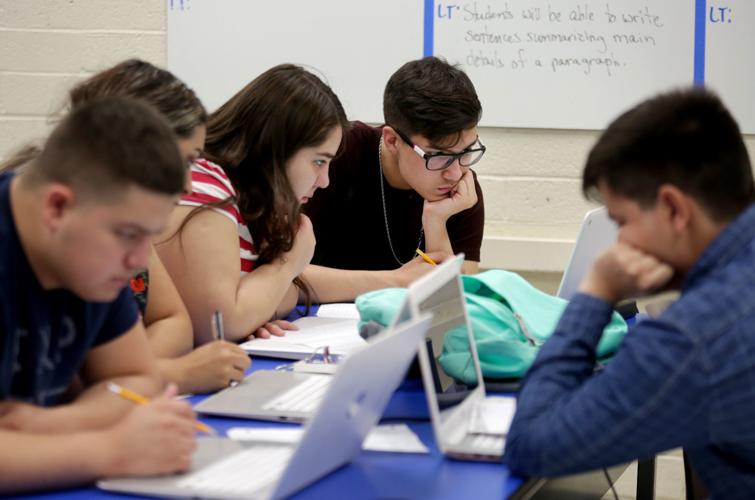

Students shuffle into John Rodriguez’s beginning English Language Development class at Sunnyside High School, greeting one another in Spanish as he tells them in English to open their laptops to an English reading assignment.

It’s the start of their 5ƒ-hour school day, four hours of which will be spent as a group in a single classroom, focusing solely on learning English, as required by state law.

But most of the classroom conversations are in Spanish.

The students hesitantly answer Rodriguez’s questions in English as he coaxes them out of their shells. But they quickly slide back to their native tongues when talking amongst themselves — which, despite Rodriguez’s stern command of the class, happens a lot.

That ironic conundrum of Arizona’s Structured English Immersion law — which was instituted as a result of the “English Only” Proposition 203 in 2000, and requires Spanish-speaking students to spend four hours a day segregated from their English-speaking peers — isn’t lost on the students or teacher.

Caleb Franco, an 18-year-old senior who moved to Tucson from Agua Prieta three years ago, thinks he would pick up English faster if he were forced to use it all day in regular classes. Instead, the temptation to speak Spanish with his friends in English Language Development class is too great, he said.

“We (are here to) learn English, but we talk Spanish in here,” he said.

And because he’s stuck in four hours of English every day, Franco, one of a handful of seniors in the 18-student classroom, won’t technically graduate on time.

Despite taking online classes on top of his regular course load, Franco still needs a health credit and will have to attend summer school.

The other students in the class nod with understanding.

Most have taken online or summer classes to keep up. None of them want to be here four hours a day, five days a week. They want to take electives like art, photography or automotive technology, or classes they need to graduate but can’t squeeze into their schedules, like geometry, health and history.

Rodriguez said the four-hour model is a “disservice” to the kids.

“I just think they’re being cheated out of other experiences and opportunities. One, they don’t get the classes they need. Two, they lose out on the practice they need because they would be forced to acquire the language at a faster rate in classes with English speakers,” he said.

But for more than a decade, those criticisms have fallen on deaf ears at the state Capitol.

Despite years of complaints from educators that the four-hour block, which is among the strictest English-language-learner laws in the nation, is detrimental to many English learners because it segregates them and doesn’t allow enough time in the school day to take other required classes, Republican legislative leaders have rebuffed previous attempts to change the law.

But things may be changing this year.

Two bills pending at the state Capitol would drastically alter the state’s Structured English Immersion program.

One measure, HB 2435, would cut that four-hour block to two hours for kindergarten through sixth-graders, and just 100 minutes for seventh- through 12th-graders, and allow school districts to front load that time, meaning ELL students could spend roughly their first two months of the school year in an ELL program, then integrate into mainstream classes.

Another measure, HB 2281, would allow ELL students to enter a dual-language program instead, which research shows is vastly superior for young English learners and helps students develop and retain skills in both languages, creating biliterate graduates.

Both bills are sponsored by Republicans. Similar measures sponsored by Democrats in the past went nowhere. Both bills have passed the House on unanimous or nearly unanimous votes, and both cleared the Senate Education Committee without any detractors.

But both bills have languished in the Senate Rules Committee, which they must clear before heading to a final vote by the Senate.

Republican Rep. Paul Boyer of Phoenix, chairman of the House Education Committee and sponsor of HB 2281, said in his eight years at the Capitol, “I’ve never seen such consensus on an issue as I see on this one.”

“People are starting to figure out that the current system isn’t working, that these kids are spending years in this immersion program, which is supposed to only be a year, but it never happens that way. And they don’t get content, so they’re missing out on math, science, history, everything else, and they’re so far behind they either don’t graduate or are just kind of pushed along,” he said.

“I guess I should have said, ‘Legislators are finally starting to figure that out.’ I think people in the field have obviously had it figured out for years,” he added.

But the bills’ fates are still uncertain. The Senate Rules Committee has met several times since the bills were assigned there, but Senate President Steve Yarbrough, chairman of the Rules Committee, has not yet put them on the agenda for a hearing.

Boyer said he has tried repeatedly to reach Yarbrough to urge him to hear the measures but has not heard back.

Yarbrough could not be reached for comment.

Lawmakers are aiming to close out the legislative session in the next two weeks.

LOW TEST SCORES, GRADUATION RATES

Arizona’s Structured English Immersion model came as a result of the “English Only” Prop. 203, but the proposition doesn’t actually call for a four-hour block of English immersion. That was added by lawmakers later, partly in response to a lawsuit stating it wasn’t offering enough funding and instruction to ELL students.

But academic research and student data show it hasn’t worked for Arizona’s estimated 83,000 ELL students, roughly 5,000 of whom are in Tucson’s largest school district, TUSD, with an additional 3,500 at Sunnyside Unified School District.

A recent State Board of Education report found “significant deficiencies” in Arizona’s Structured English Immersion model. Citing a broad swath of academic literature on the topic, the report concluded that Arizona’s model segregates students “both physically and academically,” doesn’t allow access to rigorous courses, doesn’t provide teachers proper training, and is unrealistic in its goal of transitioning students into mainstream classrooms in one year.

In 2014, the latest year for which data is available, Arizona had the worst ELL graduation rates in the nation, at just 19 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

The Arizona Department of Education disputes those numbers, saying it’s an error in the way the state reports the data to the federal government. Instead, the Arizona Department of Education puts four-year graduation rates for students with limited English proficiency at 34 percent.

Either way, Arizona’s ELL graduation rates are low, and ELL students are way behind their English-speaking peers.

ELL students also consistently score far below their peers on standardized tests. Roughly 40 percent of Arizona students passed the AzMerit test in 2017. For students with limited English, 3 percent passed the language-arts portion of the test, and only 8 percent passed the math portion.

Some lawmakers already understood the varied problems with Arizona’s Structured English Immersion model and have tried unsuccessfully for years to address it.

But Boyer said the key to changing other hearts and minds at the Capitol has largely been talking about local control, parental choice and dollars and cents.

“With some members, (the pitch that worked) was we’re paying $424 bucks a kid, and there are 85,000 kids who are in this Structured English Immersion program. And every single year these kids don’t learn English, that’s an additional $35 million cost to the state per year,” he said.

Dual-language laws

repealed in 2006

Pam Betten, the chief academic officer at Sunnyside Unified School District, has been working with English-language learners since before the four-hour block requirement became law in 2006.

Back then, Sunnyside was in the vanguard of teaching non-native English speakers, with a successful, grant-funded dual-language program that was adopted as a model for other states.

“What we saw in the data then was kids would outscore our native English speakers on the standardized test of days gone by,” she said.

Julia Lindberg, an English language acquisition specialist in the Sunnyside district, remembers the early days of their dual-language program.

“It was so fun because you read about that stuff in the literature. The literature in bilingual education says kids who are in (dual-language) classes tend to outperform even English speakers on English tests. But to see it in reality, it was like, ‘Whoo, it really does work!’” Lindberg said.

There were other benefits. Students in dual-language courses were more likely to graduate. Dads became more involved with the academic life of students in dual-language programs, Betten said, though the district never could figure out why.

But state lawmakers, filling in the gaps of the English Only Proposition 203, repealed the dual-language laws in 2006. Sunnyside was able to work around the new laws for a few years but eventually had to shutter the dual-language program altogether, in favor of a four-hour block.

Betten said watching those ELL students’ test scores slide downward was heartbreaking.

“(The law) forced us to change that model that had been really successful for us,” she said.

And students don’t just suffer in English class. Because the four-hour block hinders students’ ability to take other classes like math and science, their test scores in other subjects plummeted as well, Betten said.

Dual-language programs still exist. Tucson Unified School District has successful dual-language tracks at Davis Bilingual Magnet School and Roskruge Bilingual K-8 Magnet School.

But under state law, students can enter dual-language programs only if they’re already orally proficient in English, or with a parent waiver for students over the age of 10.

Because students have to enter dual-language programs in kindergarten or first grade to truly absorb the knowledge and benefit from the program, the law makes it hard for schools to find enough Spanish speakers who are orally proficient in English at that age to populate the programs.

HB 2811, sponsored by Republican Rep. Jill Norgaard of Phoenix, would eliminate those requirements and ensure that the four-hour block doesn’t apply to students in dual-language programs.

SETBACK, NEW HOPE

In September, TUSD asked the State Board of Education for a waiver allowing students to opt into dual-language programs without meeting the language requirements. Board President Tim Carter said he was sympathetic to the district’s request, but after board members spoke with the board’s lawyer in executive session, they unanimously shot it down.

“Sometimes you want to take action on something, but it’s not something you have authority over or it’s not something the law allows you to do,” Carter said.

That was a setback for TUSD’s attempts to expand and replicate its dual-language programs. HB 2281, the pending legislation to allow students to opt into dual-language programs even if they’re not proficient in English, has given TUSD officials new hope.

And now, about a decade after the Sunnyside Unified School District shuttered its dual-language program, the district is trying to rebuild it.

Administrators are also encouraged by HB 2281, but they’re not putting all their eggs in that one basket, Betten said.

Instead, the district is starting with its preschoolers, since the English-only law doesn’t apply until kindergarten. Their hope is even if lawmakers don’t approve HB 2435, which cuts the four-hour block in half, the district can develop orally proficient preschoolers who can earn a waiver to enter the dual-language program as kindergarteners, and the program will grow naturally from there.

Of the two bills, though, Betten argues HB 2435 is probably more important to them.

“We have ELL students come at all grade levels, not just kindergarten and first grade. We have to have a model that works for students who come in fifth and sixth grade,” she said.

BETTER THAN

SUMMER SCHOOL

Surveying his students, Ramirez, the Sunnyside High School teacher, said he has no doubt many of them could be successful with a full course load of mainstream classes and only minimal support in an ELL class.

“I think instead of giving them an avenue to work out of the program, by requiring a four-hour block, it encourages them to stay. Because they’re all friends here, they all speak the same language, this is their safe space, this is their comfort zone,” he said.

The students pushed back, saying they didn’t want to be in the class and they’re trying to test out. But Franco, the senior who’s taking summer school classes to graduate, said he understood the urge to stay in the English Development class.

“They don’t want to talk English in other classes because some guy is going to laugh at how they talk,” he said.

Still, Franco would rather get over that fear than go to summer school.