WASHINGTON — For generations, official American documents meticulously preserved and protected — from the era of quills and parchment to boxes of paper to the cloud, safeguarding snapshots of the government and the nation for posterity.

Now, the Trump administration sought to expand the executive branch’s power to shield from public view key administration initiatives. Officials used apps like Signal that can auto-delete messages containing sensitive information rather than retaining them for record-keeping. They also shook up the National Archives leadership.

To historians and archivists, it points to the possibility that President Donald Trump will leave less for the nation’s historical record than nearly any president before him.

Such an eventuality creates a conundrum: How will experts — and even ordinary Americans — piece together what occurred when those charged with setting aside the artifacts properly documenting history refuse to do so?

President Donald Trump holds a document with notes about Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Maryland resident who was wrongly deported to a prison in El Salvador, as he speaks with reporters April 18 in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington.

How to preserve history?

The Trump administration says it’s the “most transparent in history,” citing the president’s fondness for taking questions from reporters nearly every day.

However, flooding the airwaves, media outlets and the internet with all things Trump isn’t the same as keeping records that document the inner workings of an administration, historians caution.

“He thinks he controls history,” says Timothy Naftali, a presidential historian who was founding director of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California. “He wants to control what Americans ultimately find out about the truth of his administration, and that’s dangerous.”

Trump long refused to release his tax returns though every other major White House candidate and president did so since Jimmy Carter. White House stenographers still record every word Trump utters, but many of their transcriptions languish in the White House press office without authorization for release — meaning no official record of what the president says for weeks, if at all.

“You want to have a record because that’s how you ensure accountability,” said Lindsay Chervinsky, executive director of the George Washington Presidential Library in Mount Vernon, Virginia.

This image, contained in the indictment against then-former President Donald Trump, shows boxes of records stored in a bathroom and shower at Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Fla.

The law mandates maintaining records

The Presidential Records Act of 1978 mandates the preservation, forever, of White House and vice presidential documents and communications. It deems them the property of the U.S. government and directs the National Archives and Records Administration to administer them after a president’s term.

After his first term, rather than turn classified documents over the National Archives, Trump hauled boxes of potentially sensitive documents to his Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago, where they ended piled in his bedroom, a ballroom and even a bathroom and shower. The FBI raided the property to recover them and Trump was charged but the case was later scrapped.

Trudy Huskamp Peterson, who served as acting archivist of the United States from 1993 to 1995, said keeping such records for the public is important because “decision-making always involves conflicting views, and it’s really important to get that internal documentation to see what the arguments were.”

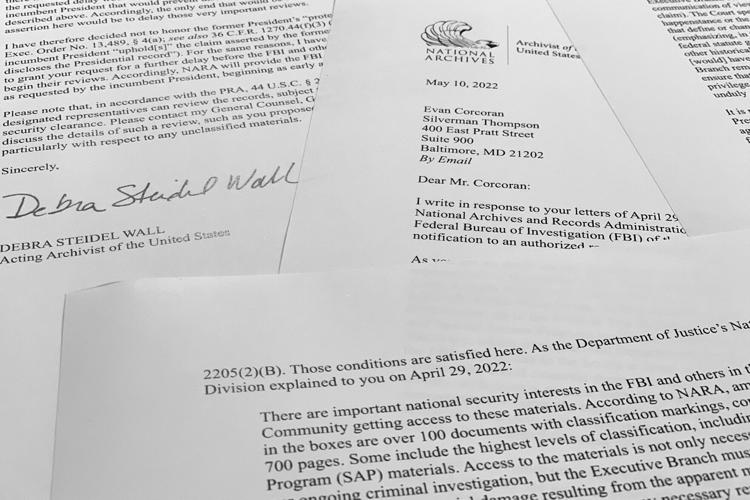

A letter from acting archivist of the United States Debra Steidel Wall to former President Donald Trump's legal team is photographed, Aug. 23, 2022, detailing that the National Archives recovered 100 documents bearing classified markings from 15 boxes retrieved from Mar-a-Lago.

Presidential clashes with archivists predate Trump

President George H.W. Bush’s administration destroyed some informal notes, visitor logs and emails.

After President Bill Clinton left office, his former national security adviser, Sandy Berger, pleaded guilty to taking copies of a document about terrorist threats from the National Archives.

President George W. Bush’s administration disabled automatic archiving for some official emails, encouraged some staffers to use private email accounts outside their work addresses and lost 22 million emails that were supposed to have been archived, though they were uncovered in 2009.

Congress updated the Presidential Records Act in 2014 to encompass electronic messaging — including commercial email services known to be used by government employees to conduct official business.

Back then, use of auto-delete apps like Signal was far less common.

“It’s far easier to copy — or forward — a commercial email to a dot-gov address to be preserved, than it is to screenshot a series of messages on an app like Signal,” said Jason R. Baron, a professor at the University of Maryland and former director of litigation at the National Archives.

Relying on ’an honor system’

There were efforts during the first Trump administration to safeguard transparency, including a memo issued through the Office of White House counsel Don McGahn in February 2017 that reminded White House personnel of the necessity to preserve and maintain presidential records.

The White House points to recently ordered declassification of historical files, including records related to the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, his brother Robert and Martin Luther King Jr.

The Trump administration says it also ended a Biden policy that allowed staffers to use Microsoft Teams, where chats weren’t captured by White House systems. The Biden administration had more than 800 users on Teams, meaning an unknown number of presidential records might have been lost, the Trump administration says.

The White House did not answer questions about the possibly of drafting a new memo on record retention like McGahn’s from 2017.

Chervinsky, author of "The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution," said Congress, the courts and even the public often don’t have the bandwidth to ensure records retention laws are enforced, meaning, “A lot of it is still, I think, an honor system.”

“There aren’t that many people who are practicing oversight,” she said. “So, a lot of it does require people acting in good faith and using the operating systems that they’re supposed to use, and using the filing systems they’re supposed to use.”

Angered by the role the National Archives played in his documents case,Trump fired the ostensibly independent agency’s head, Archivist of the United States Colleen Shogan, and named Secretary of State Marco Rubio as her acting replacement.

Peterson, the former acting national archivist, said she still believes key information about the Trump administration eventually will emerge, but “I don’t know how soon.”

“Ultimately things come out,” she said. “That’s just the way the world works.”

Our emails, ourselves: What the history of email reveals about us

Our emails, ourselves: What the history of email reveals about us

Updated

save_the_drama_for_your_mama@hotmail.com

magically_delicious_vic@hotmail.com

Gen Xers and millennials, in particular, have many embarrassing email addresses hidden in their digital closets. Still, it seemed like a good idea at the time. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the emergence of webmail services like Hotmail, Yahoo Mail, and AOL Mail fostered the unfettered creativity of a young generation that had yet to understand how technology would play into the rest of their lives. Email today permeates every aspect of our digitally driven society, from silly chain messages and professional correspondence to shopping promotions and malicious junk. To trace email's ascension to mainstream use, Spokeo explored news coverage and cultural milestones to chart the evolution of email addresses and how they both shape and reflect our personalities.

Email technology began in the very practical halls of the United States government. It was part of a system established by the Department of Defense in the late 1960s. The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network connected computer users through a shared network rather than through dedicated and exclusive lines.

Government agencies and universities nationwide utilized ARPANET, and in 1971, computer engineer Ray Tomlinson sent the first test network email through ARPANET, using the underused @ symbol to separate the user's and host's names. Tomlinson did not remember his first messages or precisely which dates he sent them, saying that the content was "insignificant and [forgettable]."

ARPANET provided the foundations for what we now know as the internet, where significant and insignificant messages are exchanged every minute of every day. In the years following the birth of email, the technology further developed and eventually became more accessible. Simple Mail Transfer Protocol, the networking standard for emails still used today, was built on concepts from ARPANET introduced in 1982. By 1988, Microsoft had released the first commercially available email client, Microsoft Mail.

Email in the wild: Beyond government and academia

Updated

In the 1990s, email use grew beyond universities and government agencies and into the public as the internet became widely available, and an increasing number of email clients (like Hotmail, Yahoo, and AOL mentioned above) emerged. By 1997, there were already 10 million users worldwide that had a free email account. Internet service providers gave households access to the World Wide Web through dial-up connections, requiring phone lines to work. Who of a certain age could ever forget the high-pitched, off-putting, chaotic melody that signaled the start of a successful connection?

The internet became addicting, with family members regularly checking their emails, shopping, or talking in chat rooms, which could lead to household disputes over online usage and connection speeds. With these new types of personal online interactions, users became a lot more creative with how they identified themselves online, crafting pseudonyms and screen names instead of using their legal names as you would for a business email address.

As internet use became widespread, email caught on as a tool for communication, not just for personal use but also for business purposes. Email quickly became a cost-effective method for business functions like scheduling and validating shipments and transactions. Checking inboxes and composing and sending emails became a major component of the workday, and businesses soon developed practices for professional communication—from how to structure messages to when to divide time between work and personal messages.

An onslaught of messages in living color

Updated

The advent of HTML, or Hypertext Markup Language, helped spur the advancement of the internet and email as tools. HTML, the basic language of web content, helped add some color (quite literally) to emails, especially as businesses began using the technology for marketing purposes. Graphics, custom fonts, video, and other elements kept messages engaging for readers.

But some groups and individuals eventually found email technology troublesome—and quite annoying. As early as 1978, a marketing manager named Gary Thuerk sent a promotional message to about 400 users in ARPANET to promote a new computer product. While considered the first unsolicited "spam" message in history, it reportedly led to over $13 million in sales for his computer company.

As digital advertising and email marketing became prevalent in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with marketers tracking user data, governments began to regulate email and define several guidelines for using the medium. Enacted in 2003, the CAN-SPAM Act in the U.S. required companies to reduce unsolicited email efforts from companies, with measures demanding businesses give members clear ways to unsubscribe.

Before the rise of viral content and memes, information—usually dubious content and outright scams—would spread en masse to users through chain letters, encouraging readers to forward it to as many people as possible. Instant messaging services like AOL Instant Messenger, Internet Relay Chat, and Yahoo Messenger predated social media in connecting people globally, leading to new types of online interactions.

With all these new communication formats came new ways to identify oneself, usually with a pseudonym as a username—especially with the need to keep one's real name private. Some screen names could be based on childhood interests, such as poptardis@gmail.com for one Pop-Tarts lover and (faux) "Doctor Who" fan. Many internet users came up with silly and sometimes regrettable pseudonyms for their email addresses, chat room names, or online gaming monikers, full of random numbers, characters, and pop culture references.

Society became accustomed to email and the internet as an informal means of everyday communication for work or frivolities, something to be taken for granted. However, as the 21st century progressed, the impact of technology on civilization became more evident.

Email on call, available 24/7

Updated

In 2004, Google launched its email client, appropriately titled Gmail. With a desire to provide a better web interface for email, help users sort through spam and promotions, and give them more storage space, Gmail eventually became one of the most popular email services, with about a third of the market share by 2024.

With signature features like its social and promotions folders for inboxes, which automatically categorize the sometimes overwhelming number of emails received, Gmail ranks with other services like Apple Mail and Yahoo Mail as the most used email service today.

As of 2023, there are 4.37 billion email users worldwide, a figure expected to grow to 4.89 billion by 2027. In 2023, about 347 billion emails were sent and received every day globally. Formats like the email newsletter, which collects and aggregates information like news and other niche topics for audiences to digest, continued to evolve.

Another way emails have become more compact for consumers is by fitting email services onto mobile devices such as smartphones. Since BlackBerry disrupted the phone industry with devices that could be used to make phone calls, receive text messages, and check emails, a "mobile work era" commenced, and smartphones became essential for businesses. This trend only continued after the iPhone came onto the scene in 2007. Email formats soon evolved to suit smaller handheld screens.

Texting on phones has become one of the dominant forms of electronic communication, and direct messaging applications like the business-focused Slack and the personal service Facebook Messenger have grown in popularity. Even though these applications have similar functions, email has remained a prominent form of communication for businesses and personal use. It is a great leveler for digital communication. Not everyone may have a Slack account or habitually check Messenger, but they would more likely have an email address.

The use of emails for work, leisure, and marketing continues in the age of social media, artificial intelligence, and an influx of applications. Emails are becoming automated, with personalized marketing content based on customer actions such as signing up for a service or purchasing a product. Customer data tied to email addresses, too, are becoming a commodity, sliced, diced, and scrutinized to gain ground on a corporate target. Even as companies seek data from consumers, users are becoming more wary of sharing their email addresses with organizations, keeping their inboxes clean of clutter in a time where information comes at us from every direction.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Spokeo and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.