Following a five-hour drive east from Tucson, the New Mexico morning desert sky cast itself in Robin egg blue. The heavens were salted with feathery trails of see-through lacy clouds drifting to the south in a nomadic weave with little encouragement from the airstream. Flecks of wildflowers gently opened to the sun’s warmth, creating a spectrum of hues as the April morning temperature acceded to 65 degrees by 10 o’clock.

I was standing at Trinity, ground zero, where the first atomic bomb exploded on July 16, 1945, at 5:30 a.m., causing seismographs in Tucson to go off detecting the explosion 280 miles away. The test bomb, code name Gadget, would have been suspended from a steel tower approximately 96-feet directly above my head. Upon detonation, it produced enough energy to compress the ground below me ten-feet into the earth’s crust. The one-hundred-foot steel tower vaporized.

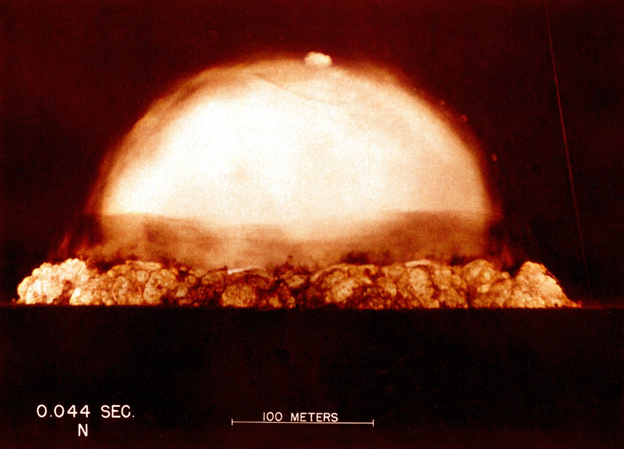

On that morning in 1945, a spectacular white flash of heat and light blanched the barren landscape. Initially, tongues of fire shot out at ground level and splashed across the desert floor. Yellow, green, and scarlet flashes came from the hemispherical plume. It rose rapidly like an enormous sweltering blister and popped. Then, immediately gushed up and up, boring a hole into the heavens, belligerently tearing for air and room to grow. As the cloud stem reared, it appeared twisted like a left-handed screw. The mass soared into the atmosphere more than 40,000-feet in the early morning sky. The sun rose twice that day and a blind girl, 120-miles away, said she saw the flash.

The Atomic age had shown its teeth to the world for the first time.

Seconds later, the thundering sound echoed against the Sierra Oscura Mountains, the rocks, and the desert floor, for what seemed an eternity to observers. The sound was nearly defining as it bounced over and over in the Jornada del Muerto. This area in the desert is known ominously from Spanish times as the Dead Man’s Trial—The Journey of Death.

Less than a month after the Trinity test, at 2:45 a.m. on August 6, 1945, pilot Col. Paul Tibbets took off in the Enola Gay B-29, from Tinian, part of the Mariana Islands in the Pacific. “Dimples 82” was loaded with the four-ton bomb named “Little Boy,” bound for Hiroshima.

In discussions with one of the senior guides at Trinity, he asked me who I thought was the single individual most responsible for the U.S. producing the atomic bomb. Prominent names were recalled. Then he stated: Hitler. He added that before the war, Hitler forced the most brilliant scientific minds from the Jewish community in Germany out of the country. The massive depth of mental aptitude and technical skills of these engineers came to work in the U.S. and helped develop the Manhattan Project.

The site is open twice a year to visitors, the first Saturday in April and the first Saturday in October. The White Sands Missile Range is under the command of the U.S. military.

As I walked out of the squared-off fenced and gated sector containing the Trinity National Monument, I heard a slight ticking sound following from behind. It came from a fellow carrying a Geiger Counter. A grave reminder of what man produced at this very site, which to my vexation, was still ticking.