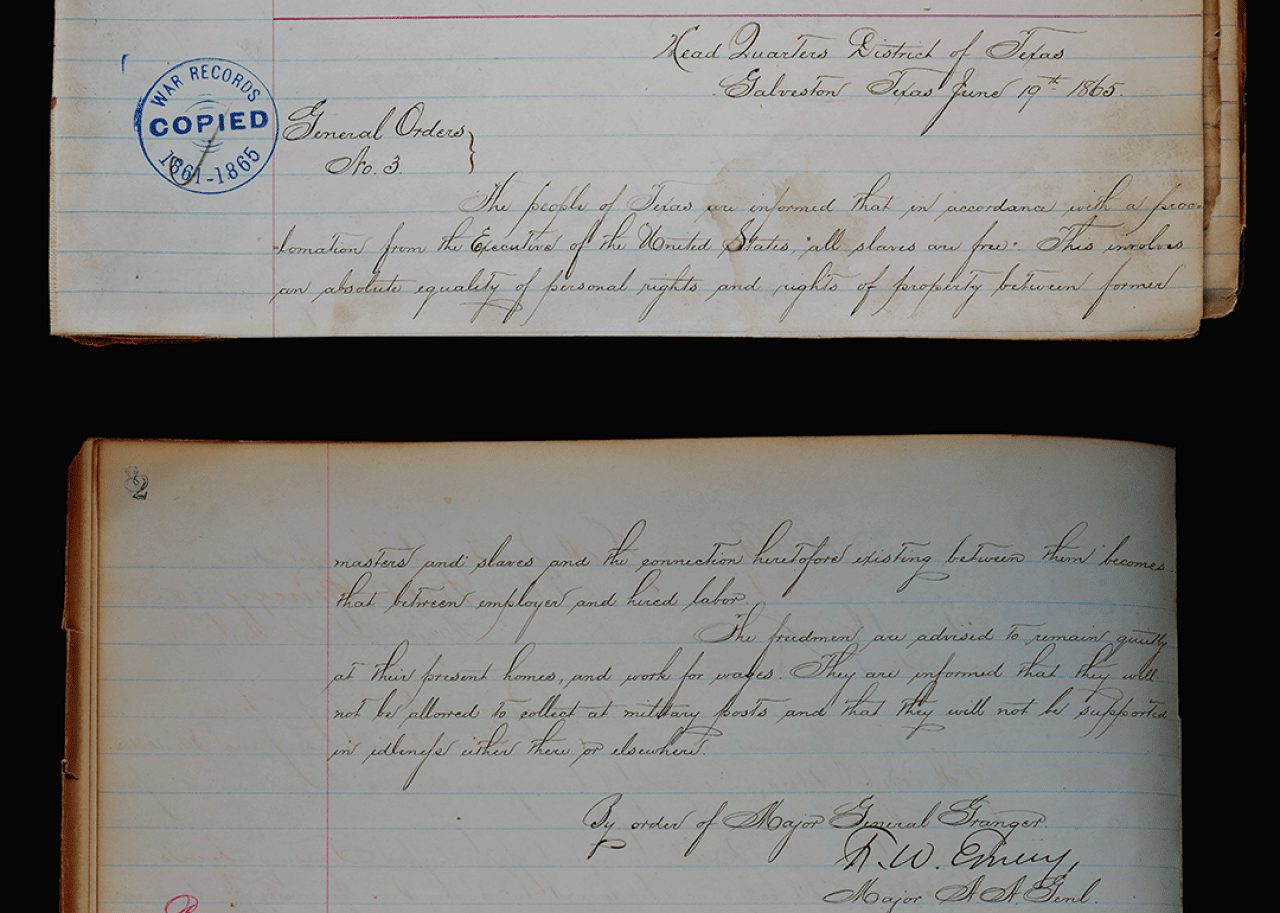

A section of the 1865 General Order No. 3.

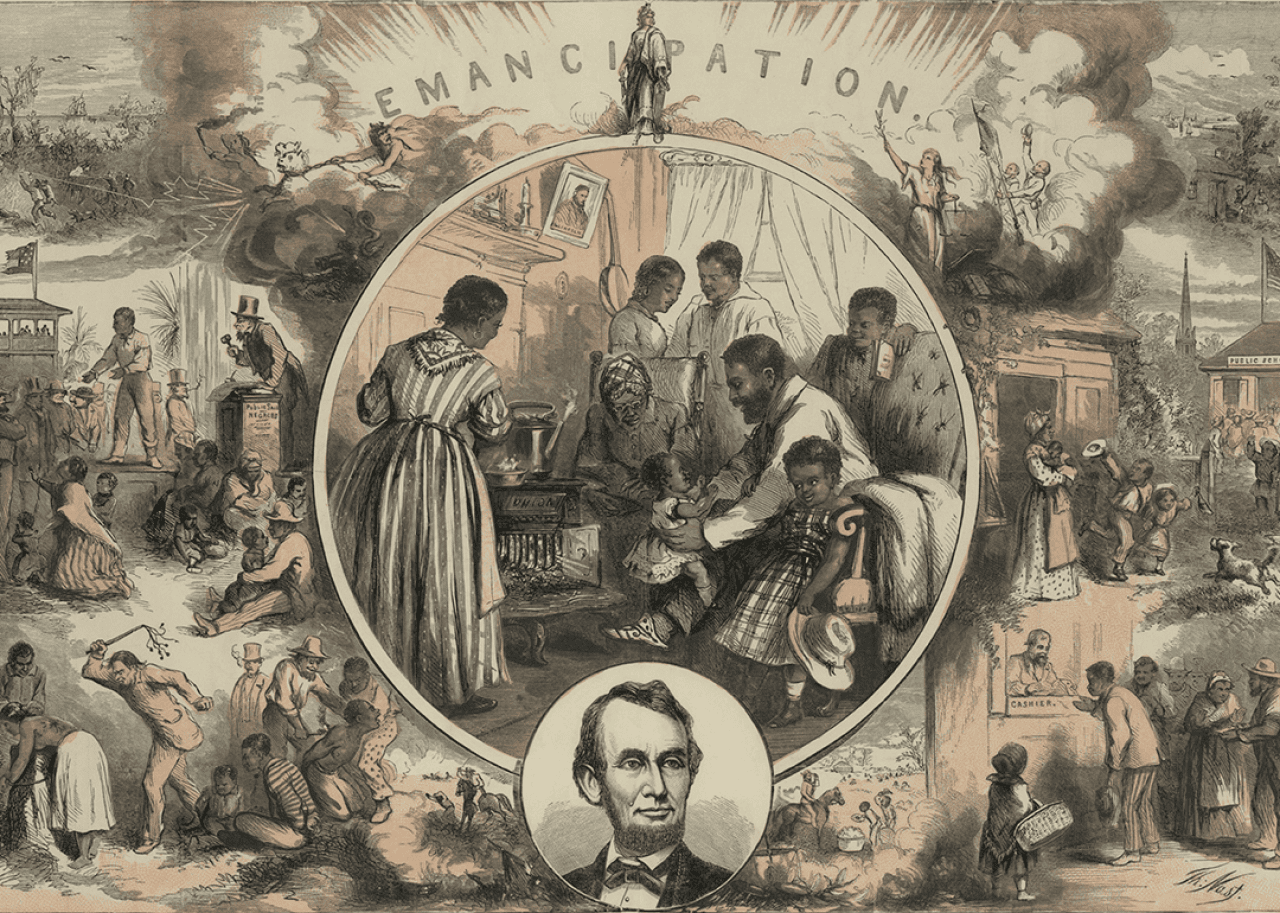

Juneteenth became a federal holiday in the U.S. in 2021 but has been celebrated in Texas since 1866. Later, communities in other states also marked the day.

"There'd be barbecue and celebrations," said Portia D. Hopkins, the historian for Rice University in Houston. "It was really an effort for people to say: Look at how far we've come. Look at what we've been able to endure as a community."

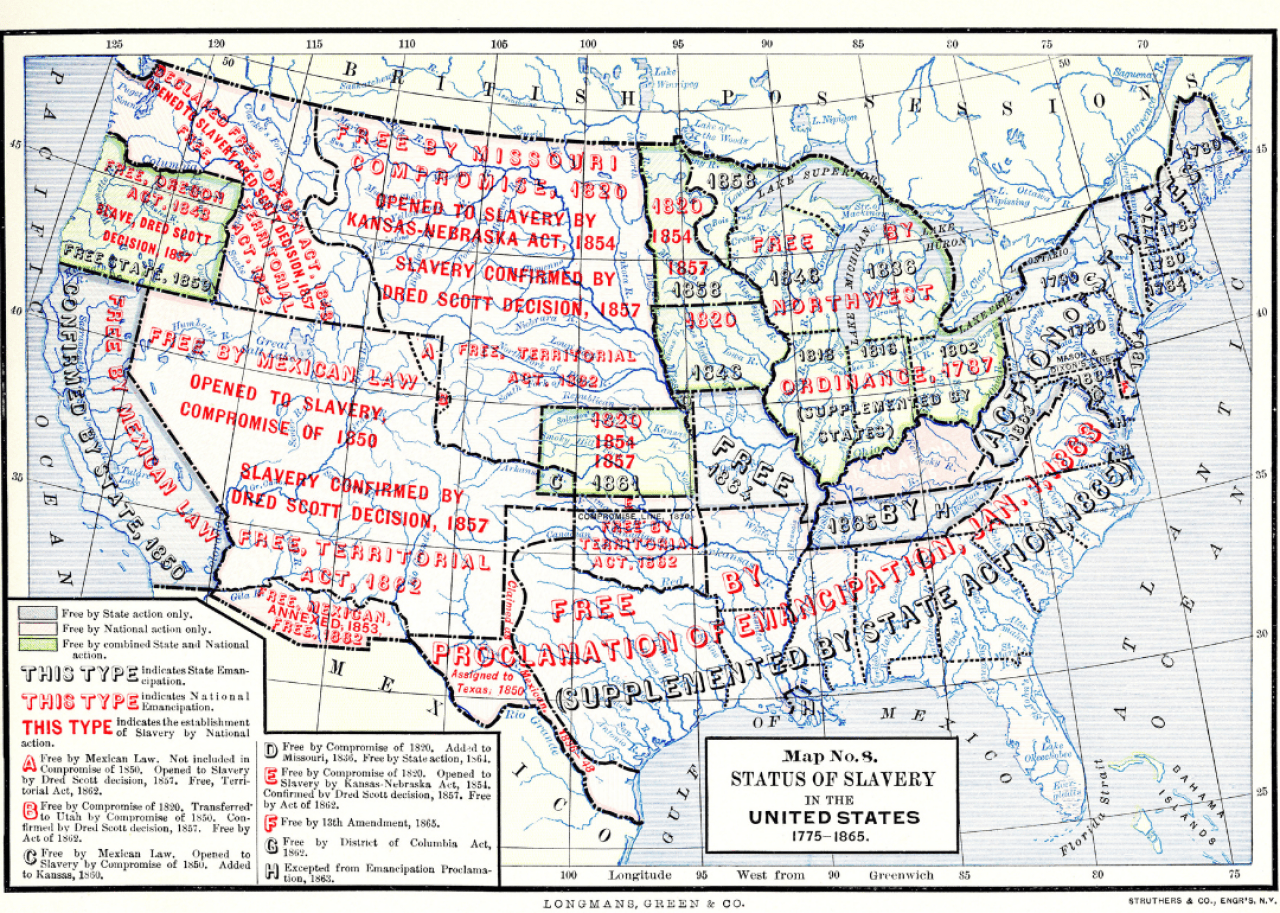

Progression of freedom

On Jan. 1, 1863, nearly two years into the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the freedom of "all persons held as slaves" in the still rebellious states of the Confederacy.

That didn't mean immediate freedom. "It would take the Union armies moving through the South and effectively freeing those people for that to come to pass," said Edward T. Cotham Jr., a historian and author of the book "Juneteenth: The Story Behind the Celebration."

The proclamation didn't apply to the border states that allowed enslavement but didn't leave the Union, nor the states occupied by the Union at the time, said Erin Stewart Mauldin, chair of southern history at the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg.

"You have to think of emancipation as a patchwork," she said. "It doesn't happen all at once. It is hyper local."

Still, she said, the proclamation "was recognized immediately as this watershed moment in history." It was "the promise that the end of slavery is now a war aim," she said.

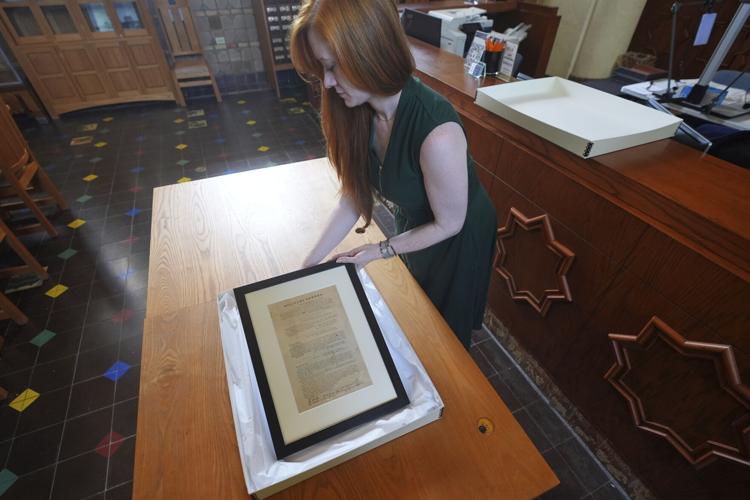

Kaitlyn Price, curator of collections for the Dallas Historical Society, displays the 1865 Juneteenth General Order No. 3 on June 6 at the Fair Park Hall of State in Dallas.

Texas at war's end

As the war progressed, many enslavers from the South fled to Texas, causing the state's enslaved population to balloon from about 182,000 in 1860 to 250,000 by the end of the war in 1865, Mauldin said.

Cotham said that while enslaved people were emancipated "on a lot of different dates in a lot of different places across the country," June 19 is the most appropriate date to celebrate the end of slavery because it represents the "last large intact body of enslaved people to be freed."

He said many enslaved people across the South knew of the Emancipation Proclamation, but that it didn't mean anything until troops arrived to enforce it.

About six months after General Order No. 3 was issued, Congress ratified the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery.

General Order No. 3

The 1865 General Order No. 3 is displayed June 6 by the Dallas Historical Society at the Fair Park Hall of State in Dallas.

The order begins by saying "all slaves are free" and have "absolute equality" of rights. Going forward, the relationship between "former masters and slaves" will be that of employer and hired laborer.

It advises freedmen to "remain at their present homes and work for wages," adding they must not collect at military posts and "will not be supported in idleness."

The handbills also were handed out to church and local officials. Cotham said Union chaplains would travel from farm to farm to explain the order to workers, and many former enslavers read the order to the people they enslaved, emphasizing the part about continuing to work.

The Dallas Historical Society's handbill came from the collection of newspaperman George Bannerman Dealey, who founded the society, said Karl Chiao, the society's executive director. Dealey began working at a Galveston newspaper in 1874 before the publisher sent him to Dallas to start The Dallas Morning News.

Chiao said their handbill is the only one they know of that still exists. The National Archives holds the official handwritten record of General Order No. 3.

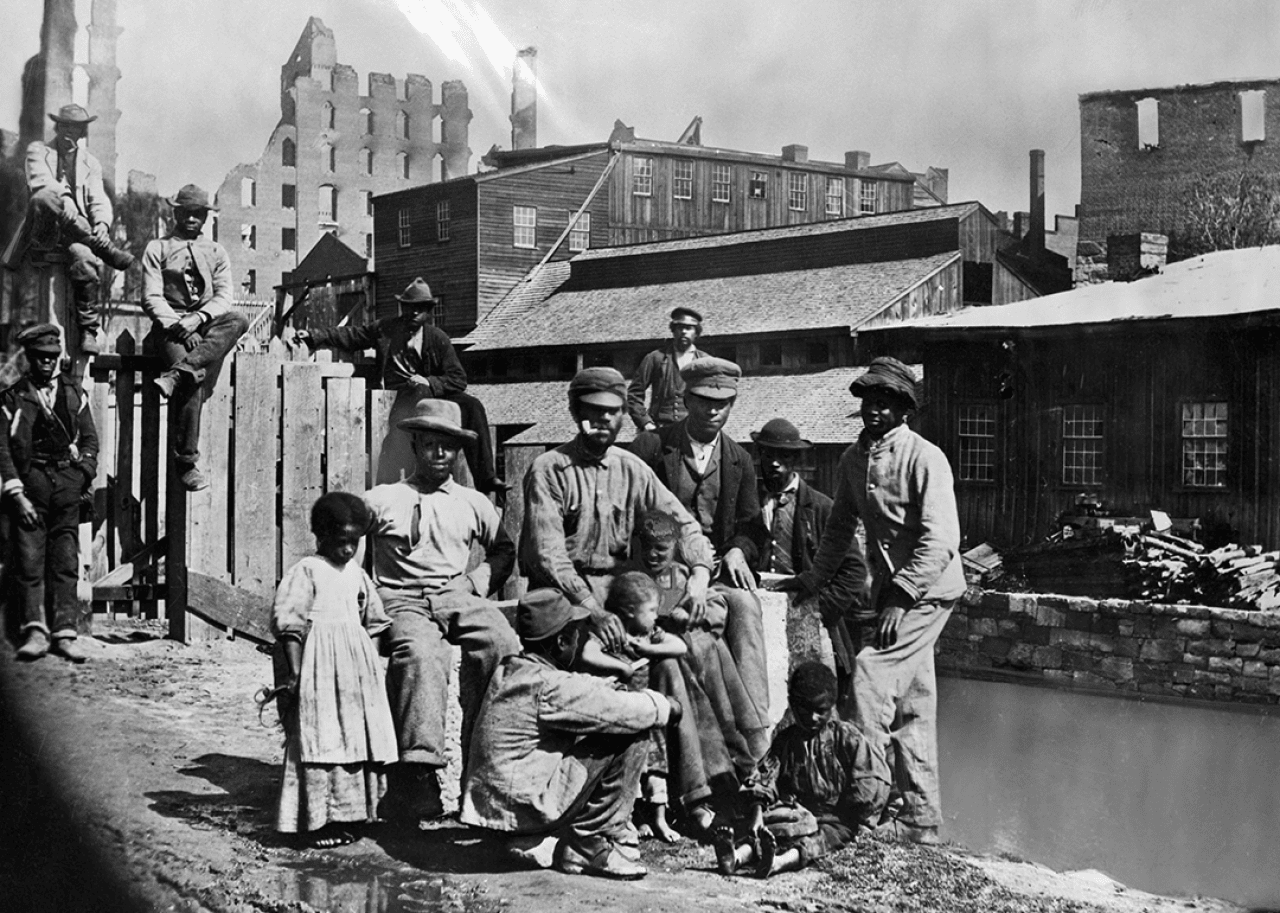

What freedom looks like

A section of the 1865 General Order No. 3.

"Some of the people who were set free stayed on the plantations and worked for their former owners, others left, they went to Houston, to Dallas, or they went to San Antonio seeking work," said W. Marvin Dulaney, deputy director of the African American Museum of Dallas.

While there was excitement, the newly freed people knew they had to "build up what citizenship looked like for them," Hopkins of Rice University said, and there was still "a lot of work to do."

"You changed the relationship between the enslaver and the enslaved but you didn't change the culture or the societal norms with how enslavers treated enslaved people," she said.

Mauldin said participants in early Juneteenth celebrations were "incredibly brave," noting that by 1868, the Ku Klux Klan was established in Texas. They were celebrating their freedom, she said, "under constant threat of violence."

The history and significance of Juneteenth

![]()

The history and significance of Juneteenth

Juneteenth—also known as Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, or the country's second Independence Day—stands as an enduring symbol of Black American freedom. When Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger and fellow federal soldiers arrived in Galveston, a coastal town on Texas' Galveston Island, on June 19, 1865, it was to issue orders for the emancipation of enslaved people throughout the state.

Although telegraph messages had spread news of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and while the war had been resolved in the Union's favor since April of 1865, Granger's message represented a promise of accountability. There was now a large enough coalition to enforce the end of slavery and to overturn the Texas Confederate constitution, which forbade individuals' release from bondage.

In this way, Texas became the last Confederate state to end slavery in the United States.

Though celebrated for hundreds of years in parts of the U.S., Juneteenth's history and significance have only recently gained massive national attention. The historic date was not recognized as a federal holiday until 2021, more than a century and a half after it took place.

Today, Juneteenth is commonly commemorated with public art, festivals, and civic engagement across the country. In 2025, the long-awaited National Juneteenth Museum opened its doors in Fort Worth, Texas, guided by the staunch efforts of activist Opal Lee, who is widely regarded as the "Grandmother of Juneteenth." Meanwhile, cities like Atlanta, Detroit, and Philadelphia have expanded their Juneteenth programming, incorporating everything from economic justice panels to Black-led farmers markets.

The holiday has also sparked renewed debates over how schools teach slavery and Reconstruction, particularly in light of state-level restrictions on curricula addressing racism and Black history. In this moment, Juneteenth has become not just a day of remembrance; it's a reflection of ongoing struggles for equity and historical truth.

Stacker explored the history and significance of Juneteenth by examining historical documentation, including texts for General Order #3 and the Emancipation Proclamation. Stacker also researched the lasting significance of this historic day while clarifying some of the most egregious misinformation about it.

Juneteenth commemorates the 1865 delivery of General Order #3

Maj. Gen. Granger was given command of the District of Texas following the Civil War's conclusion, making him an obvious choice for delivering General Order #3.

In its simplest terms, General Order #3 declared that all enslaved people in Texas were free; but the order maintained racist undertones and encouraged enslaved people to stay where they were being held to continue work—this time for wages as free men and women.

The order's handwritten record, preserved at the National Archives Building in Washington D.C., reads:

"The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."

Chattel slavery in all states wasn't abolished until the end of 1865

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed into law by President Lincoln on Jan. 1, 1863, called for an end to legal slavery in secessionist Confederate states only, impacting about 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country at that time. As the war drew to a close and Union soldiers retook territory, enslaved people living in those areas were liberated.

Lincoln's decision to free only those enslaved individuals in bondage in Confederate states was a strategic, militaristic method, as he notably did not free those enslaved in Union states. Further, the proclamation was unenforceable. Still, Union troops fighting in the war brought news of emancipation along with the military might to enforce it. Many enslaved people were motivated enough by the news to risk fleeing and seek safety in Union states or by joining the U.S. Army and Navy to help fight.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, any enslaved person who escaped over Union lines or to oncoming federal troops during the war was free in perpetuity.

Maj. Gen. Granger's orders on June 19, 1865, released enslaved people in Texas from bondage. But it was another six months before the last two states—Delaware and Kentucky—freed enslaved people, and only when the 13th Amendment was ratified on Dec. 18, 1865.

The 13th Amendment officially ended slavery and involuntary servitude at the federal level, except as a punishment for a crime. That loophole has been capitalized upon since the amendment passed. Kentucky officially adopted the 13th Amendment in 1976.

Juneteenth celebrations originated in Galveston, Texas, starting in 1866

Mixed reactions followed Granger's proclamation.

Many newly freed people remained on former enslavers' properties to work for pay, while others immediately fled north or into nearby states like Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma to reunite with family. As people fanned out around the country, they took Juneteenth celebrations along with them. Formerly enslaved people and their descendants also made yearly pilgrimages back to Galveston to memorialize the date's significance.

Juneteenth became an official Texas holiday in 1980.

While Juneteenth is among the oldest celebrations of emancipation, it is not the oldest. That distinction goes to Gallipolis, Ohio, which has celebrated the end of slavery there since Sept. 22, 1863.

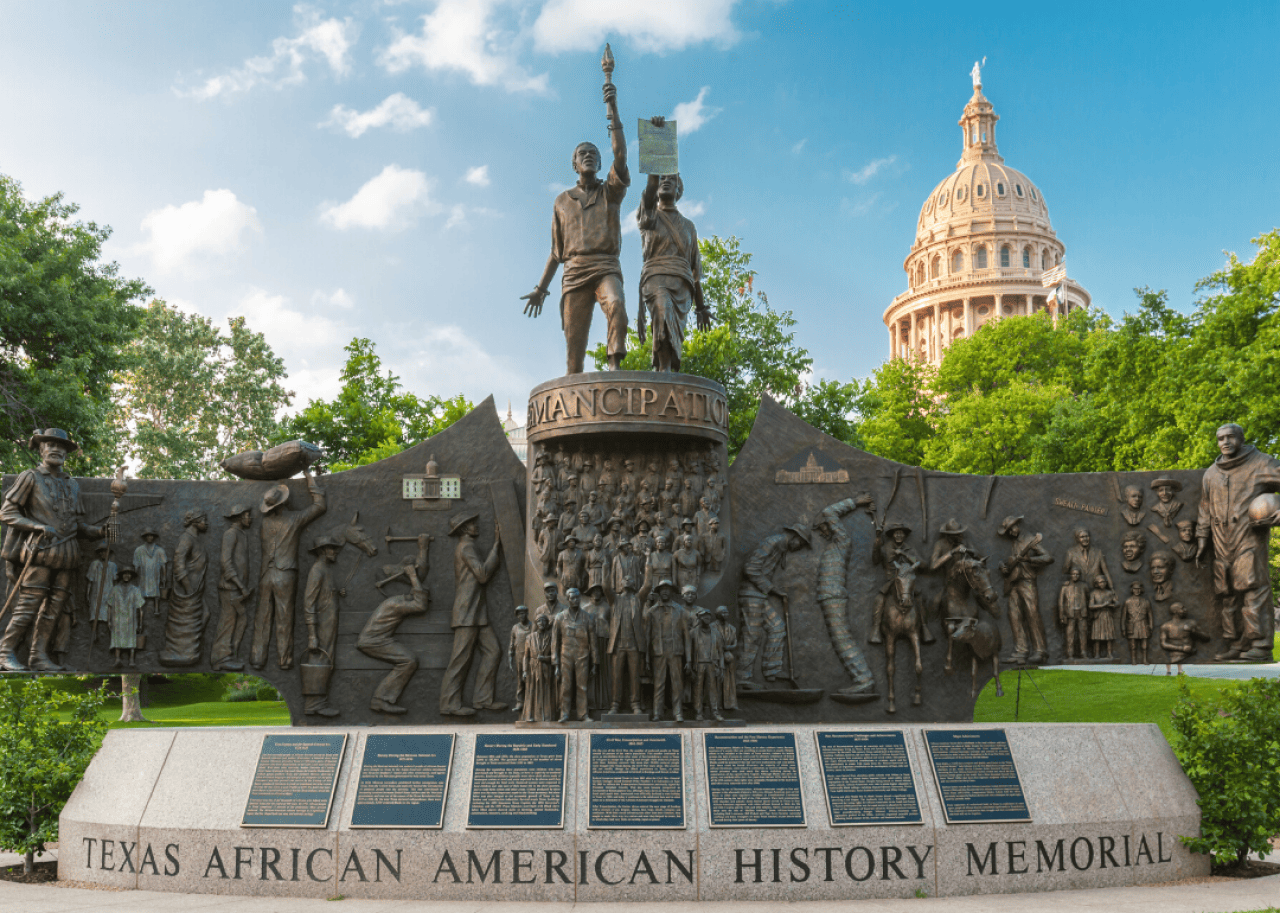

The first land to commemorate and celebrate the event was purchased in 1872 and is now a public park

Formerly enslaved African American ministers and businessmen got together in 1872 to raise the $1,000 necessary to buy 10 acres of land in Houston's Third and Fourth wards. They called the lot Emancipation Park.

The park was donated to the city of Houston in 1916. In the late 1930s, the Public Works Administration, which was established as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, constructed a recreation center and public pool on the park site. The Houston City Council declared the park a protected historic landmark on Nov. 7, 2007.

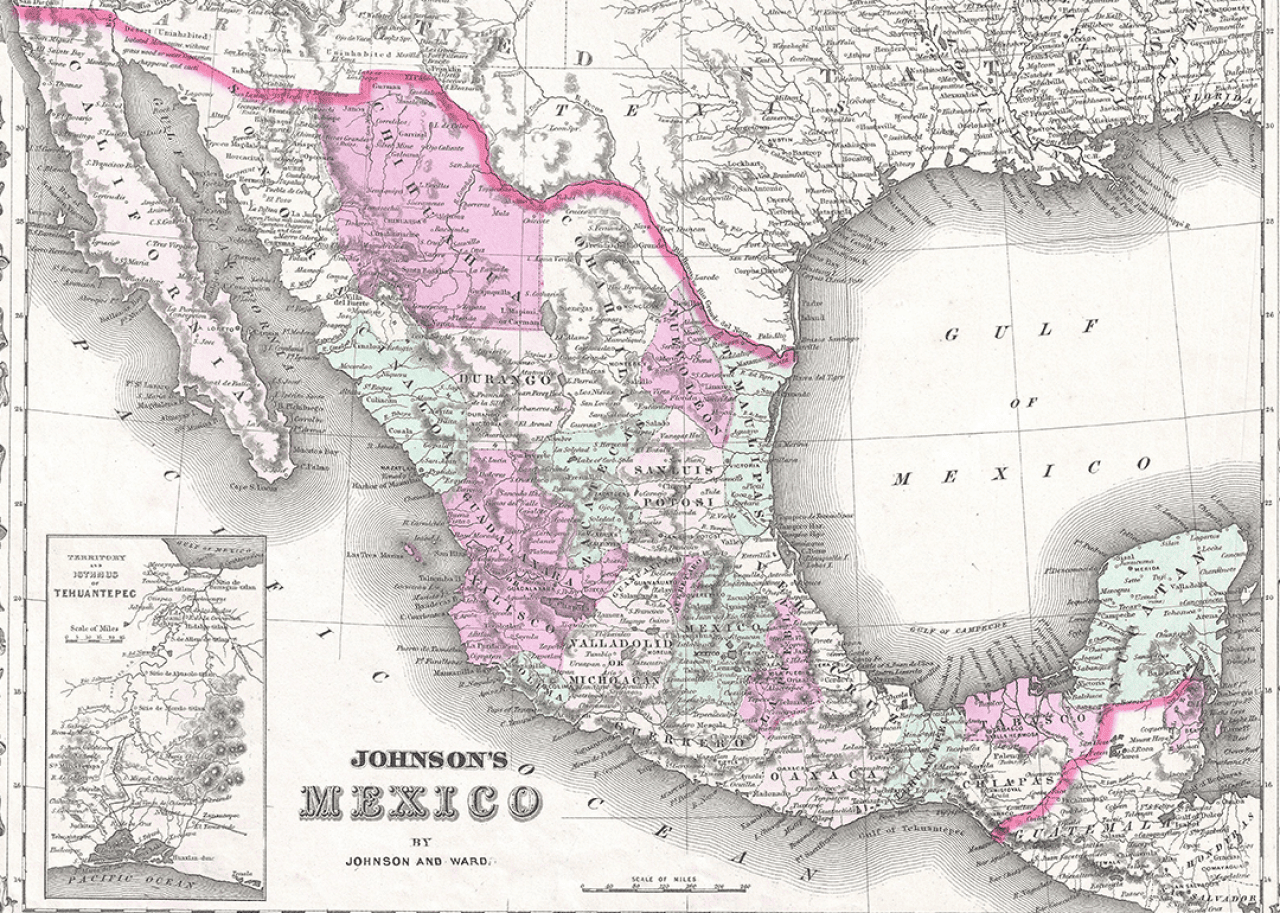

Juneteenth has been celebrated in Mexico for more than 150 years

Mexico was a longtime sanctuary for those who escaped chattel slavery, with a Southern Underground Railroad that helped as many as 10,000 people flee bondage. Descendants of enslaved people who also emigrated over the southern border from the U.S. brought with them a tapestry of histories and traditions, including the Juneteenth celebration.

Juneteenth has been celebrated in a small Mexican village called Nacimiento since 1870.

The last enslaved people in the US weren't adopted as citizens until 1885

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War and had members who enslaved Black women, children, and men. Following the Civil War's conclusion, the Choctaws did not grant those who were enslaved their freedom.

The Treaty of 1866 called for the Choctaws to free the enslaved Africans in exchange for $300,000 paid by the U.S. government to the Choctaws and the Choctaw Nation. Many of those liberated chose to stay and live as free people among the tribal communities. More than 100 years later, in 1983, Choctaw voters adopted a tribal constitution that declared all members "shall consist of all Choctaw Indians by blood whose names appear on the original rolls of the Choctaw Nation … and their lineal descendants," all but expelling Freedmen citizens from citizenship within tribal communities.

Festivities became more commercialized in the 1920s during the Great Migration

Early Juneteenth celebrations were spent in prayer and with family but eventually expanded to include everything from rodeos and baseball to certain foods like strawberry soda pop and barbecues. Food has long been central to Juneteenth, as participants often arrive with their own dishes.

Attention for Juneteenth waned in the early 20th century as classroom instruction veered away from the history of enslavement in the U.S. and instead taught that slavery ended in one fell swoop with the Emancipation Proclamation.

Juneteenth officially became a Texas state holiday in 1980

Texas was the last Confederate state to free enslaved people from bondage, but it was also the first to make Juneteenth an official state holiday.

The late Texas Rep. Al Edwards put forth a bill in 1979 called HB 1016 that was entered into state law later that year and went into effect on Jan. 1, 1980. It was more than a decade before another state—Florida—passed a similar law of recognition.

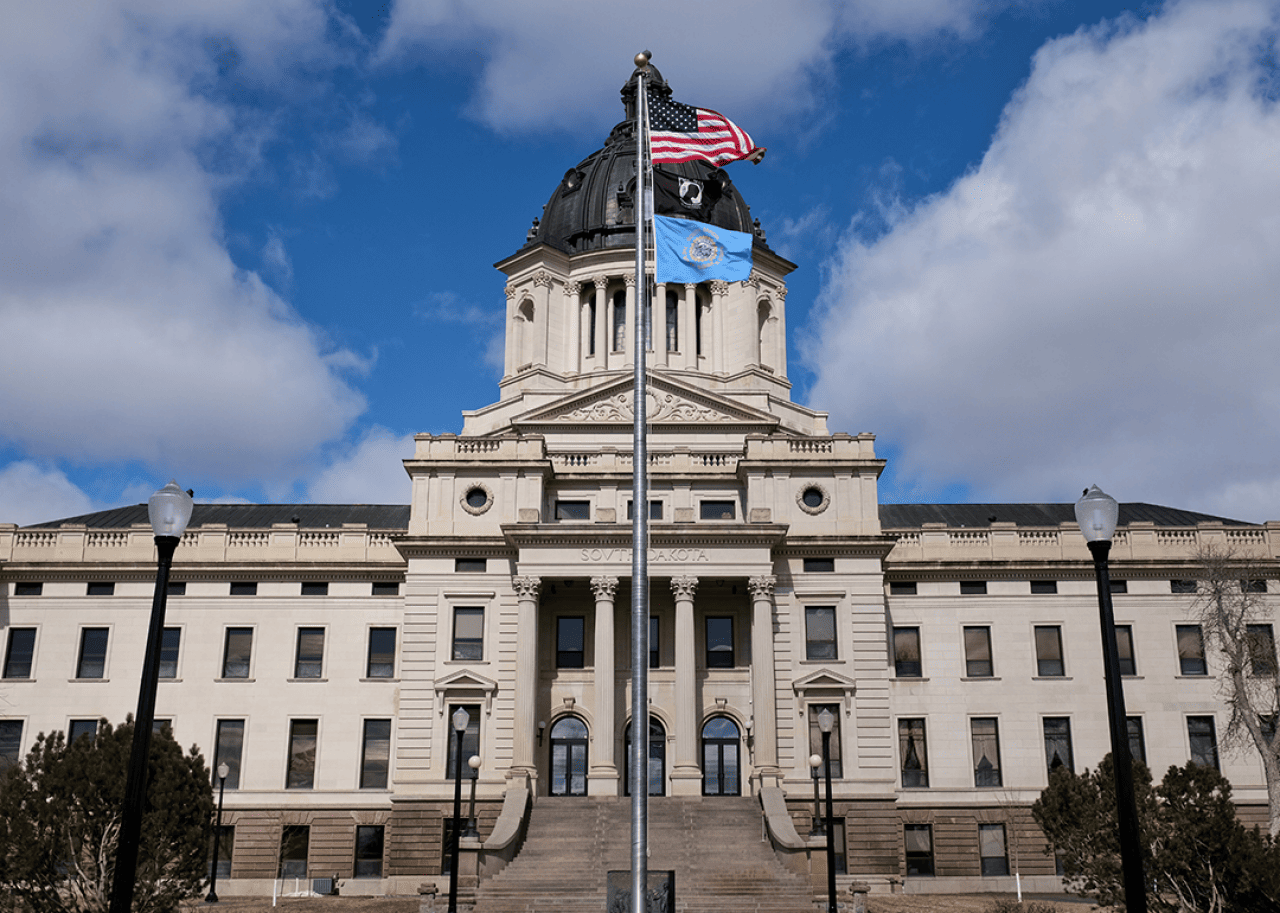

South Dakota was the last state to make Juneteenth a legal holiday

In February 2022, Gov. Kristi Noem signed HB 1025 to recognize Juneteenth as a legal holiday.

Hawai'i and North Dakota preceded South Dakota by about eight and 10 months, respectively.

Juneteenth wasn't recognized as a federal holiday until 2021

Juneteenth achieved increasing recognition in recent decades, but the full embrace of the celebration as a national holiday gained momentum around the nation following the murder of George Floyd on May 20, 2020. The resultant Black Lives Matter protests that erupted worldwide in a stance against acts of racial injustice and police brutality spurred corporations nationwide to support Juneteenth as an act of allyship, and things snowballed from there.

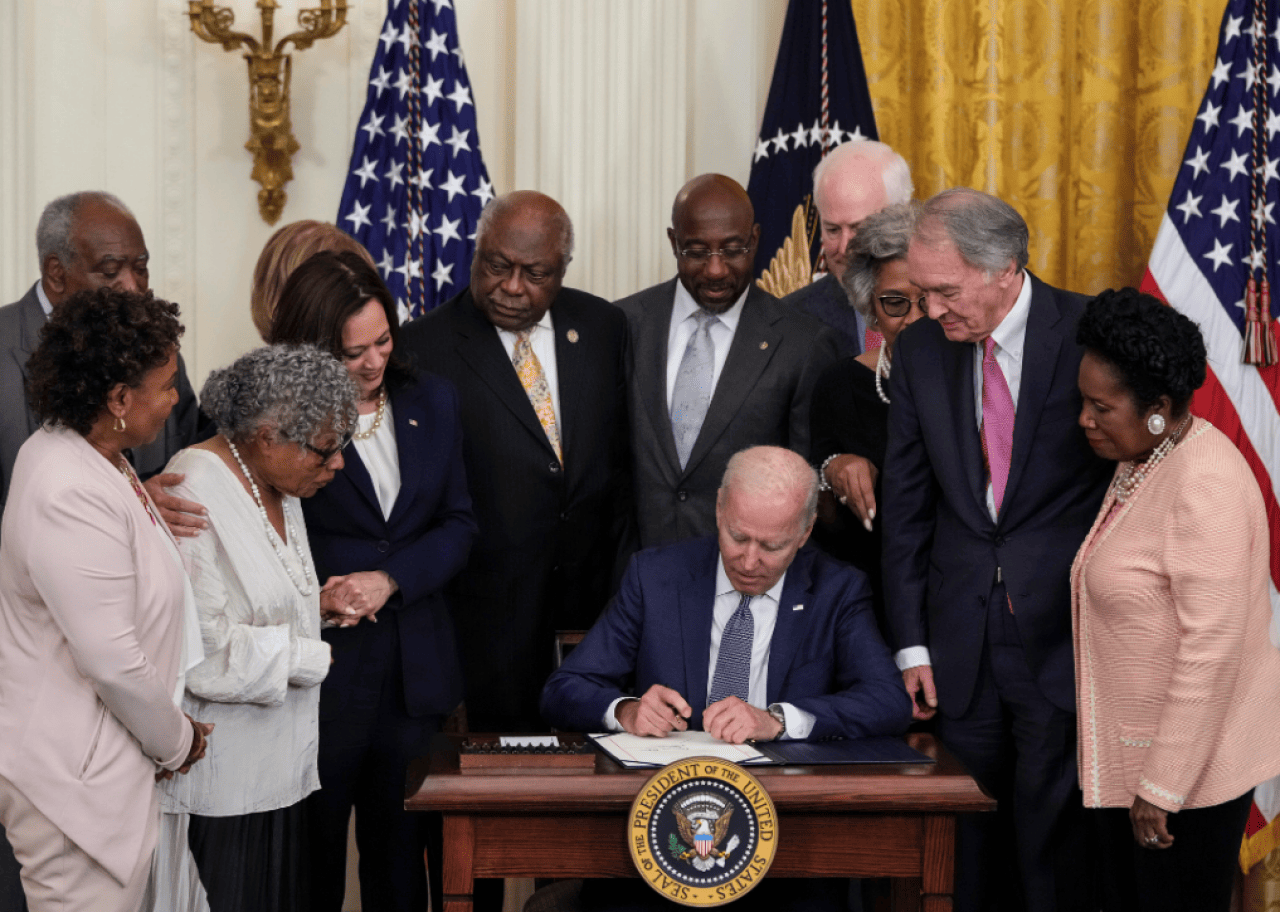

The following year, President Joe Biden signed a bill in June 2021 officially declaring Juneteenth a national holiday. Juneteenth was the first new federal holiday since 1983 (MLK Jr. Day) after decades of organizing.

Additional writing and copy editing by Paris Close.

Juneteenth—also known as Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, or the country’s second Independence Day—stands as an enduring symbol of Black American freedom.

When Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger and fellow federal soldiers arrived in Galveston, a coastal town on Texas’ Galveston Island, on June 19, 1865, it was to issue orders for the emancipation of enslaved people throughout the state.

Although telegraph messages had shared news of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and while the war had been settled in the Union’s favor since April of 1865, Granger’s message was a promise of accountability. There was now a large enough coalition to enforce the end of slavery and overwhelm the Texas Conferedate constitution, which forbade individuals’ release from bondage.

In that way, Texas became the last Confederate state to end slavery in the U.S.

Though celebrated for hundreds of years in parts of the U.S., Juneteenth’s history and significance only recently scaled for a massive national audience and inflection point. The historic date was not recognized as a federal holiday until 2021—more than a century and a half after it took place.

Stacker explored the history and significance of Juneteenth by examining historical documentation including texts for General Order #3 and the Emancipation Proclamation. Stacker also researched the lasting significance of this historic day while clearing up some of the most egregious misinformation about it.

You may also like: History of African Americans in the US military

![]()