The best football player in Arizona history woke up early on Thanksgiving morning 1935 and walked from his parents’ house on Ninth Street, five minutes at most, to Bear Down Gym.

He ate an early Thanksgiving dinner with his 32 teammates and prepared to play the last football game of his life.

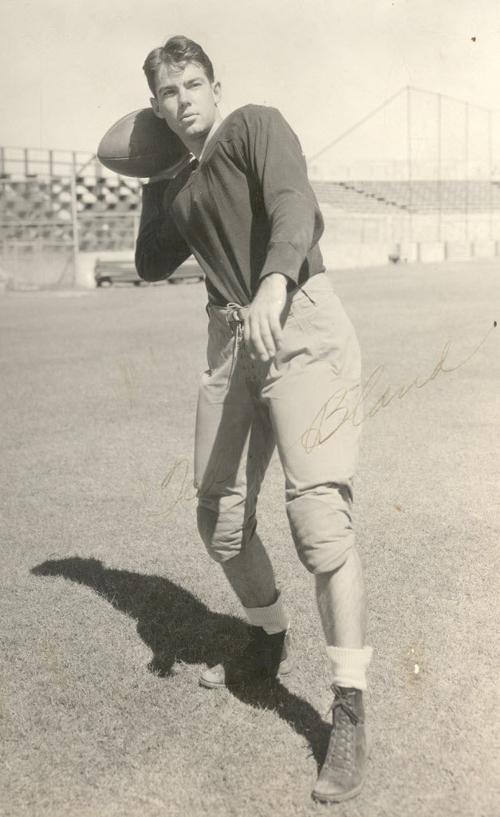

By the time Ted Bland pulled jersey No. 15 over his head, more than 8,000 people squeezed into 6-year-old Varsity Stadium to watch the “Blue Brigade” play the Drake Bulldogs.

“I don’t remember the details of the game,” Ted’s younger brother, retired Tucson oral surgeon George Bland says now. “But I was sitting in the old Knothole Club and I do know that Ted scored a couple of touchdowns.”

The Star’s headline the following day said “Invaders Powerless as Bland Leads Mates to Victory.”

Arizona won 53-0. Two weeks later, Bland was named a first-team “Little All-American,” which was that era’s equivalent of today’s Division II All-America team.

At Saturday’s UA homecoming, 80 years later, you can see Ted Bland’s name in the Ring of Honor, just above the 25-yard line, no more than a long field goal from the old home of Allen and Iris Bland.

In 1935, Ted Bland was the biggest name in Arizona sports. He was twice an all-state second baseman, 1931 and 1932, at Tucson High School. He was captain of the Badgers’ basketball team, and in 1931 he was the state’s top quarterback. He scored seven touchdowns in a game against Bisbee, which remained a state record more than 50 years.

“He was just a tough sonofagun,” his former THS and UA teammate Leon Gray told me in a 2004 interview. “He couldn’t have been more than 145 pounds but he played like a guy who could knock your block off.”

Allen Bland, a farmer’s son from south Texas, moved to Tucson in 1908 and raised a family of three boys — Ted, George and Allen — while working for the Southern Pacific railroad.

“Ted’s real name was Vernon,” George says. “But no one called him that unless he got in trouble.”

Ted got in trouble in a 1935 loss to Loyola. He either broke or dislocated a rib, but he didn’t tell coach Tex Oliver. Struggling and in pain, Bland completed just one of eight passes in the 13-6 setback. A week later, against New Mexico State, Oliver demoted Bland to the second team.

Oliver was so upset that he did what today’s college football coaches do: According to the Star’s archives, he closed practice to fans and local reporters and tried to devise a way to beat New Mexico State without his star quarterback.

But during the week, unknown to Oliver and the UA trainer, Bland went to a local physician and received an injection to help numb the pain. After his team struggled in the first quarter, Oliver inserted Bland. Arizona fought back to win 9-6.

The Star reported that “Brigadier Bland” rallied his team from behind.

If that doesn’t get your name in the school’s Ring of Honor, after a 7-2 season, a career record of 19-7-1 and three successive years as the All-Border Conference quarterback, what does?

“I didn’t know Ted personally until he had left college; he was a good friend of my uncle,” says Lt. Col. (ret.) Francis “Babe” Hawke, a World War II Air Force bomber pilot who graduated from Tucson High and the UA. “But from reputation, he was a great football player, a big name.”

Oliver’s “Blue Brigade” was so impressive in 1935 that a Phoenix group arranged to stage a bowl game, Arizona vs. TCU, on Dec. 14. But someone in Bland’s Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity was diagnosed with scarlet fever. As was the medical practice of the time, all of those in the SAE house were quarantined for a week.

There would be no bowl game. Ted Bland’s football career was over.

The New York Giants sent a scout to Tucson and signed Bland to a baseball contract. They sent him to Palestine, Texas, to play second base for the Class C Palestine Pals, but after hitting .206 in 42 games, Bland got on with life.

He worked for the FBI, the Border Patrol and the railroad. By 1942, he was at Fort Benning, Georgia, part of the Seventh Army, a different type of brigade, an infantry brigade, that would fight the Germans mile by mile in Italy and France.

The best football player of Arizona’s first 35 years of football was reported missing in action in late September 1944. Two weeks later, a telegram arrived at the Bland home on Ninth Street.

Their son had been killed by a bullet of a German sniper. He was buried at the Epinal American Cemetery just above the Moselle River in Dinozé, France.

Seventy-one years ago today, a headline in the Tucson Citizen said:

UA’s Mighty Mite,

Ted Bland, Killed

Now his name is on display at Arizona Stadium’s Ring of Honor, bottom row, seventh from left.

Every time I stand for the national anthem at Arizona Stadium, I think of Ted Bland. It’s about so much more than football.