WASHINGTON (AP) — A week ago, President Donald Trump was diagnosed with the coronavirus, spent several days at Walter Reed Medical Center for treatment and evaluation, and has since returned to the White House.

Throughout it all, Trump remained in control. He chose not to invoke the 25th Amendment, which details how presidential power can be transferred, either temporarily or more permanently, in the event a president is unable to do the job.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi cited the amendment Friday when introducing legislation to establish a commission that would help determine whether future presidents are capable of maintaining power during an illness. She said it wasn't about whether Trump was capable, but rather that his illness had shown the need to strengthen "guardrails in the Constitution to ensure stability and continuity of government in times of crisis."

Some questions and answers about the 25th Amendment:

AP Explains: Transfer of power under 25th Amendment

WHY WAS IT PASSED?

UpdatedThe push for an amendment detailing presidential succession plans in the event of a president's disability or death followed the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963. President Lyndon B. Johnson in his 1965 State of the Union promised to "propose laws to insure the necessary continuity of leadership should the President become disabled or die." The amendment was passed by Congress that year and ultimately ratified in 1967.

HAS IT BEEN INVOKED TO TRANSFER POWER BEFORE?

UpdatedYes, presidents have temporarily relinquished power but not all invoked the 25th Amendment. Previous transfers of power have generally been brief and happened when the president was undergoing a medical procedure.

In 2002, President George W. Bush became the first to use the amendment's Section 3 to temporarily transfer power to Vice President Dick Cheney while Bush was anesthetized for a colonoscopy. Bush temporarily transferred power in 2007 to undergo another colonoscopy.

The helicopter that will carry President Donald Trump to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., lands on the South Lawn of White House in Washington, Friday, Oct. 2, 2020. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

WHAT ABOUT RONALD REAGAN?

UpdatedThe 25th Amendment was never invoked after President Ronald Reagan was shot in 1981. Reagan did temporarily transfer power to Vice President George H. W. Bush while undergoing surgery to remove a polyp from his colon in 1985, but he said at the time he wasn't formally invoking the 25th Amendment. While he said he was "mindful" of it, he didn't believe "that the drafters of this Amendment intended its application to situations such as the instant one." Bush was acting president for eight hours according to a book on the amendment by John D. Feerick.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

UpdatedTo temporarily transfer power to the vice president, a president sends a letter to the speaker of the House of Representatives and president pro tempore of the Senate stating he is "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office." The vice president then becomes acting president. When the president is ready to resume authority, the president sends another letter. That's spelled out in the amendment's Section 3.

The next section of the amendment, Section 4, lays out what happens if the president becomes unable to discharge his duties but doesn't transfer power. In that case, the vice president and majority of the Cabinet can declare the president unfit. They'd then send a letter to the speaker and president pro tempore saying so. The vice president then becomes acting president.

If the president ultimately becomes ready to resume his duties, the president can send a letter saying so. But if the vice president and majority of the Cabinet disagree, they can send their own letter to Congress within four days. Congress would then have to vote. The president resumes his duties unless both houses of Congress by a two-thirds vote say he's not ready. The section has never been invoked.

A police officer blocks a road before President Donald Trump arrives at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, in Bethesda, Md., Friday, Oct. 2, 2020, after he tested positive for COVID-19. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

WHAT IS BEING PROPOSED NOW?

UpdatedSection 4 of the amendment gives Congress the power to establish a "body" that can, with the support of the vice president, declare that the president is unable to do his job. If they agree the president is unfit, the vice president would take over. But Congress has never set up the body.

On Friday, Pelosi and Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., a former constitutional law professor, proposed the creation of a commission to fill that role. The legislation would set up a 16-member bipartisan commission chosen by House and Senate leaders. It would include four physicians, four psychiatrists and eight retired statespersons, such as former presidents, vice presidents and secretaries of state. Those members would then select a 17th member to act as a chair.

After the commission is in place, Congress would be able to pass a resolution requiring the members to examine the president, determine whether the president is incapacitated and report back. Raskin introduced a similar bill in 2017.

Other election updates:

8 commonly asked questions in the 2020 presidential election

8 commonly asked questions in the 2020 presidential election

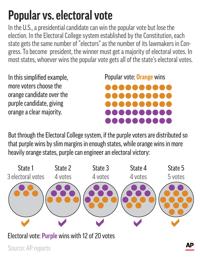

Why can one candidate win the popular vote but another wins the electoral vote and thus the presidency?

UpdatedWhy can one candidate win the popular vote but another wins the electoral vote and thus the presidency?

Answer: That's how the framers of the Constitution set it up.

This unique system of electing presidents is a big reason why Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016. Four candidates in history have won a majority of the popular vote only to be denied the presidency by the Electoral College.

The Electoral College was devised at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. It was a compromise between those who wanted direct popular elections for president and those who preferred to have Congress decide. At a time of little national identity and competition among the states, there were concerns that people would favor their regional candidates and that big states with denser populations would dominate the vote.

The Electoral College has 538 members, with the number allocated to each state based on how many representatives it has in the House plus its two senators. (The District of Columbia gets three, despite the fact that the home to Congress has no vote in Congress.)

To be elected president, the winner must get at least half plus one — or 270 electoral votes.

This hybrid system means that more weight is given to a single vote in a small state than the vote of someone in a large state, leading to outcomes at times that have been at odds with the popular vote.

In fact, part of a presidential candidate's campaign strategy is drawing a map of states the candidate can and must win to gather 270 electoral votes.

In 2016, for instance, Democrat Hillary Clinton received nearly 2.9 million more votes than Trump in the presidential election, after racking up more lopsided wins in big states like New York and California. But she lost the presidency due to Trump's winning margin in the Electoral College, which came after he pulled out narrow victories in less populated Midwestern states like Michigan and Wisconsin.

It would take a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College — an unlikely move because of how difficult it is to pass and ratify constitutional changes. But there's a separate movement that calls for a compact of states to allocate all their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner, regardless of how those individual states opted in an election. That still faces an uphill climb, though.

Is it possible we won't have a president by Inauguration Day?

UpdatedIs it possible we won't have a president by Inauguration Day: Jan. 20, 2021?

Answer: Even if the election is messy and contested in court, the country will have a president on Inauguration Day. The Constitution and federal law ensure it. Here's what happens after voters go to the polls on Nov. 3:

First, states have more than a month to count ballots, including the expected surge of mail-in ballots, and conduct recounts if necessary. But states' electoral votes have to be cast on Dec. 14.

Courts will be mindful of that in refereeing any disputes. During the 2000 election, the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ended Florida's vote recount, saying time had run out before electors were set to meet.

When the electors meet, the candidate who gets at least 270 of the 538 electoral votes wins. But what happens if election issues still prevent a winner from being named? The Constitution has an answer.

The 12th Amendment says that in that case, the House of Representatives elects the president and the Senate elects the vice president. The new Congress that enters in January is the one tasked with carrying out the so-called "contingent election." The president has only been selected this way once, in 1825. The winner was John Quincy Adams.

In a contingent election, House members have to choose among the three people with the most electoral votes. Each state delegation gets one vote, and 26 votes are required to win. In the Senate, the choice is between the top two electoral vote-getters and each senator gets a vote, with 51 votes required to win.

What if that fails and the House hasn't elected a president by Inauguration Day? Then the 20th Amendment takes over. It says the vice president-elect acts as president until a president is picked. And if there's no vice president selected by Inauguration Day?

Well, then the Presidential Succession Act applies.

It says that the speaker of the House of Representatives, the Senate president or a Cabinet officer, in that order, would act as president until there's a president or vice president.

What is the federal government role in elections?

UpdatedWhat is the role of the federal government in elections?

Answer: The federal government has very little role in the elections that choose who is going to run it. Elections are run at the local level and supervised by states. The federal government can help fund elections and set certain standards – such as the requirement that people can register to vote when getting drivers' licenses – through federal law. And of course Washington, D.C. plays a big role in monitoring foreign actors to make sure they don't interfere in elections. But the actual machinery of democracy is run at the state and local level.

States devise the rules of their own elections. Some send everyone a ballot through the mail, others only allow people over age 65 to use that method of voting. The administering of the polls, printing of the ballots and counting of the vote usually occurs on the county level. The state tabulates the counties' totals and declares winners of statewide races, including the presidential contest, and assigns presidential electors accordingly.

The federal government can monitor and ensure that all candidates for federal office are reporting their campaign contributions and expenditures publicly, as required under federal law. It can act to ensure that voters are not deprived of their civil rights. It has in the past sent money to help local elections offices, including $400 million in the CARES Act in March to help with shifts in voting during the pandemic. But the federal government has no role in the operation of polling places or the counting of ballots.

Are voting systems protected from foreign medding?

UpdatedChanges in U.S. election election system security since 2016;

What steps have been taken to protect the nation's election systems from potential interference by foreign powers like Russia? Have voting systems been "hardened" in any way?

Answer: Federal, state and local officials prioritized securing voting systems after Russia interfered in the 2016 election, breaking down bureaucracy to improve communication of potential threats, conducting security reviews and installing network sentinels to detect known cyberthreats and suspicious activity.

A key step was the January 2017 decision by the outgoing Obama administration to designate the election systems as "critical infrastructure" on par with nuclear reactors, banks and the electrical grid. The Department of Homeland Security and its cybersecurity agency have since worked to build relationships with election officials, giving top state election officials security clearances so they can quickly receive sensitive threat intelligence.

After the 2016 interference, state election officials complained that they were not alerted until nearly a year later that Russians had conducted extensive scanning of election systems, specifically targeting voter registration systems.

Communication is vastly improved heading into November, though the threat is unchanged. U.S. intelligence chiefs continue to warn Russia, China and others could interfere in the presidential election beyond so-called "information operations." There is been no indication as yet of any cyber-related attacks directed at election systems.

One of the most feared threats is a well-timed ransomware attack that could scramble or impede access to voter registration data. State election officials have been working to build redundancies into their systems so they can recover quickly in the event of an attack.

Beyond providing comprehensive security assessments, federal officials also offer routine scanning for vulnerabilities and training around best practices. While experts say improvements have been made, they are most concerned about smaller election offices with limited IT and cybersecurity budgets.

Layers of security, including firewalls, threat-detection sensors and multi-factor authentication protocols, have been added to protect voter registration systems. Federal officials noted this summer, however, that adoption of best practices in some places was lagging and it was taking longer in some cases to fix problems identified in federal security reviews.

What's the difference between absentee voting and mail voting?

UpdatedQuestion: What's the difference between absentee voting and mail voting?

Answer: There really isn't any difference. Both refer to the practice of filling out ballots that are sent to voters through the mail and returned either that way or at drop boxes or other designated places.

President Donald Trump has tried to confuse the two terms by claiming that absentee balloting is fine, while mail balloting is not. Absentee voting, the president sometimes argues, means someone has to request a ballot as opposed to automatically getting one in the mail, which he calls mail voting.

The problem is that some states call ballots that people request through the mail "mail ballots." Others call them absentee ballots. Both versions of ballots are processed and counted the same way. The two terms are used interchangeably with no legal distinction. The Trump campaign acknowledged this in a filing in a lawsuit it filed over Pennsylvania's voting procedures.

There is one system that stands out, what is known as universal mail voting. That's when all the state's registered voters receive a ballot through the mail. Prior to this election, five states used this system. Four more have adopted it for November, and Trump has been particularly critical of it.

When are early votes counted?

UpdatedWhat states vote early and when are these votes counted?

Answer: All states allow some form of early voting, be it by casting votes in person at polling places, voting by mail, or both. But each state has its own rules and timelines on when this occurs. Some started in September. Some don't start until mid-October, or even closer to Election Day on Nov. 3.

Just as there are 50 different timelines for early voting, there are 50 different ones for how the votes are counted. Some states allow the "processing" of mail-in ballots — the often time-consuming flattening and opening of envelopes, verifying signatures and sorting ballots into the correct piles for tabulation — to begin as many as three weeks before Election Day. Some only allow it to begin on Election Day itself, which can lead to a chaotic and lengthy count.

That's the process in several key swing states. Democrats fear this will delay the count of mail-in ballots, expected to heavily favor Democrats, and give President Donald Trump a phony early lead that he could seize on to declare the election over.

Mail-in fix

UpdatedQuestion: If a ballot is tossed because of some issue — maybe a missing signature or it got damaged — will the voter be notified that the ballot's been invalidated? And can the voter cast a new ballot?

Answer: This is a tough one — because the rules vary from state to state. The National Conference of State Legislatures has a state-by-state rundown, but that list isn't comprehensive so voters should check with their local elections officials to understand their options.

Voter advocacy groups worry that those unaccustomed to voting by mail will make some kind of error that could invalidate their vote. A study by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission estimates that 1% of mail-in ballots were rejected in the 2016 presidential election. Experts say the main reason was because ballots did not arrive in time.

States that allow so-called "ballot curing" require elections officials to notify voters when something's wrong with a ballot, such as a missing signature or if their signature doesn't match the one on file. The voter will be given a chance to correct it.

Other states have adopted temporary rules on voting by mail — or absentee voting — because of the high interest spawned by the coronavirus pandemic.

Depending on the state, the voter could be notified by mail, email or phone. The deadlines for officials to notify voters again varies by state, and so does the time that a voter has to correct the discrepancy.

Some states allow voters to track their absentee ballots.

The easiest way to cure a ballot, of course, is an ounce of prevention: read voting instructions carefully and double-check that the proper signatures are in place. If you registered when renewing your driver's license, be sure your signature resembles the one on it.

What are the rules around poll watching?

UpdatedWhat are the rules around poll watching on Election Day in the United States?

Answer: President Donald Trump has been urging his supporters to go the polls and "watch very carefully," raising concerns about possible voter intimidation.

Monitoring the votes at polling places is allowed in most states, but rules vary and it's not a free-for-all. States have established rules, in part, to avoid any hint that observers will harass or intimidate voters. There is a long history of whites intimidating and preventing Blacks from voting in the South. And the Republican Party had been prohibited from employing poll monitors until recently because of its own history of using them as a strategy for intimidation.

Generally, the terms poll watchers, poll monitors and citizen observers are interchangeable, and they can be partisan or nonpartisan. Nonpartisan poll watchers are trained to monitor polling places and local elections offices that tally the votes, looking for irregularities or ways to improve the system. Partisan poll watchers are those who favor particular parties, candidates or ballot propositions and monitor voting places and local election offices to ensure fairness to their candidates or causes. They can make note of potential problems as a way to challenge the voting or tabulating process. In all cases, poll watchers are not allowed to interfere with the conduct of the election. In some states, they are allowed to challenge individuals' eligibility to vote; in those cases, a voter may need to file a provisional ballot.

State rules vary on who can be a poll watcher, how many are allowed at polling places or local elections offices, and how they must conduct themselves inside the office or precinct. In most states, political parties, candidates and ballot issue committees can appoint poll watchers, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. They are usually required to be registered voters, but states differ on whether the poll watcher must be registered in the county or precinct rather than just in the state.

This fall's election will be the first in nearly 40 years in which the Republican National Committee will be out from under a consent decree that restricted its ability to engage in coordinated poll watching activities. Democrats are concerned that could open the door for Republicans to engage in the same kind of voter intimidation that resulted in the consent decree in the first place in the early 1980s.