Research suggests that mountain forests with their complex terrain are better at storing carbon dioxide and providing water to humans than flatland forests, both of which have implications for land-use policy makers.

Tyson Swetnam, a scientific analyst at CyVerse, led the study. CyVerse, which is a project funded by the National Science Foundation and led by the University of Arizona, designs computer infrastructure for life-sciences research and trains scientists how to use it to compute large amounts of complex data.

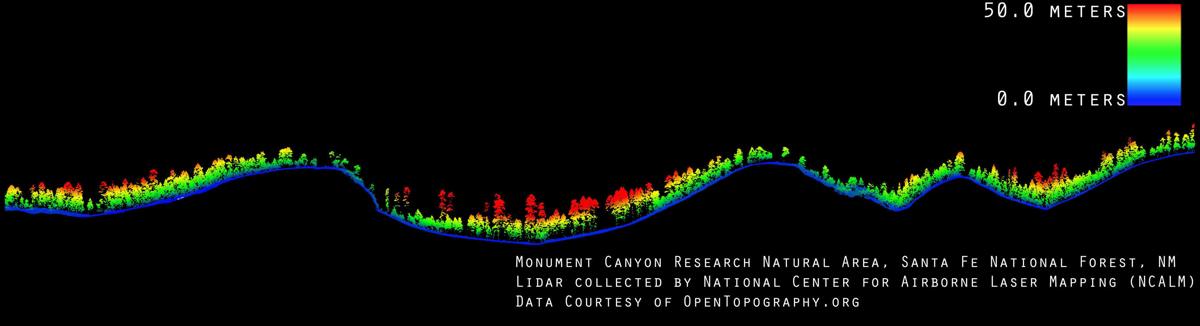

Swetnam collected data from reflected light pulses off the surface of the earth to map the height of the trees and elevation. While looking through cross sections of this 3-D map, he noticed an interesting pattern.

A new idea sprouts

The trees on the valley floors were much taller and fuller than the trees on steep slopes and mountaintops, or as an ecologist would say, they had more biomass. The more biomass a tree has, the more carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas — it has expunged from the air.

“When we first saw the picture ... it was like, ‘Oh my goodness, this is so much greater than we thought it could possibly be. It’s widespread,’” said Paul Brooks, professor of hydrology at the University of Utah and co-author of this study, which was published in the online science journal Ecosphere.

Swetnam explained that as water and soil move downhill, they collect on flatter slopes and valley bottoms creating favorable environments for trees to grow large and healthy.

The discovery adds a twist to ecologists’ current explanation that as elevation increases, so does biomass. The reasoning is that higher elevations usually mean more rainfall and cooler temperatures, the preferred climate for trees.

Swetnam pointed out that this is an incomplete picture. The variation in topography that mountains provide actually creates pockets for trees to thrive.

Mountains also create clouds that produce rain, a process not possible in flatland forests. Moreover, they capture and direct water and soil, making the view of forest ecosystems richer than previously thought.

Researchers studied a forest in Colorado but said this pattern is consistent across different kinds of forests around the world, including the mountain forests in Southern Arizona.

Ultimately, Swetnam said, what his study reveals is that “It’s not just a pure elevation thing. It becomes a topographic position thing.”

The roots of society

Society as a whole relies heavily on forests, Brooks said, so understanding how they work as a system is beneficial to us.

Trees take in carbon dioxide, sunlight, water and nutrients from the soil to build the various parts of the tree. In doing so, they remove carbon dioxide from the air.

“As trees get bigger, they’re storing more carbon,” Swetnam said. “But they’re also doing more metabolism because there’s more leaves on these big trees. So not only are they bigger, but they’re also pulling in more carbon.”

And knowing where trees can grow biggest and densest is important, said Swetnam.

“If you’re calculating continental-scale carbon budgets for an imaginary carbon tax, you could be off (in your predictions),” he said. “So how are we going to calculate large-scale carbon dynamics if we don’t have the right kind of maps?”

There’s another benefit to trees: They have the ability to affect the amount and quality of water that is available to humans.

If there are too many trees, they absorb so much snowmelt and rainwater that not much flows downstream. Too few trees would allow water and snow to evaporate quickly. In either case, that doesn’t leave much water for us downstream.

“You actually get the most amount of water when you have a moderately dense forest,” Brooks said.

Forest management

All of this ties back to how different topography impacts tree growth, and ultimately influences conversations about how to manage forest land, especially in the face of climate change.

“We’re going to experience more frequent droughts. It’s going to get hotter and drier,” Brooks said, adding that certain places, like the valley bottoms of mountainous terrain, can be less susceptible to drought.

Rain and snow “can fall and do no one good, or it can go to trees to sequester carbon or go downstream for people,” Brooks said, depending on how the land is managed.

“If we help our forests develop in a more natural state, no designer forests, by understanding forest structure and what controls it, we have the ability to minimize wasted water,” Brooks said.

“From the water perspective,” said Laura Briefer, water manager with the Salt River Project utility district, “we’ve always understood that healthy forests in mountainous areas are important for water retention and filtration and generally help systems work more efficiently and effectively.”