The jeep lurches over the rocks, nearly jolting the GPS out of Aaron Wright’s hand. He steers the vehicle to the top of a gully and peers at the map in his lap. He took a wrong turn somewhere.

He deftly turns the car around, and off we go bouncing through the desert. We’re in the Sonoran Desert just northwest of Gila Bend, looking for the trail that will lead us to a gallery of rock art along the old floodplain of the Gila River.

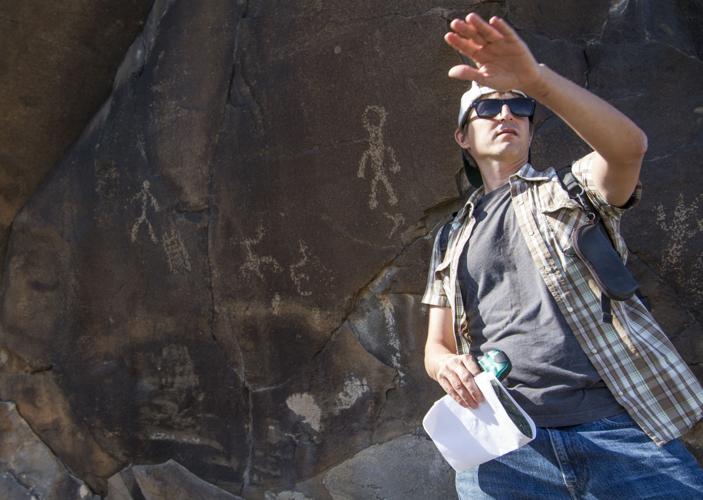

Wright is a preservation archaeologist with Archaeology Southwest, a nonprofit conservation organization based in Tucson. He’s been studying the Great Bend of the Gila River for two years as part of an effort to turn the area into a national monument.

U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva reintroduced legislation in Congress in June to designate 84,000 acres of land along the river as a national monument. He had initially introduced it in 2013, but the bill was unsuccessful.

“Nothing’s getting done in Washington in terms of this kind of legislation,” said Bill Doelle, the president and CEO of Archaeology Southwest. “But we will continue to work because we think this is incredibly important.”

After a three-hour drive from Tucson, the GPS coordinates finally tell Wright that we’re in the right spot. He pulls off the dirt road alongside a patch of “desert asphalt” — the old lava flows that dot the otherwise sandy landscape.

A myriad of peoples have lived here over the centuries, like Yuman-speaking Native Americans and their ancestors, called the Patayan, but now there’s hardly any signs of civilization out here. For a while, a lone power line marked the path, but on top of the mesa that is serving as our parking spot, it truly feels like we’re out in the middle of nowhere.

“There’s a long history, in American history, of perceiving this environment and landscape as abandoned, or vacant, or a no-man’s land,” Wright said when we first met at his downtown Tucson office. “But that’s incredibly far from the truth.”

We walk to the edge of the mesa and look down. Much of the once-fertile floodplain has been overrun by invasive tamarisk trees, but Wright points out an alfalfa field. We’re not so alone after all. This historical agricultural area is still being used to grow crops.

“People have been hanging out here for a really, really, long time, and still to this day,” he says.

Even though this area has been populated for thousands of years, it’s been fairly untouched by researchers, which is part of the impetus for establishing the Great Bend as a national monument.

“The area has never been fully surveyed and inventoried, so we know where sites are, but we also don’t know where sites are,” Wright said in his office. “No one has actually gone out there and mapped them.”

“It just hasn’t had that level of professional attention that it deserves,” Wright says as we make our way down the side of the mesa. We scramble over boulders and weave around creosote bushes and mesquite trees as we traverse the cliff side.

Then the petroglyphs come into view.

Wright said the first time he saw the rock art at Oatman Point, he was overwhelmed by the sheer number of petroglyphs painstakingly pecked, rubbed and scratched into the desert varnish on the cliff.

“I studied petroglyphs for my Ph.D. dissertation, so it wasn’t like something I’d never seen before, but this context is really different than anything I’d ever experienced before, studied before,” he says. “It’s some of the most significant rock art in North America … we think it’s world-class.”

He is careful to not touch the ancient art as he describes the imagery. The cliff face is completely covered in humanoid figures, hands, snakes, big horn sheep, suns and so many more images that are indistinguishable.

He can only hypothesize the meaning of the drawings, but he doesn’t mind.

The ambiguity is part of the petroglyphs’ allure, he says.

More than 100,000 are estimated to decorate the rocks along the lower Gila.

Some are cut through with faint scratches. It’s not graffiti, Wright explains, but a possible indigenous tradition to access the spiritual power within the petroglyphs. Scratching through the art was intended to release the energy.

Because of their color and proximity to village remnants in the floodplain, he estimates that the majority of the petroglyphs are between 500 and 1,000 years old. Some look like they could have been made yesterday.

The rock face is basalt, which is more stable than something like sandstone, he says. The cliff-side is also well-sheltered, which has helped preserve the art. And it’s hard to get to.

“The number one issue with rock art preservation is human impact,” Wright says. “We’re probably one of a couple hundred people who have been here in the last 20 years.”

There is scant protection for the petroglyphs. The area is federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, meaning that anyone can wander out here. It is designated an Area of Critical Environmental Concern, which Wright said is a low level of protection — “better than nothing, but it’s also not permanent.”

As the Phoenix metropolitan area continues to expand, that growth will encroach on these delicate areas. Some sites on the eastern edge of the Great Bend have already been vandalized. As the population increases, Wright said, the impact on unprotected areas will grow exponentially.

If the Great Bend of the Gila becomes a national monument, it still won’t be off-limits.

“The national monument effort isn’t about keeping people out of these places; it’s about managing impacts to the landscape,” Wright said. “This is a history that everybody should appreciate; we just don’t want people shooting petroglyphs.”

After traversing the side of the mesa and seeing the outdoor art exhibit of petroglyphs covering the cliff, we clamber back up to the top. The art disappears from sight.

“It’s been a transportation corridor for millennia,” Wright says as we come across wheel tracks on the mesa, presumably from a stagecoach route that passed through here over 150 years ago. The history of travel in the West is written on the landscape.

The riverbed of the Gila River stretches for more than 600 miles across parts of Arizona and New Mexico. The river was stoppered by a series of dams along it and its tributaries — the Salt and the Verde — but when it flowed freely, the water guided travelers across the desert.

In 1846, the path through the desert alongside the river became known as the Mormon Battalion Trail. Before that, it was called the Gila Trail. In 1851 it became the Cooks Wagon Road. Seven years later, it took on the moniker of Butterfield Overland Stage Route. Throughout the decades, it’s also been referred to as the Southern Immigrant Trail.

“It used to be a very reliable source of water,” Doelle said. “Any travelers, up until freeways and railroads were built, stuck very close to the river.”

Along with providing lifesaving water, the river also made farming along its banks possible. To the numerous people who depended on the Gila, the river provided food, water, and a safe path through an otherwise inhospitable desert.

Wright bends down to look at the wheel marks more closely.

“Once they’re pressed on to this desert pavement, they’re here forever,” he says of these traces of transportation, as long as they remain relatively undisturbed by humans. But, he points out, there’s nothing stopping a modern vehicle from driving over this piece of American history.

Walking along the mesa, Wright points across the riverbed to a small hill with a trail going straight up it. That’s called a summit path, he says.

Other lines and patterns on the ground are called geoglyphs, which are probably the least understood part of the Great Bend, he says.

Rock formations and faint trails connect seemingly unrelated areas along the river.

Out of context, they appear to be just that — random markings on the ground. But viewed within the context of nearby petroglyphs, villages, and other geoglyphs, they have meaning.

Some appear to be drawings meant to be viewed aerially, while others look to be ancient paths connecting culturally important sites.

Many of these interrelated glyphs are designated as separate entities. But to understand them, they have to be studied as a whole, which is part of the reason why the national monument effort seeks to preserve the cultural landscape of the area, not just certain sites of interest.

“We have a tendency to focus on archaeological sites as these discrete units, and so we impose boundaries on places, but a careful attention to the interrelationships of archaeological properties reveal a pattern and a structure that basically makes some of the sites’ significance their relationship to other sites and to the surrounding environment,” Wright said before we ventured to the site. “The landscape is greater than the sum of its parts.”

We hike up an arroyo that carries rainwater down to the main channel of the Gila during monsoons. When we reach the top, Wright points out a cross scratched onto a rock, along with an illegible inscription. Other names and dates dot the boulders.

Western settlers passed through here. Money seekers trekked by on their way to capitalize on the California Gold Rush. Spanish missionaries ventured along the Gila to find a land route to the Pacific Coast, instead of having to travel by ship.

“The Great Bend of the Gila as a preserve would be archaeological, but the story it tells is one of multiculturalism,” Wright said.

The Gila River can teach us all something, he said in his office before we explored its dried-up banks. Because the story the land tells is one of people, and humanity.

“We can definitely learn about past peoples … and try to understand the communities that lived here before and how they managed to deal with one another, their long history of human struggle and triumph in one of the most inhospitable environments in North America,” Wright said.

We continue along the Oatman Road, then to Rocky Point Road, until it meets up with Painted Rock Dam Road. It’s a bit of a jolt when the tires touch pavement again, and the short drive to Painted Rock is oddly smooth.

Wright pulls off into a parking lot — an actual parking lot, not just an arbitrary spot in the desert — and gets out. Painted Rock used to be a state park, but it was turned over to the Bureau of Land Management in 1989.

The site features covered eating areas, informational signs, and a trail winding around the main attraction.

Hundreds of rocks are piled in a 50-foot-tall mound. On the south side, each rock is covered with petroglyphs.

After our scramble to see the petroglyphs on the side of the mesa, the small hill of rock art seems to clash with the neat picnic area and RV camping.

If the effort to turn the Great Bend of the Gila into a national monument succeeds, Painted Rock would be included.

“There was actually an attempt to make this place a national monument in 1938, and again in 1983, and again in 2000,” Wright says as we walk around the rocks.

People used to steal the rocks, he says, or climb on top of them. There used to be a fence around the site, but the BLM took it out in the ’90s and put up the signs.

“It’s been effective how they’re managing it,” he says. “There hasn’t been a case of vandalism since 2000.”

A couple tourists wander around, discussing what the various petroglyphs might mean, snapping pictures, peering closely at the rocks.

The rest of the land would not be developed like Painted Rock if the Great Bend did become a national monument, Wright says. There won’t be a paved road or stairs to take visitors to the petroglyphs at Oatman Point.

But tourists can still learn about the people who have lived here throughout the years at Painted Rock, and those with an adventurous spirit will be able to make their own trek out to the remote petroglyph sites. And Wright and other archaeologists would have the opportunity to fully research and document the area without fear of its destruction.