After Paola Freites was allowed into the U.S. in 2024, she and her husband settled in Florida, drawn by warm temperatures, a large Latino community and the ease of finding employment and housing.

They were among hundreds of thousands of immigrants who came to the state in recent years as immigration surged under former President Joe Biden.

No state was more affected by the increase in immigrants than Florida, according to internal government data obtained by The Associated Press. Florida had 1,271 migrants who arrived from May 2023 to January 2025 for every 100,000 residents, followed by New York, California, Texas and Illinois.

Paola Freites poses for a portrait Aug. 21 inside the two-bedroom mobile home in Apopka, Fla., where she lives with her husband and three children after fleeing persecution in Colombia.

Freites and her husband fled violence in Colombia with their three children. After months in Mexico they moved to Apopka, an agricultural city near Orlando, where immigrants could find cheaper housing than in Miami as they spread in a community that already had large populations of Mexicans and Puerto Ricans. Her sister-in-law owned a mobile home that they could rent.

“She advised us to come to Orlando because Spanish is spoken here and the weather is good,” Freites, 37, said. “We felt good and welcomed.”

The data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which must verify addresses of everyone who is allowed to enter the U.S. and stay to pursue an immigration case, shows Miami was the most affected metropolitan area in the U.S. with 2,191 new migrants for every 100,000 residents. Orlando ranked 10th with 1,499 new migrants for every 100,000 residents.

The CBP data captured the stated U.S. destinations for 2.5 million migrants who crossed the border, including those like Freites who used the now-defunct CBP One app to make an appointment for entry.

Freites and her husband requested asylum and obtained work permits. She is now a housekeeper at a hotel in Orlando, a tourist destination with more than a dozen theme parks. Her husband works at a plant nursery.

“We came here looking for freedom, to work. We don’t like to be given anything for free,” said Freites, who asked to be identified her by her middle and second last name for fear of her mother’s safety in Colombia.

Hotels and highways are seen Aug. 22 around Universal Volcano Bay water park in Orlando, Fla., which saw an influx of migrants in recent years.

Historically, Central Florida’s immigrant population was mainly from Mexico and Central America, with a handful of Venezuelans coming after socialist Hugo Chávez became president in 1999.

In 2022, more Venezuelans began to arrive, encouraged by a program created by the Biden administration that offered them a temporary legal pathway. That same program was extended later to Haitians and Cubans, and their presence became increasingly visible. The state also has a large Colombian population.

Many immigrants came to Florida because they had friends and relatives.

Businesses catering to newer arrivals opened in shopping areas with Mexican and Puerto Rican shops. Venezuelan restaurants selling empanadas and arepas opened in the same plaza as a Mexican supermarket that offers tacos and enchiladas. Churches began offering more Masses in Spanish and in Creole, which Haitians speak.

As the population increased, apartments, shopping centers, offices and warehouses replaced many of the orange groves and forests that once surrounded Orlando.

Dario Romero, right, co-owner of Venezuelan restaurant TeqaBite, greets a customer Aug. 21 in Kissimmee, Fla.

New immigrants found work in the booming construction industry, as well as in agriculture, transportation, utilities and manufacturing. Many work in restaurants and hotels and as taxi drivers. Some started their own businesses.

“It’s just like a very vibrant community,” said Felipe Sousa-Lazaballet, executive director at Hope CommUnity Center, a group that offers free services to immigrants in Central Florida. “It’s like, ‘I’m going to work hard and I’m going to fight for my American dream,’ that spirit.”

Immigrants’ contributions to Florida’s gross domestic product — all goods and services produced in the state — rose from 24.3% in 2019 to 25.5% in 2023, according to the pro-immigration American Immigration Council’s analysis of the Census Bureau’s annual surveys. The number of immigrants in the workforce increased from 2.8 million to 3.1 million, or 26.5% to 27.4% of the overall population. The figures include immigrants in the U.S. legally and illegally.

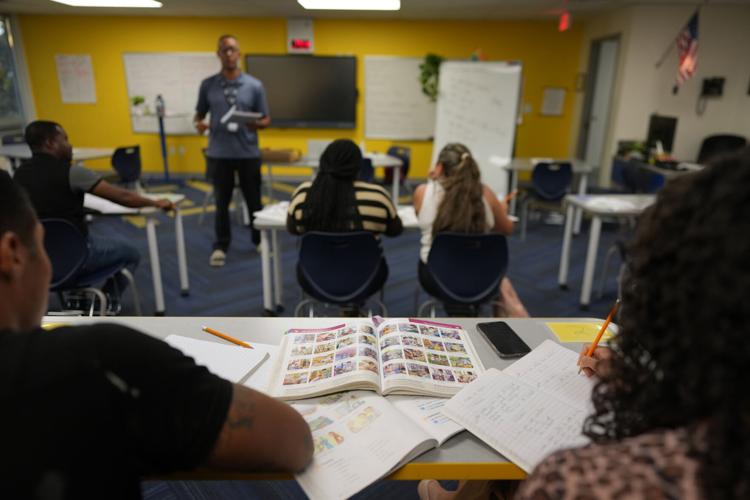

Immigrants trying to learn English take notes Aug. 19 as Eliezer Guerrero of Catholic Charities of Central Florida teaches an ESOL class in Orlando.

Groups that help immigrants also increased in size.

“We got hundreds of calls a week,” said Gisselle Martinez, legal director at the Orlando Center for Justice. “So many calls of people saying ‘I just arrived, I don’t know anybody, I don’t have money yet, I don’t have a job yet. Can you help me?’”

The center created a program to welcome them. It grew from serving 40 people in 2022 to 269 in 2023 and 524 in 2024, Melissa Marantes, the executive director, said.

In 2021, about 500 immigrants attended a Hispanic Federation fair offering free dental, medical and legal services. By 2024, there were 2,500 attendees.

Meanwhile, Hope went from serving 6,000 people in 2019, to more than 20,000 in 2023 and 2024.

Mexican asylum-seeker Blanca's three young children play Aug. 20 inside the family's rented duplex in Apopka, Fla. Blanca is using only her first name because she fears deportation.

After President Donald Trump returned to office in January, anxiety spread through many immigrant communities. Florida, a Republican-led state, worked to help the Trump administration target illegal immigration.

Blanca, 38, a single mother from Mexico who crossed the border with her three children in July 2024, said she came to Central Florida because four nephews who lived in the area told her it was a peaceful place where people speak Spanish. The math teacher, who requested asylum, insisted on being identified by her first name only because she fears deportation.

In July 2025, immigration officials placed an electronic bracelet on her ankle to monitor her.

Because a friend was deported after submitting a work permit request, she did not ask for one herself, she said.

“It’s scary,” she said. “Of course it is.”

An influx of immigrants boosted Orlando's economy but many now fear detention

Luis, 30, who fled Venezuela after being an opposition political activist while at university, poses for a picture Aug. 19, 2025, in the apartment complex where he lives in Orlando, Fla. The aspiring entrepreneur with a degree in mechanical engineering requested asylum in the U.S. and received a work permit which allows him to support himself as an Amazon delivery driver as he goes through the legal asylum process.

Venezuelan asylum seeker Luis, 30, runs through the rain Aug. 19, 2025, as he delivers packages in Winter Park, Fla. Luis, who fled Venezuela after being an opposition political activist as a university student, was granted a long-term work permit that allows him to support himself as an Amazon delivery driver as he goes through the legal asylum process.

Hotels and highways are seen Aug. 22, 2025, around Universal Volcano Bay water park in Orlando, Fla. Migrants who moved to central Florida in recent years say they were drawn by warm temperatures, a large migrant community, and the ease of finding jobs in one of the United States' tourism and hospitality hot spots.

Paola Freites, who asked to be identified by her middle name and second last name to protect her family's safety, poses for a portrait Aug. 21, 2025, inside the two-bedroom mobile home in Apopka, Fla., where she lives with her husband and three children after fleeing persecution in their native Colombia.

Colombian asylum-seeker Paola Freites, 37, who asked to be identified by her middle name and second last name to protect her family's safety, points to scars Aug. 21, 2025, in Apopka, Fla. The scars were left by a brutal gang rape and torture she suffered at age 13, in which her attackers left her for dead after cutting open her abdomen.

Paola Freites, who asked to be identified by her middle name and second last name to protect her family's safety, is reflected Aug. 21, 2025, in a poster of John Wayne, whom her teenaged son is a fan of, inside the two-bedroom mobile home in Apopka, Fla., where she lives with her husband and three children after fleeing persecution in their native Colombia.

Immigrants trying to learn the English language participate in ESOL classes Aug. 19, 2025, offered by Catholic Charities of Central Florida in Orlando.

Patricia Otero writes phrases on the board Aug. 19, 2025, in Orlando as she teaches a Catholic Charities of Central Florida ESOL class to immigrants trying to learn English.

Immigrants trying to learn the English language do a workbook exercise Aug. 19, 2025, in Orlando as they participate in an ESOL class offered by Catholic Charities of Central Florida.

Irrigation sprinklers water rows of flowers and plants Aug. 21, 2025, inside a nursery in Apopka, Fla., where migrants often find work in the agricultural sector.

A worker walks past irrigation sprinklers watering flowers and plants Aug. 21, 2025, in a nursery in Apopka, Fla., where migrants often find work in the agricultural sector.

Dario Romero, right, co-owner of Venezuelan restaurant TeqaBite, greets a customer Aug. 21, 2025, in Kissimmee, Fla. Despite a big increase in the local Venezuelan population in the past several years, Romero says the restaurant recently struggled to fill job openings and business is down. An immigration crackdown under President Donald Trump led to some migrants losing their legal status and work permits, while many others still in legal processes are too fearful to venture out of the house except to go to and from work.

People wait in line Aug. 22, 2025, at a food pantry in Orlando, Fla., that provides assistance to anyone in need, including some migrants who had their legal protections and work permits terminated.

Watermelons are handed out to people waiting in line Aug. 22, 2025, at the food pantry in Orlando, Fla.

A Haitian immigrant braids another woman's hair Aug. 19, 2025, inside an Orlando, Fla., home shared by many members of a Haitian extended family.

Detamisse Janvier, 20, reacts Aug. 22, 2025, in Orlando, Fla., as she talks about the circumstances that led her to flee Haiti and seek asylum in the U.S. Her face still bears a scar from being injured while running desperately to escape an attack by an armed gang on her home in Port-au-Prince.

Blanca, a 38-year-old math teacher from Mexico who crossed the border with her three children in 2024 and applied for asylum, sits at a table Aug. 20, 2025, inside the family's rented two-bedroom duplex in Apopka, Fla.

Blanca washes dishes Aug. 20, 2025, as her three children play in Apopka, Fla.

Two of the young children of Mexican asylum-seeker Blanca hug Aug. 20, 2025, as they play inside the family's rented duplex in Apopka, Fla.

Two of Blanca's young children swing a doll that was given to them by the Catholic church they belong to, as they play Aug. 20, 2025, inside the family's rented duplex in Apopka, Fla.

A theater marquee reads "We Love America" on Aug. 20, 2025, alongside the federal government building that houses the immigration court and the Social Security Administration office in downtown Orlando, Fla.