The day after Susan Chandler died of brain cancer last August, the Arizona Interscholastic Association informed her son, Sabino High School baseball coach Mark Chandler, that the Sabercats’ 2018 state championship was being revoked. A week later, Chandler was diagnosed with Stage 3 throat cancer, infecting his tonsils, neck and lymph nodes.

“As you can imagine, I couldn’t fight back,” says Chandler, who served in Operation Desert Storm as a Marine after he graduated from the UA. “It was the worst time of my life.”

The magnitude of any coach having a state championship taken away by the Arizona Interscholastic Association, or by anyone, is overwhelming.

It was the only time that a state championship in any of the AIA’s boys sports — baseball, basketball, football, track, wrestling, tennis, swimming, volleyball and golf — had been vacated. That covers approximately 2,400 state champions over 107 years.

Such a punishment suggests that Chandler’s baseball team must’ve broken almost every rule in the AIA handbook.

Now, a year later, out of coaching and still reeling from the events of last summer, Chandler has other things on his mind besides the 2018 baseball season.

“My life is a roll of the dice every three months. Each one of those chemo sessions has been terrifying,” he says. “But I know the rules and I know I didn’t break any.”

After reading more than 110 pages of documents, emails, letters, statements and texts related to the AIA’s case against the Sabercats, I didn’t find anything to justify such a penalty.

I’m neither an attorney nor someone who had regular contact with the 2018 Sabino team or its coaching staff. But in the age of open enrollment, where high school ballplayers jump from one school to another with unprecedented frequency — playing offseason club ball for unfamiliar coaches from all over the city — it seems astonishing that Sabino was considered so outside the rules that its championship was revoked.

The case essentially revolved around two ballplayers from a nearby high school accused of having “prior contact” with Chandler before transferring to Sabino.

But the dates of those alleged charges of prior contact — hitting fly balls to outfielders in a summer league program where Chandler is an assistant coach — don’t match the prior-to-transfer charges.

Not only that, the two ballplayers in question both submitted hand-written statements saying they didn’t know — or speak to — Chandler until after they became Sabino students.

“The AIA and (the Tucson Unified School District) never had any evidence,” says Tim Gillooly, who was Chandler’s pitching coach at Sabino and Sahuaro and has remained on new coach Shane Folsom’s Sabercats staff. “They made a lot of assumptions but none of it ever lined up. They never even had a date of the alleged prior contact practice in June.

“I still have the pitching logs of those boys in question and neither pitched until after they officially transferred to Sabino, in July and September. There is nothing in those (110 pages of) documents that shows a violation happened.”

The AIA forced Sabino to vacate its 2018 title after ruling there was prior contact between two players and a coach.

Gillooly has researched the case for so long that he almost knows those 110 pages by memory. He says he often awakens in the wee hours of the morning, unable to sleep because of the injustice done to Chandler and the seven Sabino seniors who had their championship revoked.

The situation was triggered by the parent of a Sabino ballplayer whose son, a senior, did not play regularly — even though he was in the top 10 on the team in total at-bats. That parent waited until the day after the Sabercats won the Class 3A championship at Hi Corbett Field to send a 1,200-word email to David Hines, executive director of the AIA. The parent accused Chandler and his staff of “dishonest and immoral conduct,” among many other things. The parent ended his accusatory email with the words “God Bless.”

God did not bless what followed. For the next three months, investigators from TUSD and the AIA interviewed 23 Sabino players, parents and coaches, and some former Sabercats.

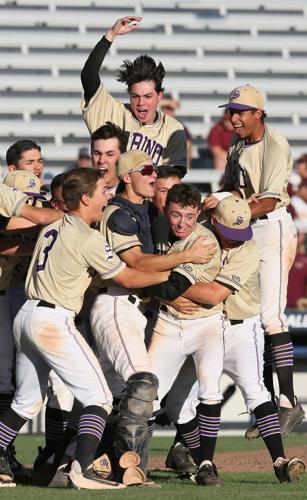

On Aug. 28, the day after Susan Chandler died in Casa Grande, the AIA revoked the championship. Mark Chandler then resigned as Sabino’s coach.

“I’m moving forward,” says Chandler, a longtime faculty member at Sahuaro High School who recently was told his cancer is in remission. “I can’t see myself coaching again, but who knows? I don’t know if I want to deal with the stress and craziness again.

“It seems like there’s always one parent out to get you, and this one got not just me, but seven seniors, including his own son.”

There is obviously no precedent of reviewing a case such as this in Arizona prep sports, or of restoring the championship and Chandler’s reputation.

Herman House, TUSD’s director of interscholastic athletics and president of the AIA, recused himself from the Sabino ruling. It didn’t mean he wasn’t affected.

“This whole Sabino thing really hurt me,” he said last week. “And I’m not just thinking about me, but those kids and their parents, the whole ordeal. It just took my heart.

“We’re talking about students. We’re talking about kids achieving and kids gaining success — and it had to be taken away from them. It’s one of the toughest things I’ve had to do in this seat.”

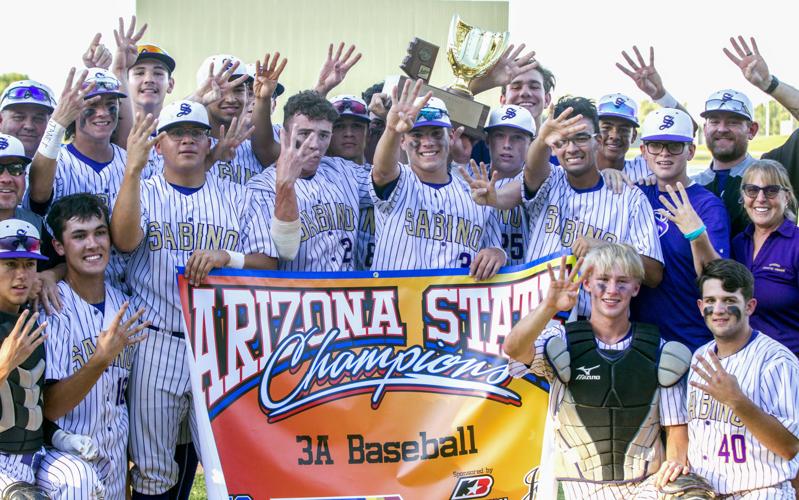

A week ago, Sabino won the 3A state title again. In the celebratory photograph holding the AIA championship banner, the Sabercats’ players held four fingers aloft. Chandler wore jersey No. 4 at Sabino. It was the players’ way of honoring their former coach.

Chandler is not sure if he’ll hire an attorney to sue the AIA in an attempt to clear his name and reopen the investigation. The expense would be significant, and it would open old wounds.

“It all just makes us look bad and we didn’t do anything bad,” he says. “To me, it’s a farce that was allowed to get out of control. This was mean and vindictive. It hurt a lot of kids needlessly.”