PHOENIX – New pressure is building on Gov. Doug Ducey to reverse his defense of having monuments to the Confederacy on state-owned property.

In a letter Wednesday, James McPherson III, president of the board of the directors of the Arizona Preservation Foundation, reminded the governor of the calls in 2017 by many, including his organization, to remove the monuments following violence by white supremacists in Virginia.

“Unfortunately, nothing was done,” McPherson wrote.

Now, he told Ducey, it is time to finally deal with the issue “after yet another senseless killing of an African American and the subsequent nationwide demonstrations seeking the elimination of systemic racism and bigotry.”

But the foundation is aiming its ire at more than just the monument to Confederate soldiers, erected in the 1960s, that sits across the street from the state Capitol. McPherson also is demanding removal from state property:

People are also reading…

- A memorial to Confederate soldiers who fought for “independence and the constitutional right of self-government” that was erected about a decade ago in the state-run veterans cemetery in Sierra Vista;

- A plaque at Picacho Peak State Park, where the only Arizona battle of the Civil War was fought, dedicated to “Confederate frontiersmen who occupied Arizona Territory, Confederate State of America”

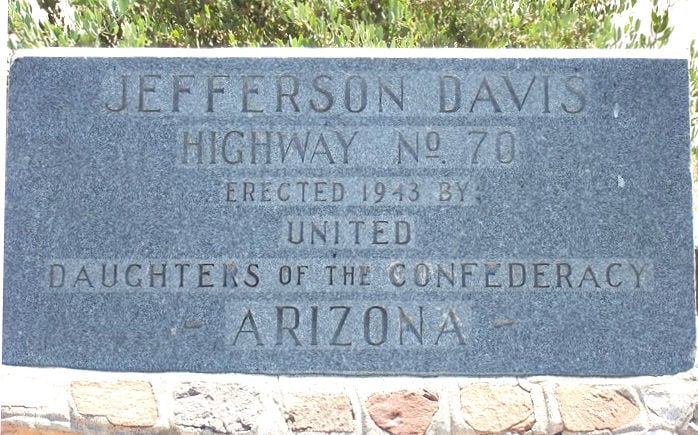

- A monument marking the “Jefferson Davis Highway” sitting adjacent to Route 60 east of Mesa, erected in 1943 by the Daughters of the Confederacy Arizona.

Ducey, when first asked about these in 2017, defended them as helping people “know our history.”

“I don’t think we should try to hide our history,” he said. “It’s not my desire or mission to tear down any monuments or memorials.”

But McPherson told Ducey on Wednesday that argument holds no water.

“The removal of these monuments will not ‘change’ history or ‘erase’ it,” he wrote. “What does change with such removals is what Arizona decides is worth of civic honor and recognition.”

Anyway, McPherson noted, it’s not like any of these were erected close to the time of the war.

It isn’t just the foundation pressuring the governor on the issue.

A separate letter to Ducey on Wednesday signed by 200 veterans issued a similar call, saying these monuments “dishonor and disrespect the service of those who swore and oath to ‘support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.’ ”

“Make no mistake, the Confederate soldiers honored by these monuments were domestic enemies fighting for the cause of slavery, leading to the loss of nearly 620,000 lives during the Civil War,” the letter states.

The closest Ducey has come to acknowledging the controversy has come over the monument in Wesley Bolin Plaza across from the Capitol, the one that was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy at the beginning of the civil rights movement in 1961. Asked last month about new calls to remove that in the wake of protests that followed the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, the only thing Ducey would say is that he did not want to make such a decision on his own.

“There is a public process to be able to put something into Wesley Bolin plaza or on state property,” the governor said. “I think there should be a public process if someone wants to go the alternative route.”

But it was Ducey who signed legislation in 2018 abolishing the Capitol Mall Commission that until then had the power to decide what went in — and what came out — of the plaza. That law now gives the power of removal exclusively to Andy Tobin, the governor’s hand-picked director of the Department of Administration.

And the other three monuments are under the purview of state agencies whose directors report to the governor.

On Wednesday, aides to Ducey refused to comment on McPherson’s letter or the whole issue of the monuments.

But it hasn’t just been the governor defending their presence.

Nicole Baker, spokeswoman for Wanda Wright, director of the Arizona Department of Veterans Services, said the monument in Sierra Vista is at the entrance to what she called a “cemetery within a cemetery.” These contain remains that originally were buried in the old military cemetery that served Fort Lowell in the late 1800s but were moved to Sierra Vista.

Baker said each of the tombstones is labeled “unknown” because of the lack of DNA to identify remains. But she said this section covers all who served in any fashion from the 1860s through the 1880s.

The stone marker in question was erected by the Confederate Secret Service Camp 1710, Sons of Confederate Veterans.

“While we can’t erase our nation’s history, we can certainly learn from it and help future generations plot the way forward,” Baker said.

McPherson has a different take.

“These monuments celebrate and promote bigotry and racism,” he wrote to Ducey. “They are devoid of true Arizona history and their very presence continues to hurt our African American friends, neighbors, coworkers, and strangers we may meet on the bus, at the lunch counter, or on a march for justice.”

The current controversy mirrors what happened three years ago when Rep. Reginald Bolding, D-Laveen, led the drive to remove Confederate monuments off state property.

“Any African American and many other individuals should not be required to use our taxpayer dollars to keep up with the upkeep and maintenance of these memorials,” he said at the time. Bolding said that would be comparable to having monuments on public lands to those who fought for the Nazis.

On Twitter: @azcapmedia.