MINNEAPOLIS — When U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement flooded Minneapolis, Shane Mantz dug his Choctaw Nation citizenship card out of a box on his dresser and slid it into his wallet.

Some strangers mistake the pest-control company manager for Latino, he said, and he fears getting caught up in ICE raids.

Like Mantz, many Native Americans now carry tribal documents proving their U.S. citizenship in case they are stopped or questioned by federal immigration agents.

This is why dozens of the 575 federally recognized Native nations seek to make it easier to get tribal IDs. They waived fees, lowered the age of eligibility — ranging from 5 to 18 nationwide — and now print the cards faster.

It's the first time tribal IDs were widely used as proof of U.S. citizenship and protection against federal law enforcement, said David Wilkins, an expert on Native politics and governance at the University of Richmond. "I don't think there's anything historically comparable," he said. "I find it terribly frustrating and disheartening."

As Native Americans around the country rush to secure documents proving their right to live in the United States, many see a bitter irony.

"As the first people of this land, there's no reason why Native Americans should have their citizenship questioned," said Jaqueline De León, a senior staff attorney with the nonprofit Native American Rights Fund and member of Isleta Pueblo.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security didn't respond to more than four requests for comment over a week.

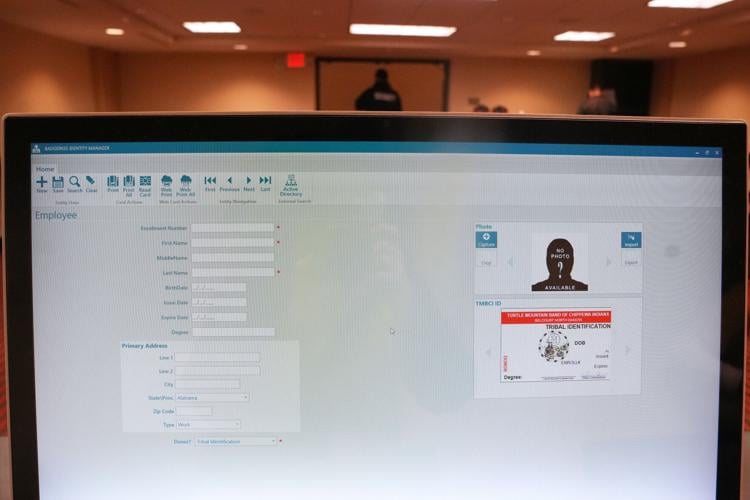

A template of a tribal identification card is displayed on a computer Jan. 23 in Minneapolis.

Native identity in a new age of fear

Since the mid- to late 1800s, the U.S. government kept detailed genealogical records to estimate Native Americans' fraction of "Indian blood" and determine their eligibility for health care, housing, education and other services owed under federal legal responsibilities. Those records also were used to aid federal assimilation efforts and to chip away at tribal sovereignty, communal lands and identity.

Beginning in the late 1960s, many tribal nations began issuing their own forms of identification. In the past two decades, tribal photo ID cards became commonplace and can be used to vote in tribal elections, to prove U.S. work eligibility and for domestic air travel.

About 70% of Native Americans today live in urban areas, including tens of thousands in the Twin Cities, one of the largest urban Native populations in the country.

There, in early January, a top ICE official announced the "largest immigration operation ever." Masked, heavily armed agents traveling in convoys of unmarked SUVs became commonplace in some neighborhoods. More than 3,400 people were arrested, according to ICE. At least 2,000 ICE officers and 1,000 Border Patrol officers were on the ground.

Representatives from at least 10 tribes traveled hundreds of miles to Minneapolis — the birthplace of the American Indian Movement — to accept ID applications from members there. Among them were the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Ojibwe of Wisconsin, the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of South Dakota and the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa of North Dakota.

Faron Houle, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, speaks about applying for a tribal identification card at a Jan. 23 pop-up event in Minneapolis.

Turtle Mountain citizen Faron Houle renewed his tribal ID card and got his young adult son's and his daughter's first ones. "You just get nervous," Houle said. "I think (ICE agents are) more or less racial profiling people, including me."

Events in downtown coffee shops, hotel ballrooms, and at the Minneapolis American Indian Center helped urban tribal citizens connect and share resources, said Christine Yellow Bird, who directs the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation's satellite office in Fargo, North Dakota.

Yellow Bird made four trips to Minneapolis in recent weeks, putting nearly 2,000 miles on her 2017 Chevy Tahoe, to help citizens in the Twin Cities who can't make the long journey to their reservation.

She said she always keeps her tribal ID with her. "I'm proud of who I am," she said. "I never thought I would have to carry it for my own safety."

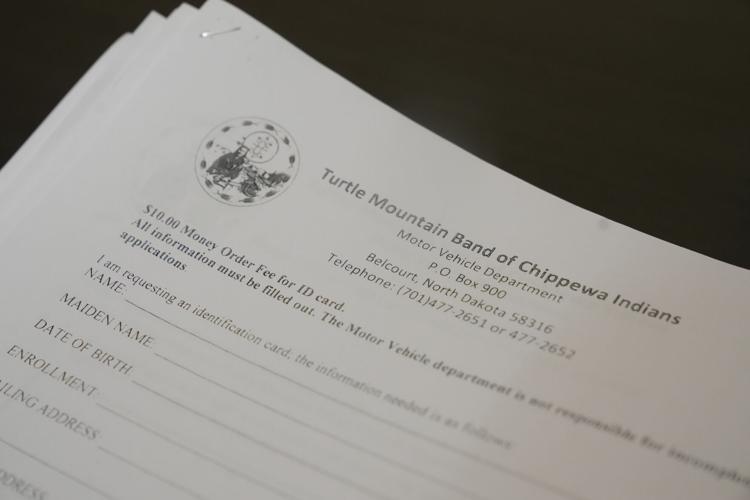

Paperwork to apply for a tribal identification card is displayed Jan. 23 in Minneapolis.

Some Native Americans say ICE is harassing them

Last year, Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren said that several tribal citizens reported being stopped and detained by ICE officers in Arizona and New Mexico. He and other tribal leaders have advised citizens to carry tribal IDs with them at all times.

Last November, Elaine Miles, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon and an actress known for her roles in "Northern Exposure" and "The Last of Us," said she was stopped by ICE officers in Washington state who told her that her tribal ID looked fake.

The Oglala Sioux Tribe banned ICE from its reservation in southwestern South Dakota and northwestern Nebraska, one of the largest in the country.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota said a member was detained in Minnesota.

Peter Yazzie, who is Navajo, said ICE pushed him to the ground and searched his vehicle before arresting and holding him in Phoenix for several hours. "It's an ugly feeling," he said. "It makes you feel less human. To know that people see your features and think so little of you."

DHS did not respond to questions about the arrest.

Places in the United States with Native American meanings

Alaska

Updated

The name Alaska comes from the Aleut tribe and their word “alyeska.” When translated, it means "great land," drawing inspiration from the state’s vast landscapes. The Aleut people originally inhabited western Alaska and the Aleutian Islands and are one of the five major Native Alaskan groups.

Alaska: Wasilla, Sitka

Updated

The growing city of Wasilla paid homage to a Dena’ina Athabascan local chief called Chief Wasilla when choosing a name. Some believe it means “breath of fresh air” in the local dialect, while others debate it is a variation of a Russian name. If you head farther south, you’ll find the city and borough of Sitka, a Tlingit word, which takes the very literal translation of “people on the outside of Baranof Island.”

Arizona

Updated

Although the exact origin is still debated, it is believed that the state name Arizona is based off of the Tohono O’odham word “Al Shon,” which means “small spring” or “place of the small spring.” Today, 4.5% of Arizona's population is Native.

Arkansas

Updated

The state of Arkansas gets its name from the Quapaw tribe and means “people who live downstream.” The French named the countryside in their honor after encountering them in the Mississippi River Valley.

Arkansas: Osceola, Ouachita River

Updated

Located on the Mississippi River, Osceola was named after the Seminole tribe’s Chief Osceola, known for leading the fight against the U.S. government as they attempted to remove the Seminole from their ancestral land. A different tribe, the Washita, influenced the naming of the Ouachita River, whose name means “river of good hunting grounds” for its well-known fishing stock.

California: Malibu, Truckee, Lake Tahoe

Updated

A large number of indigenous people settled along California’s coast. The name Malibu comes from the Chumash people’s word “humaliwo,” meaning “where the surf sounds loudly.” Further north is the city of Truckee, whose name originates from a Paiute Chief who greeted travelers with the phrase “tro-kay,” meaning everything is alright. It was misinterpreted to be his name, and the travelers named the town Truckee in his honor. Close to Truckee is Lake Tahoe, a name deriving from the Washoe word meaning “the lake.”

Connecticut

Updated

Connecticut’s name originates from the Mohegan word “Quinnehtukqut,” which translates to “long river place” or “beside the long tidal river.” This was in reference to the Connecticut River, where the Mohegan tribe had lived for a period of time.

Delaware: Nanticoke River

Updated

The Nanticoke River was named for the Nanticoke people who lived on the river and were accomplished canoeists. Nanticoke translates to “those who ply the tidal stream” or “tidewater people.”

Dakotas

Updated

The Dakota territory, which during the time it was named included both North and South Dakota, was named after the Sioux tribe's word for allies or friends. Although both states were admitted into the Union separately, neither changed the name from Dakota.

North Dakota: Wahpeton, Lake Sakakawea

Updated

The southeastern city of Wahpeton was named for the Wahpeton tribe. The name is a Sioux word meaning “dwellers among the leaves.” The man-made reservoir Lake Sakakawea was named after the woman who most of the country knows as Sacagawea, member of the Shoshone tribe. Her name translates to “bird woman” in the Hidatsa language.

Florida: Miami, Tallahassee, Tampa

Updated

Sitting right on the water of the southeastern tip of Florida, the city of Miami was named after the Tequesta word “mayami,” which translates to big or sweet water. The capital of Florida, Tallahassee also has a name of Native American origin, coming from the Creek word meaning “old town.” And then there’s Tampa on the gulf, whose name comes from the Creek word for “sticks of fire,” in reference to the driftwood often found on the shore used as firewood.

Georgia: Chattahoochee River, Savannah, Kennesaw

Updated

On the border of Georgia flows the Chattahoochee River, which the Creeks named from the words “chat” meaning stone and “ho-che” meaning marked or flowered. On the coast, the city of Savannah was named after the Savannah River, whose name comes from a band of Shawnee natives known as Savana. Closer to Atlanta, the city of Kennesaw got its name from the Cherokee word “gah-nee-sah” meaning burial ground or cemetery.

Idaho: Pocatello, Nampa, Coeur d’Alene

Updated

The largest city in Bannock County, Pocatello is named after the Shoshone leader Pocatello, although the origin of his name is unknown as it is not a Shoshone word. Close to the eastern border of Idaho lies Nampa, a city whose name is a mispronunciation of the Shoshone word “nambe” or “nambuh,” thought to mean moccasin but actually translating to footprints. The city and Lake Coeur d’Alene comes from the Coeur d'Alene tribe whose name was given to them by French trappers and traders and translates to the “heart of the awl” because of their high skills in trading.

Illinois: Chicago, Pontiac

Updated

Sitting on Lake Michigan, the city of Chicago derives its name from the Miami-Illinois word “shikako” or “shikaakwa” and means “skunk place” in reference to the native wild onions that grew there. A bit further south is the city of Pontiac, which was named in order to honor the great Ottawa tribe chief, Chief Pontiac, who unified 18 Native American tribes.

Indiana

Updated

After the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy traded land making up present-day Indiana, the settlers followed the trend of naming land in the style of Bulgaria, land of the Bulgars, and Virginia, land of the Virgin (Queen) by naming it as the land of the Indians.

Indiana: Kokomo, Tippecanoe River

Updated

In the middle of Indiana is the city Kokomo, named for Chief Kokomo, of the Miami natives. However, there is much speculation about who Kokomo really was and his character. Another place the Miami tribe influenced was the Tippecanoe River, whose name derives from the Miami word for buffalo fish (modern-day carp), a species that thrives in the river.

Iowa

Updated

The state name Iowa comes from the Native American tribe of the same name. The Iowa or Ioway tribe resided in Eastern Iowa at one point, and Iowa City, Iowa River, and Iowa County are all named after them. The word Iowa is a French spelling of the word “ayuhwa,” meaning “sleepy ones,” and was given to the tribe by the Dakota Sioux in jest.

Iowa: Des Moines, Ottumwa, Oskaloosa

Updated

Iowa's capital city Des Moines is thought to have gotten its name from the Peoria word “moingona” referencing burial mounds near the banks or from the name of the Trappist Monks (moines de la Trappe) who lived in huts at the mouth of the river. The Des Moines River influences another city’s name, as it runs through the city of Ottumwa, whose name comes from the Algonquian word meaning “rippling waters.” Oskaloosa is a town in Iowa that was named for the Creek princes Ouscaloosa, which means “last of the beautiful.”

Kansas

Updated

The state of Kansas was named after the Kanza or Kaw tribe, meaning “people of the Southwind.” Indigenous tribes native to Kansas include the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kansa, Kiowa, Osage, Pawnee, and Wichita.

Kansas: Topeka, Osage River

Updated

Kansas capital city Topeka is thought to come from a Kaw Word that translates to “a good place to dig potatoes.” In the eastern part of the state, the Osage River is named for the Osage Nation, meaning “people of the middle waters.”

Kentucky

Updated

Kentucky's state name is said to have derived from various Native American languages. The general consensus is that it comes from an Iroquois word “ken-tah-ten,” meaning “meadow place” or “land of tomorrow.”

Kentucky: Paducah

Updated

Located on the southern side of the Ohio River, the city of Paducah was named for the Padoucas Tribe in 1827 by famed explorer William Clark. Clark got it wrong, though—the Padoucas Tribe wasn't living in the area and Clark was actually moving onto land once occupied by the Chickasaw until the Jackson Purchase in 1819 that opened the land up for settlement.

Louisiana: Ponchatoula, Natchitoches, Houma

Updated

The small city of Ponchatoula has a Choctaw name that means falling, hanging, or flowing hair. This was their way of expressing the beauty of the location because of the moss hanging from the trees.

Maryland: Chesapeake Bay, Quantico, Wicomico River

Updated

Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay gets its name from the Algonquian name “Chsepiook,” which translates to “the great shell-fish bay” because of the large amounts of crabs, oysters, and clams found in the waters. The small town of Quantico is named after a Native American word of unknown origin that possibly means dancing or place of dancing, and the river that Quantico lies on, the Wicomico River was named after the Wighcocomoco (Wicomico) people who lived along the river.

Massachusetts

Updated

The Massachusset tribe who lived south of Boston provides the inspiration for Massachusetts’ state name. The word “Massachusett” roughly translates to at or about the Great Hill, based on the tribe’s location in the Blue Hill region.

Massachusetts: Chicopee, Fall River

Updated

The city of Chicopee is located on the Connecticut River, and its name comes from the Algonquian word meaning violent waters, describing the river that runs by it. Another city named from a river in Massachusetts is the city Fall River. Fall River was named after the QueQuechan River (named by the Wampanoag) that is nearby and translates to “falling water or river.”

Michigan: Kalamazoo, Saginaw

Updated

Located in southern Michigan, the city of Kalamazoo comes from a Native American word whose exact origin is still unknown. Some say it means bubbling or boiling water while others say it means “mirage of the reflecting river.” Moving up to central Michigan, the city of Saginaw comes from a Chippewa word meaning land of the Sauks, a tribe that dominated eastern Michigan.

Minnesota: Minnetonka, Minneapolis

Updated

The suburban city of Minnetonka gets its name from the Sioux words “mni tanka” which translates to great water, in reference to Lake Minnetonka. Another “mni” city, Minneapolis is actually a verbal mashup of the Sioux word for water and the Greek word “polis” meaning city. Water city is an appropriate name given the Mississippi River, Minehaha Falls, and 22 lakes are all within the city limits.

Mississippi

Updated

Translating to "great river" or "father of waters," Mississippi’s name is the French version of the Ojibwe name “msi-ziibi.” Many tribes lived throughout the region well into the 1700s, including the Chakchiuma, lbitoupa, Koroa, Ofogoula, Taposa, Tiou, Tunica and Yazoo tribes along the Yazoo River in the Mississippi Delta; the Bayougoula, Houma and Natchez tribes along the lower Mississippi; and the Acolapissa, Biloxi and Pascagoula tribes who lived on the Gulf Coast.

Mississippi: Pascagoula, Pontotoc

Updated

The city of Pascagoula comes from a Choctaw word that means “bread-eater” and Choctaw Native American tribes who have taken on the name are referred to as bread nation. Farther north is the county and small city of Pontotoc, whose name is Chickasaw for “cattail bread-eater” or “land of the hanging graps.”

Missouri

Updated

A Sioux tribe called the Missouris inspired the naming of the state. For a while, the name's translation was thought to mean muddy water, but it actually translates to “the town of the large canoes,” a title influenced by its location along the Missouri River.

Missouri: Tecumseh, Lake Tapawingo

Updated

The small town of Tecumseh in Missouri was named for the famous Shawnee Chief Tecumseh. There are multiple other places across the country named in his honor. Lake Tapawingo, both the name of the lake and city, takes its name from a Native American word that means beautiful water or beautiful place.

Montana: Missoula, Makoshika State Park

Updated

Missoula, a city in western Montana, is believed to have derived its name from the Salish word from Flathead Nation “nmesuletk” meaning icy water—likely a reference to Glacial Lake Missoula. The largest of Montana’s parks, Makoshika State Park, is of Lakota origin, with the phrase “makoshika,” meaning bad land or earth.

Nebraska

Updated

The name for Nebraska comes from the Oto tribe, semi-nomadic people who moved along the Missouri River. Their word “Nebrathaka” means flat water and was the name they gave the Platte River.

Nevada: Winnemucca, Panaca

Updated

Winnemucca, a small city in Nevada, was named after a local Northern Paiute chief. His daughter, Sarah Winnemucca, became a well-known Native American advocate. Another small city, Panaca, was named for the Southern Paiute word “pan-nuk-ker,” meaning “metal,” “money,” or “wealth.” This references the rich ore that was found in the hills nearby.

New Hampshire: Lake Sunapee, Ossipee

Updated

Lake Sunapee’s name comes from the Algonquin word “suna” meaning “goose” and “apee” meaning “lake.” Together they translate to Goose Lake, in reference to the lake being a favorite spot for wild geese. The town of Ossipee gets its name from the Ossipee Nation, one of the 12 tribes of the Algonquian.

New Jersey: Hackensack, Manahawkin, Paramus

Updated

The Lenape tribe inhabited New Jersey long before Europeans arrived, where one tribe called the Achkinheshcky influenced the naming of the city of Hackensack. “Achkinheshcky” translates to the mouth of a river. The town of Manahawkin near the seaboard of New Jersey is named after a Lenape word either meaning land of good corn or fertile land sloping into the water. The borough of Paramus also comes from a Lenape word “peramsepuss,” which means land of the wild turkeys.

New Mexico

Updated

The original name Mexico is the Aztec word meaning “place of Mexitli,” a god of war and storms. The state is home to 23 indigenous tribes: the Navajo Nation, 19 Pueblos, and three Apaches

New Mexico: Taos, Tucumcari

Updated

A town in northern New Mexico’s high desert, Taos was named after the peaceful Taos Pueblo nation who inhabited the area and their towering pueblo structures. Closer to the eastern border, the city of Tucumcari is believed to have derived its name from a Plains tribe term, possibly Comanche, that means lookout point or signal peak. The Tucumcari Mountain was frequently used as a Native American lookout.

North Carolina: Wanchese and Manteo, Lake Mattamuskeet

Updated

Two towns on Roanoke Island, Wanchese and Manteo, are named for two Native American chiefs. Wachese of the Roanoke Native American Tribe and Manteo of the Croatian Tribe both played a large role in establishing Anglo-Indian relations in Roanoke. The largest natural lake in North Carolina, Lake Mattamuskeet was named by the Algonquian tribe and translates to dry dust, referencing the forest they hunted in that once grew where the lake lies

Ohio

Updated

Taking its name from the Ohio River, the state of Ohio has a name that is Iroquois in origin, translating to “great river.” Among the largest tribes in Ohio was the Shawnee, believed to have ancestral ties to For Ancient people dating as far back as the 1600s, even before the Iroquois arrived.

Ohio: Chillicothe, Lake Erie

Updated

The city of Chillicothe comes from the Shawnee word “chalagawtha” meaning “principal place.” Whenever a village was called Chillicothe it was the home to the principal chief and was the capital of the Shawnees until the death of that chief. Heading north, Lake Erie was named after the Native American tribe the Eries, who lived on the lake’s southern shores. “Erie” translates to "cat" or "lake of the cat," which people attribute to the wildcat or panther.

Oklahoma

Updated

A Choctaw Nation Chief was said to have suggested the name Oklahoma during treaty negotiations. The word Oklahoma comes from two Choctaw words “okla” and “homma,” which put together mean “red people.”

Oklahoma: Broken Arrow, Wewoka

Updated

Named after the translation of a Creek word, the city of Broken Arrow was called so by the Creek tribe because they would break branches off of trees to make their arrows instead of cutting them. The city of Wewoka in the middle of Oklahoma comes from a Seminole word meaning “barking water” inspired by the steady rush of water from the nearby falls. On the Arkansas River, the city of Tulsa is actually a contraction of Tullhassee a Creek word for old town.

Oregon: Tillamook, Wallowa Lake, Klamath River

Updated

The coastal city of Tillamook was named after the Tillamook people whose name in Chinook means “the people of the Nekelim.” Wallowa Lake, both a lake and state park, derives its name from the Nez Perce tribe and means “fish trap.” Flowing through Oregon to California, the Klamath River gets its name from the Chinook word “tlamtl,” which means swiftness.

Pennsylvania: Susquehanna River, Punxsutawney, Pocono

Updated

Although the precise origin of Susquehanna River’s name is uncertain, it 's suspected to come from John Smith's interpretation of the local people's name or a corruption of the Susquehannock word “Queischachgekthanne” meaning "the long crooked river." More certainly traced back, the borough of Punxsutawney was named by the Lenape as “ponsutenink” and translates to the “town of the sandflies.” The Pocono mountain, lake, township, and creek in Pennsylvania is a Lenape word as well and means “a stream between mountains.”

Rhode Island: Sakonnet River, Quonochontaug

Updated

In Rhode Island, the Narragansett tribe controlled most of the region up until the arrival of Roger Williams and had significant naming influence across the state. The Sakonnet River, meaning “haunt of the wild black goose,” serves as a saltwater strait just east of Aquidneck Island. Across the state in the southwest, the small village of Quonochontaug (“Quany” for short) derives its its name from “black fish” for the tautog available in the area.

Tennessee

Updated

Despite debate as to what the name Tennesse means, there is agreement on the state name having evolved from Creek and Cherokee words. While some suggest it means meeting place, another popular translation is bends, as in the bend of a river.

Tennessee: Chattanooga, Tullahoma

Updated

The city of Chattanooga along the Tennessee River gets its name from a Creek word meaning “rock rising to a point.” This refers to Lookout Mountain, whose base begins in the city. More centrally located, the city of Tullahoma is believed to have gotten its name from a word in the Choctaw language meaning "red rock" or from a horse who was named for a Choctaw chief.

Texas

Updated

The state of Texas gets its name from the Native American Caddo language and the word “teyhsas,” which means “friends” or “allies.” This translation is incorporated into the state motto of Texas, which is simply “friendship.”

Texas: Waco, Quanah, Wichita Falls

Updated

Waco derives its name from the Hueco, or Waco, a tribe who originally resided in the area. The significantly smaller city of Quanah was named after Chief Quanah Parker, a famed Comanche chief. The northern city of Wichita Falls gets its name from a legend of a Comanche woman testing the river’s depth and describing it as “wichita,” or waist-deep.

Utah

Updated

There are two theories as to how Utah got its name. The first is that the word Utah originates from the Native American tribe Ute, which translates to the people of the mountains. The second is that it originates from the Apche word “yuttahih” meaning one that is higher up.

Utah: Kanab, Oquirrh Mountains

Updated

Just north of the Arizona state line, the city of Kanab gets its name from a Paiute word meaning “place of the willows.” The Oquirrh Mountains, a mountain range running 30 miles north-south, was named after the Goshute word meaning “wooded mountain.”

Vermont: Winooski River, Bomoseen

Updated

Running through northern Vermont, the Winooski River comes from the Abenaki word “winoskik” meaning "wild onion." This was in reference to the wild leeks and onions that were common along the river banks. The name of a state park, town, and lake, Bomoseen is also an Abenaki word for "keeper of the ceremonial fire."

Virginia: Poquoson, Chickahominy River

Updated

Poquoson is the oldest continuously named city in Virginia, named after the Algonquian term that describes a boundary line between two elevated tracks of land. Flowing through the eastern part of Virginia, the Chickahominy River was named for the Chickahominy tribe who lived near the river.

Washington: Seattle, Tacoma, Spokane

Updated

Surrounded by water in the Pacific Northwest, Seattle was named after a Duwamish leader, Chief Si’ahl, who befriended early settlers. Just south of Seattle, the city of Tacoma was named by the Puyallup, a group of Native American fishermen, and their word for white mountain. Heading east, the city Spokane takes its name from the Spokane tribe whose name means "children of the sun" or "sun people."

West Virginia: Wheeling, Kanawha

Updated

The city of Wheeling’s name comes from the Lenape term “wih link” that means “skull” or “place of the head,” a reference to the beheading of a party of settlers. West Virginia’s most populous county, Kanawha County, comes from the Kanawha tribe that once inhabited the area and is debated to mean "new water," "place of white stone," and several other origins.

Wisconsin

Updated

Originally called “Meskonsing” by the Miami tribe, Wisconsin is the English interpretation of the word and means “river running through a red place.” This was in reference to the now Wisconsin River, stretching for 430 miles.

Wisconsin: Mequon, Milwaukee, Oshkosh

Updated

Located on the western shore of Lake Michigan, the city of Milwaukee is believed to get its name from the Potawatomi word “mahn-ah-wauk,” meaning “council grounds.” Just north is the city of Mequon, whose name comes from the Chippewa word “miguan,” which translates to “ladle” in reference to a nearby lake that is similarly shaped. Continuing north, the city of Oshkosh gets its name from the Menominee Nation of Native Americans and one of their leaders, Chief Oshkosh.

Wyoming

Updated

The name for the state of Wyoming is an English misunderstanding of the Lenape word “Chwewamink,” or “by the big river flat.” Lenape, however, are from Pennsylvania. There are five major Wyoming tribes: Arapaho, Cheyenne, Crow, Shoshone, and Ute.

Wyoming: Cheyenne, Shoshone Lake

Updated

Cheyenne, the capital city of Wyoming, was named for the tribe originally called Shey' an' nah' that roamed the area. They belonged to the Algonquian tribe, one of the largest in North America. Within Yellowstone National Park is the Shoshone Lake named after the Shoshone people in the area, believed to be a Sioux expression meaning “grass house people” or “those who camp together in wickiups,” or wigwams.