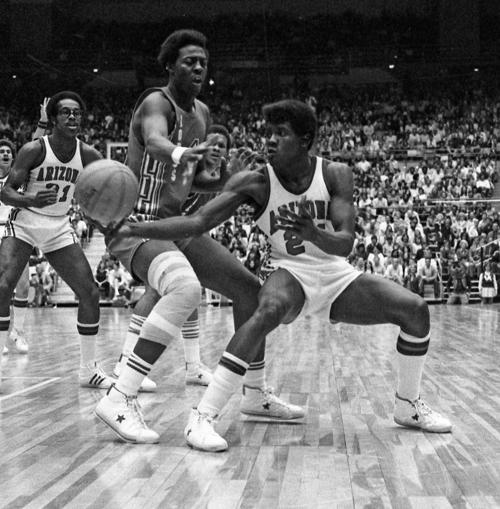

Herman Harris played his last basketball game at McKale Center on Feb. 26, 1977. He scored a game-high 20 points against Wyoming, became a first-team All-Conference guard, was drafted by the Philadelphia 76ers and went on to live happily ever after.

That’s the script for today’s college basketball star, isn’t it?

“Right. … Rich and happy,” Harris said Monday, a few days before his 64th birthday. “Sometimes they don’t tell you there’s more than basketball.”

Last Friday at the UA Student Union Grand Ballroom, Herman E. Harris, son of a cook and house-cleaner from Chester, Pennsylvania, a Parade All-American in 1973 whose father was murdered when he was 3 years old, wore a new uniform.

He put on a cap and gown and walked across the stage to receive his college degree.

“I think everybody had tears in their eyes,” said Jerry Holmes, the man who recruited Harris to Arizona’s basketball program all those years ago. “I don’t know if I’ve ever felt better in my life than when I watched Herman get that diploma.”

Over the last 40 years, life-after-basketball became manifest for one of the leading ballplayers in UA history. Harris spent 14 years in the Army, worked 20 years at the Pima County Superior Courthouse, got married, raised a family and, six years ago, chose a path not frequently traveled.

“My wife (Robin) and I have been raising my granddaughter who is now a senior in high school,” he said. “I chose to go to the NBA, to play basketball, after my days at the UA, but I didn’t finish school. In 2011, I decided I wanted to set a better example, so I went back to school. Little by little, I got it done.”

None of those who shared UA classes with the modest Harris had an idea this “older gentleman” in the class once scored 35 points in back-to-back 1977 Arizona victories against Utah and BYU. None could have known that as a Pennsylvania schoolboy, Harris once had the triple-double of a lifetime: 64 points, 30 rebounds and 10 blocked shots in a 1971 game against Oxford High School.

And, certainly, none had any idea that Harris, who grew up in Chester, a Philadelphia ghetto where, he says “the crime rate was crazy,” was lightly recruited even though he was one of the five or 10 leading prospects in the high school Class of 1973.

“Nobody came to Chester, especially white guys, it was too dangerous,” he says now.

In the summer of ’72, Holmes, the recruiting architect of the UA’s first class of players for the new McKale Center — a list that included Detroit super-prospects and future NBA players Coniel Norman and Eric Money — was in Scranton, Pennsylvania, scouting summer tournaments.

Holmes had never heard of Herman Harris.

“It was divine intervention,” Holmes said Monday, chuckling at the memory. “I was reading the local newspaper and it included a small note on a tournament being held that day in what turned out to be the basement of a small church. When I got to the church, I was basically the only person in the gymnasium except for the Chester High School coach, Juan Baughn.”

Harris, a 6-foot 5-inch junior with a muscular frame, walked onto the court wearing a cast on his left foot, which he had broken a few weeks earlier.

Holmes introduced himself to Baughn and the conversation turned to the young man with a broken foot.

“Watch him shoot,” said Baughn. “Watch his touch. He’s got great range. He’s an all-star.”

Holmes asked if anyone was recruiting Harris.

“Not really,” he said, although Florida State and Utah would soon discover Harris, too.

Baughn got Harris’ attention. “Dunk a few,” he said.

On one foot, Harris elevated and slammed a few basketballs through the hoop.

“My God Almighty,” Holmes said Monday. “Three months later we had Herman and his teammate, Len Gordy, on a recruiting visit to Tucson. We got both of them.”

With future NBA players Norman, Money, Bob Elliott and Al Fleming as Arizona’s go-to scorers on a team that would be ranked as high as No. 12 in the AP poll, Harris, a freshman, had to get in line. He averaged 7.6 points and 18 minutes per game.

In today’s college basketball culture, a prospect of Harris’ status might’ve transferred to a place where he could get more shots. But the son of Anna Harris, who was a cook at the Brandywine Racetrack in Wilmington, Delaware, wasn’t one to run from a challenge.

“My mother raised four kids by herself, working two jobs,” he said. “She was a no-nonsense person who took us with her to church every Sunday. When I told her I was going to Arizona, she knew it would change my life. She said, ‘There ain’t no turning back; they were nice enough to give you a scholarship, so you honor that commitment.”

Forty-five years later, Anna’s son turned that scholarship into a diploma.

Harris isn’t yet sure what he’ll do to implement his degree. He might start as a volunteer coach at the high school level, or in a Tucson youth league.

But he is sure that when he walked across the stage in a cap and gown last Friday, his mother was smiling down from heaven.

“This is not about basketball, it’s about life,” said Holmes, who coached at Arizona until 1982. “It’s about a young man who moved to Tucson and grew into a man that his family and this community can be proud of.”