The long-dead Santa Cruz River could flow again within two years.

Tucson Water, which had opposed the idea for years, unveiled a blueprint last week for putting heavily treated wastewater in the river through downtown Tucson. Officials call the plan “Agua Dulce,” Spanish for sweet water.

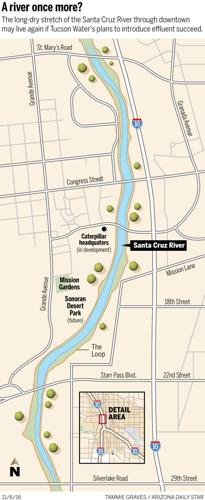

The idea would be to pump the effluent uphill from a sewage treatment plant northwest of the city via an existing pipeline south to 29th Street. From there, effluent would run downhill through the city’s core; the Santa Cruz flows south to north. Officials don’t know yet know how far downstream the water would run.

Similar plans have been proposed and discarded many times before, but the fact that the city’s water utility is pushing it for the first time could give it legs — particularly at a time when downtown is finally thriving.

People are also reading…

One of Tucson Water’s goals is to restore a stretch of the rich, natural riparian habitat that lined the river throughout much of the Tucson area until the mid-20th century. The utility also seeks to make the river a natural treasure that could generate tourism and economic development.

On a less glamorous front, it wants better control of some of the city’s effluent, which now runs downriver far from the city out of two sewage plants.

“This plan was 100 percent inspired by thoughts of Tucson and recasting a vision of what the Santa Cruz River through downtown should be in the future,” Tucson Water Director Tim Thomure said in an interview shortly after introducing the idea to a city water advisory committee Wednesday.

“I’d suggest a perennial flow of effluent supporting a stretch of riparian habitat is a better vision than supporting an empty channel.”

Trees, a “channel walk”

Thomure envisions a 20-foot-wide corridor of native trees including a 10-foot wide effluent strip. It would cost about $3 million to build outlet structures to transfer effluent from an existing sewer lines into the river, Tucson Water says. Operating the system would cost another $300,000 to $600,000 a year.

But Tucson Water says that’s far less money than it’s previously plan for the effluent: to treat it so it’s clean enough to drink.

Also in the new plan is a possible “channel walk,” or creation of an artificial channel running south from Cushing Street west of downtown to the historic Mission Garden at Mission Road and Mission Lane. There, residents have re-created part of the Spanish, colonial-walled garden that was in the original San Agustin Mission. Money for that would have to come from the private sector.

Thomure’s presentation to the Citizens Water Advisory Committee got an enthusiastic reaction. Tucson City Council members, environmentalists and a top official with the Rio Nuevo downtown redevelopment program were also enthusiastic after receiving earlier private briefings.

Jean McLain, associate director of the University of Arizona’s Water Resources Research Center and a city water advisory committee member, said Tucson Water's proposal "by supporting Tucson's citizens, environment and history . . . displays the best in modern water management." David Godlewski, co-chair of the business-backed Tucson Regional Water Council, said “it’s an idea worth looking at,” although it’s too early to tell if it’s feasible.

“I’m delighted and intrigued,” said Christina McVie, Tucson Audubon Society’s conservation chair. “While there are details still to be determined, I think it would be a win-win for the community.”

Before the City Council can formally consider the proposal, city staff must sell it to neighborhood leaders and business leaders.

Oft-squabbling city and county officials must also agree on a scheme to make the restoration compatible with the county’s plans to clear scores of existing native and non-native trees from the river channel in the name of flood control.

Finally, the city needs state approval of a plan to allow it to obtain just as many legal credits — which translates to earning just as much money — if it puts and keeps this water in the river as it would reap by taking it out and recharging it into the aquifer somewhere else. The credits allow the utility to pump the same amount of groundwater somewhere else, or it can sell them to someone else to pump groundwater.

Flows ended in 1940s

The death of the Santa Cruz is Tucson’s longest-running urban tragedy.

The river, which starts in the San Rafael Valley north of Mexico and dips south into Mexico before heading north through Nogales, Tubac and Green Valley into Tucson, was never a year-round stream throughout its length. But nine separate stretches, some quite long, carried water year-round at turn of the 20th century. The rest carried water only when it rained.

But due at least in part to massive groundwater pumping that lowered the water table, no section of river has carried even intermittent, natural water flow since the 1940s. A huge mesquite bosque that once drew naturalists from across the U.S. was killed off by groundwater pumping and by people clearing the trees for fuel.

By the mid 1970s, the only sections of river that carried water when it wasn’t flooding were those downstream of sewage-treatment plants in Nogales and in suburban areas northwest of Tucson.

Off and on since the 1990s, various officials have talked of reintroducing water into the Santa Cruz. Some early blueprints for the Rio Nuevo project proposed a “River of Blue.” That became part of the Rio Nuevo master plan, approved by the City Council in 2001.

The Army Corps of Engineers studied the idea in the early 2000s, but rejected it as too costly. The Corps proposed instead planting hundreds of acres of mesquites and shrubs and a smaller batch of cottonwoods. But federal funding was obtained only for a fraction of that proposal, for a stretch of river between Ajo Way and 29th Street.

As recently as two years ago, some city and Rio Nuevo officials again talked about reintroducing water into the Santa Cruz. Tucson Water officials objected, saying again it would cost too much and would risk groundwater contamination if the effluent were to leach out pollutants from an 85-acre landfill in the heart of the west side Rio Nuevo area.

Why now?

What changed the utility’s mind?

First, Thomure noted, it’s been 30 years since the water utility started developing pipelines that send reclaimed water to parks, schools and golf courses.

“The current system is now built out,” he said. “We’ve reached virtually all potential large users.”

Second, due to intensive water conservation in Tucson over the past decade, the utility no longer sees a short-term need to build a major system to treat wastewater for drinking. As recently as two years ago, the utility planned to start construction on a full-scale wastewater recycling plant by the early 2020s.

Now, if the reclaimed water is ever needed for drinking, it will still be available and closer to the city’s residential core when it’s in the downtown area, he said.

Thomure, who started as utility director in January, said the utility also heard from environmental activists who favor the idea. Also, a plan to put the effluent into the river is much more aligned with policy decisions the City Council has made on water issues over the years, he said.

The city’s history of having dried up the river made the utility open to putting effluent back in, he said. With the raising of the city’s underground aquifer in recent years due to its use of Colorado River water, he said, “We felt that if there was now an opportunity to go back and restore stretches of the river, we should be open to that.”

“A tourist draw”

Fletcher McCusker, Rio Nuevo’s board chairman, is enthusiastic about the idea.

“We introduced the notion of creating some sort of trickle in Santa Cruz four years ago and got nowhere with it,” he said. “We met with city water and they thought it was heresy.”

The current leadership, the city manager and Tucson Water are more visionary, McCusker said.

“This can help recharge the aquifer and create a tourist draw,” he said “It has appeal. The pipelines are already in place. It’s just a matter of making a decision.”

Placido Dos Santos, a water-advisory committee member, called the idea “the most exciting thing I’ve ever heard” at committee meetings. The outlet where effluent would go into the river would be an ideal place to build an educational or recreational center about water, he said.

“Don’t forget the word recreational,” he said. “Kids need to be able to play.”

Committee member Chuck Freitas said the idea has merit, but said Tucson Water ratepayers shouldn’t be required to pay for all of it because it benefits to the entire community. He said it’s not fair to compare its cost to that of treating wastewater for drinking, since “no one has talked to the public about the costs of the potable water reuse. They don’t know what those costs are.”

Mayor Jonathan Rothschild and Councilmembers Paul Cunningham, Karin Uhlich and Steve Kozachik also had high praise for the idea.

Maintenance work

Two years ago, when Tucson Water officials opposed putting effluent into the river, Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry was an enthusiastic backer of the idea and dismissed the water utility’s concerns about the landfills as “bogus.”

Last week, Huckelberry was much more guarded, saying he still thinks the idea is “fine,” but he cautioned that if the effluent creates a riparian corridor, it must be managed regularly to prevent flooding.

Pima County, for instance, is preparing to clear much of the existing vegetation from the riverbed as well as a good deal of sediment to reduce the chances of floodwaters climbing out of the river . That’s going to cost $1 million to $2 million and is probably not going to be popular, “but it has to be done.”

As an alternative, the city might consider planting lots more trees on top of the river banks and irrigating them heavily to avoid the heavy maintenance costs of clearing the river channel, he said.

“If you are growing stuff in the river, and you get a big flood flow, it probably will all get washed out anyway,” he said.

Thomure said he thinks the city is up to the task of keeping the stream maintained — once the county has cleared out the excess sediment to restore the river’s capacity to carry floods.

“Once we deploy our effluent and create riparian habitat, we will do more frequent, minor maintenance,” he said.