For the first time in more than a decade, visitors to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument can wander at will among the 330,000 acres that make up one of the most biologically diverse protected areas in the region.

Portions of the park had been closed after a ranger was killed in 2002 by a man fleeing Mexican police, leading to the park being called one of the most dangerous places for rangers to work.

As the number of Border Patrol agents and infrastructure increased, park officials started to review traffic and smuggling through Organ Pipe to see if any portions could be reopened. By 2012, more than half of the park was open to the public. This year, with a new superintendent, officials decided to go all the way.

“We went ahead and made the big jump because it was time,” said Sue Walter, spokeswoman for Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, which gets its name from the pipe-organ-shaped cactus native to the area.

“It’s public land, we had everybody in place, the Border Patrol was on board with it,” she said, “so it’s now just letting the visitors know what’s out there, what they can encounter, and letting them make their own decisions of where they want to go and how safe they feel.”

The park has about 20 rangers, up from four when Kris Eggle, 28, was shot. The Border Patrol’s Ajo station has gone from about 25 to 500 agents. The Office of Field Operation at the nearby port of entry in Lukeville has also increased from 12 to 32 officers.

It is also equipped with sensors, surveillance towers, a Border Patrol forward-operating base, a 30-mile vehicle barrier and a 5-mile pedestrian fence.

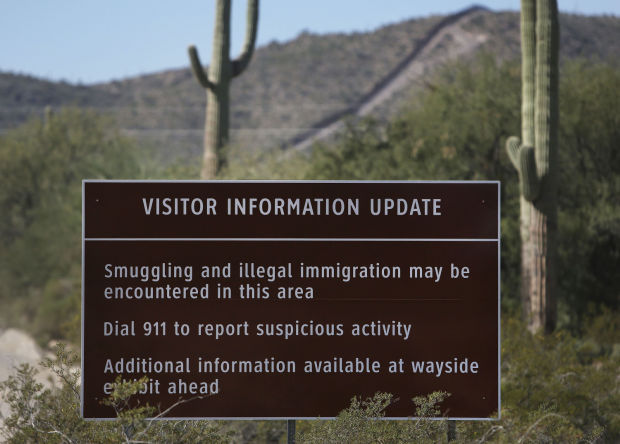

Signs throughout the park warn people that they may encounter smugglers and border crossers and ask visitors to report suspicious activity.

Staff members haven’t seen a huge spike in visitors since the park reopened in mid-September, but they are getting calls every day. They’ve even had one backcountry camper, which hasn’t been allowed for years.

On a recent visit, Kay Hackleman was just happy to hear it was reopened. She and her husband had done the 50-mile loop years ago and wanted to do it again.

“I may do it tomorrow,” she said as she left the Kris Eggle Visitor Center.

• • •

Life at Organ Pipe was not always all about drug smugglers or border crossers.

Before traffic was pushed from places like El Paso, San Diego and Arizona urban areas, such as Nogales and Douglas, Organ Pipe was about learning and experiencing one of the largest protected areas, home to endangered species such as the Sonoran pronghorn and the lesser long-nosed bat, said Sue Rutman, who worked there from 1994 until she retired as the plant ecologist last year.

It’s still a beautiful place, she said, but so much of what goes on now is dictated by border issues and the needs of the Border Patrol.

Hard statistics of traffic through Organ Pipe are not released. The park stopped releasing what its rangers were seizing and apprehending. And the Border Patrol provides numbers only by sector or corridor, not by specific area. Organ Pipe falls in the western corridor.

According to Star archives and congressional reports, in 1997 park rangers seized fewer than 1,000 pounds of marijuana, but that jumped to 14,000 pounds by 2001.

Arrests of border crossers on federal land in Arizona went from fewer than 5,000 in 2000 to more than 200,0000 in 2002. At its peak, the Border Patrol estimated that as many as 300,000 people went through Organ Pipe in one year.

The border was divided by a barbed-wire fence that could easily be cut, so cars and groups crossed through regularly. Groups of 60 to 100 people were common. Agents and park staff describe foot trails more than 10 feet wide.

“You’d drive to work every morning and there would be people on the side of the road giving up,” because they couldn’t walk anymore, Rutman said.

There would be abandoned vehicles in the middle of the wilderness.

Through the years she saw difficult things, including bodies — more than 100 remains have been found at Organ Pipe since 2001 — and young girls being brought by older men Rutman suspects were to be prostituted.

An image that remains with her is that of a mother carrying an infant. She saw them one drizzly winter morning.

“The park rangers had apprehended this group of about 10, 15 people and one of them was this woman holding an infant in her arms, no rain gear or anything, just regular clothing, no shoes. I thought, ‘What did you come from to make you walk through the desert, to bring your baby in the rain, to make you want this?’,” she said. “At the same time you feel this anger the cartels are taking over my park.”

When Eggle was killed on Aug. 9, 2002, the park was understaffed. It had fewer than 30 Border Patrol agents and four rangers. It had been approved for eight positions but only filled four to cut costs.

At first, Rutman said, they were mostly migrants led by independent smugglers, but later cartels took over. They owned roads and trails at Organ Pipe.

Staff members learned to recognize differences between smugglers and border crossers and to walk away when they found themselves in the middle of a group.

In 2006, the park stopped granting most new research permits. Even staff members had to be escorted to work in certain areas, the “red zones.” In others, they had to travel at least with one other person and report in hourly.

• • •

While the massive number of agents and other law enforcement patrolling the park has helped reduce traffic, that hasn’t happened without impacting the same resources the park is there to protect.

Thousands of roads have been illegally created over the years, damaging soil and vegetation. A five-mile, 15-foot-tall pedestrian fence, erected in 2008 west of the port of entry, has led to flooding.

The Border Patrol is working with the park on several restoration projects, including the closure of roads to restore the land to its natural state, said Reggie Johnson, supervisor at the Ajo station.

But restoration is slow in the desert, former park employee Rutman said. She was leading the $3 million restoration project before she left. “There are roads that haven’t been used for 100 years and are still visible on satellite imagery.”

Also, the feeling of solitude is hard to achieve with surveillance trucks, ATVs and towers dotting the desert landscape.

Roger McManus, with Friends of the Sonoran Desert, remembers his first trip to the area several decades ago.

“You truly felt you were in the wilderness, that you were on your own. It was spectacular,” he said. Now it’s hard to escape human presence, traffic and motorized vehicles.

They still need to figure out how to best protect the border, he said, while preserving the land.

• • •

Despite their dueling missions, the Border Patrol and park have realized that their missions are not exclusive of each other, park spokeswoman Walter said.

Peter Bidegain, spokesman for the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, said the agency is working hard to educate agents about the land. The Ajo station conducts joint trainings and works hand-in-hand with park rangers, and has a community liaison that works closely with the park’s staff.

During a recent ride-along, Border Patrol supervisor Johnson pointed to a solar-powered light across the border fence that recently replaced a diesel light. It’s a sign of the Border Patrol’s efforts to be more environmentally friendly, he said.

Controversy about agents’ presence remains, but there is no disputing that working together has helped achieve better control of Organ Pipe, said Brent Range, park superintendent.

For example, the 3-foot-high multimillion-dollar vehicle barrier that went up in 2006 pretty much stopped vehicle traffic from Mexico.

The number of people caught in the western corridor, which includes Organ Pipe, has decreased by more than half from fiscal year 2011 to 2014, from about 53,000 to 23,000 through Aug. 31, 2014 — one month before the end of the fiscal year.

People need to see how beautiful Organ Pipe is, former employee Rutman said. But they also need to know that, while smuggling in the area is reduced, it’s still a reality.

“There are certain areas that are known corridors and probably will always be,” she said.

Only a few years ago, Rutman said a smuggler jumped into the back of her pickup truck.

“That was terrifying,” she said. The man wanted some water that was in the back of the truck. She kept driving and he jumped out after about a quarter mile.

Ellen and Fred Merrifield, from Washington state, said they weren’t deterred during a recent trip.

It was their first visit to Organ Pipe after friends told them it was at the top of their list of things to do.

“Just driving in is so special. All the saguaros and cacti, it feels like a forest,” said Ellen.

In regards to law enforcement and potential traffic, “if you do what they suggest and be careful where you stop,” Fred said, you should be fine.

“Why not enjoy something this beautiful?” Ellen said as they figured out where to head first.