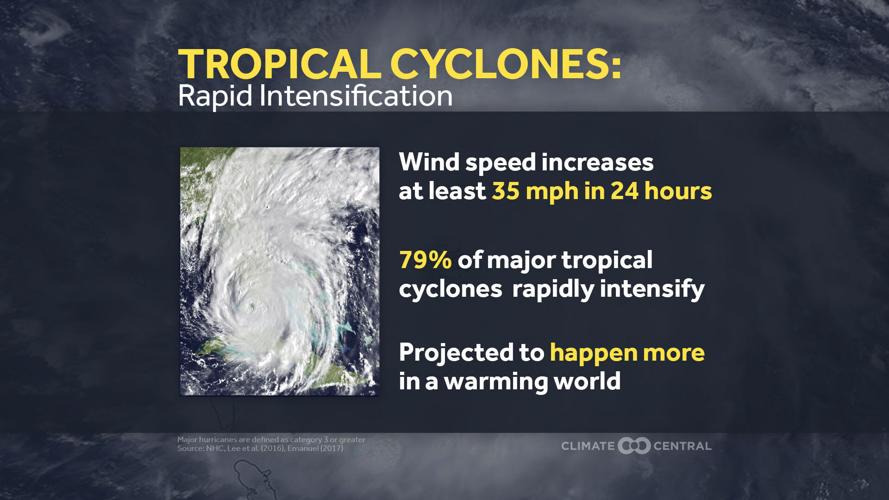

Idalia will remain adrift in the Atlantic Ocean this weekend, but it has already joined a small list of storms that intensified rapidly in the 24 hours before making landfall in the United States.

By convention, rapid intensification is the term given to a tropical system whose strongest sustained winds increase at least 35 mph within 24 hours, and Idalia actually exceeded that rate.

(Climate Central)

In the 24 hours ending 1 a.m. Wednesday, the strongest sustained winds increased from 75 mph to 120 mph. Less than eight hours later, the hurricane made landfall near Keaton Beach, Florida.

With regard to intensification rates, this puts it in the same league as Laura in 2020 and Michael in 2018, each devastating Gulf Coast storms. Humberto from 2007 also sits high on the rapid intensification list, going from a poorly organized tropical depression to a Category 1 hurricane in 24 hours, although it never reached the ferocity of Laura, Michael, or Idalia.

Rapid intensification hinges on two primary criteria, wind shear and ocean water temperature. If the wind aloft is very light in the area where the storm is heading, it is easier for the storm — effectively a massive heat engine — to concentrate its energy into a circular shape. In turn, the warmer water provides the fuel for that heat engine.

Idalia moved into an area of very little wind shear in the 36 hours before landfall, and water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico along the path of the storm were in the upper 80s. As a result, rapid intensification was not a surprise.

And thinking longer term, as the climate continues to warm, rapid intensification of hurricanes will probably become more common. Understanding precisely where Idalia fits within this climate context is tricky, but there are some early takeaways.

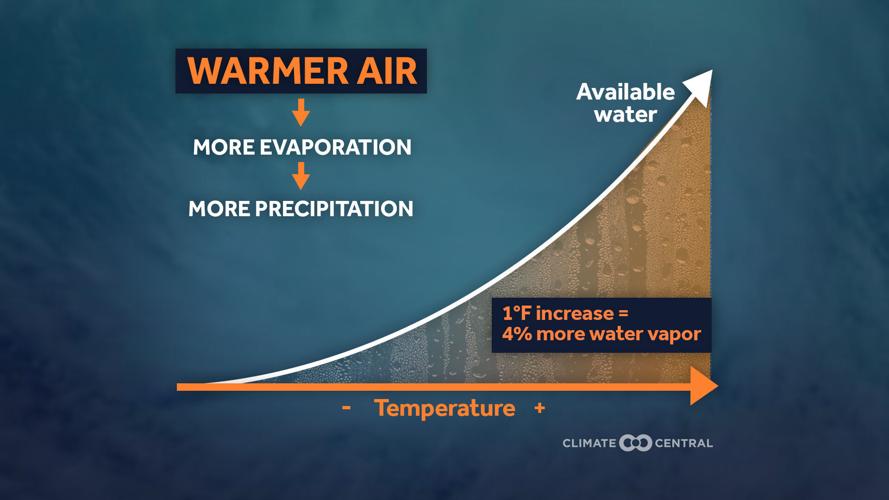

Evaporation goes up rapidly even for small increases in temperature (Climate Central)

To be sure, the Gulf of Mexico is always very warm in late August, which is why it is hurricane prone in the first place. But after some minor ups and downs in its temperature through the middle 20th century, a prolonged warming trend has developed, up about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1970s. On average, this suggests storms can go stronger, and perhaps intensify more rapidly.

How much more rapidly depends on the other environmental conditions at the time, but a 2022 study suggests that rapid intensification is beginning to occur more often — and storms like Idalia will only contribute to the growing body of evidence.

When it comes to wind damage, even an apparently small increase in strength has large impacts at landfall and beyond. This concept is a basic tenet of physics — energy of motion is based on the square of the wind speed. So if the wind speed doubles, the energy is increased by a factor of four.

However, wind damage is only one part of a storm’s impacts, as water does more long-term damage than wind. Storm surge depends on the size of the storm, its speed, orientation of the coastline, and the shape of the land beneath the water. The warming climate plays a role here too. As sea level has risen, storm surge can move farther inland.

Climate scientist Zeke Hausfather explains why oceans are at record-high temperatures on this week's episode of Across the Sky.

Furthermore, the warmer air and water lead to more evaporation into the atmosphere. Not only does this make the storm stronger, it means more water is available to come down as heavy rain. Over time, this raises the risk of flooding in areas away from the coast: streams, creeks, and rivers.

Hurricanes are not expected to become more numerous in the warming climate, but increasing sea level, warmer water, and heavier rain will make them even more impactful when they do come ashore. Considering how much development continues at the nation’s coastlines, we need to be keenly aware of the accelerating risks posed by these massive tropical heat engines.

Are you prepared if a major storm strikes? According to this week's guest, knowledge is power when protecting your home.