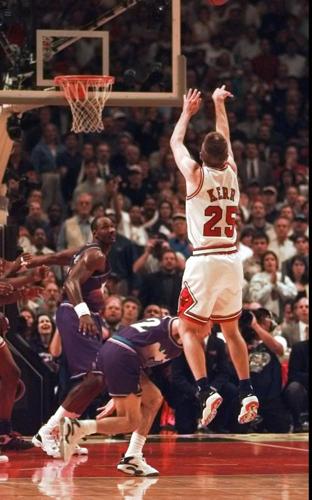

Steve Kerr played 15 seasons in the NBA, hitting 726 three-pointers. None was bigger than the shot he hit in Game 6 of the 1997 NBA Finals. Here is Greg Hansen’s June 15, 1997 column:

On Friday night in Game 6 of the NBA Finals, game tied, six seconds to play, Steve Kerr took a pass from Michael Jordan and had an open 18-footer.

It was the chance of a lifetime.

Thousands of basketball players come and go and never find themselves in precisely the right moment at precisely the right time.

All that was left was to stand up to the pressure.

Steve Kerr had played more than 12,000 minutes in the NBA — roughly 720,000 seconds. In an instant, without warning, the 720,001st second of his NBA career would be the ultimate confluence of opportunity and reward.

The Shot would be his to take.

After a lifetime spent introducing himself to pressure, Steve Kerr didn’t hesitate.

Real pressure

This is pressure: In August 1983, Kerr was at the airport in Beirut, Lebanon, preparing to fly to Tucson to register for his freshman year in college.

He was traveling alone, embarking on the grandest experience of his life, sight unseen. Kerr had never been to Tucson, never had time to take a campus visit after Lute Olson offered him a scholarship in late July of ’83.

Hell, Olson didn’t publicly announce Kerr’s addition to the UA squad until Aug. 29 of that year, 12 days after school had been in session.

As Kerr was waiting to board his plane that day, a 122 mm Druse rocket exploded, rocking the Beirut airport. He was 18 years old, and he thought it could be his last few moments on Earth. … Several days later, pulling strings, Malcolm Kerr, president of the American University, arranged for his son to fly out of a U.S. Marine base nicknamed “Sandbag City” where 1,200 Marines were encamped.

He would fly on a diplomatic jet through Cairo, Egypt. But just as Kerr arrived at the air base, the flight was scuttled.

Finally, three days after trying to leave Lebanon, Kerr agreed to a harrowing plan. It was decided that he would be driven, before dawn, by a friend of the family past Druse outposts, through Syria to Amman, Jordan. There he would catch a flight to Cairo and then to the United States.

The drive took 10 hours, requiring several stops at military checkpoints.

Kerr reached Tucson two days later.

His father would be dead, killed by assassins, 4½ months later.

Maybe that’s why taking a jump shot under duress, even an 18-footer with the NBA title at stake, doesn’t seem to rattle Steve Kerr.

The game of his life

In the 10 years since he returned to basketball, his right knee fully rebuilt, Kerr has bounced around some. He was traded by Phoenix to Cleveland, and by Cleveland to Orlando. He sat on the bench in long spells, stacked up behind some not-so-immortals such as Jimmie Oliver, Litterial Green and Chris Corchiani.

In his first seven years in the NBA his highest average was 3.2.

He was traded by Phoenix for Mark Buford.

Cleveland traded him for Amal McCaskill.

When he finally signed a free agent contract with the Bulls, in 1994, Jordan left the team to play baseball.

Kerr seemed, almost chronically, to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Who could’ve known what was in store?

Who could’ve guessed that with six seconds left in the Game of His Life, world championship on the line, Michael Jordan would see him standing there. Open.

Nothing but net.