Frozen but alive inside a laboratory at the University of Arizona is a potential vaccine against an insidious, incurable, sometimes fatal respiratory disease.

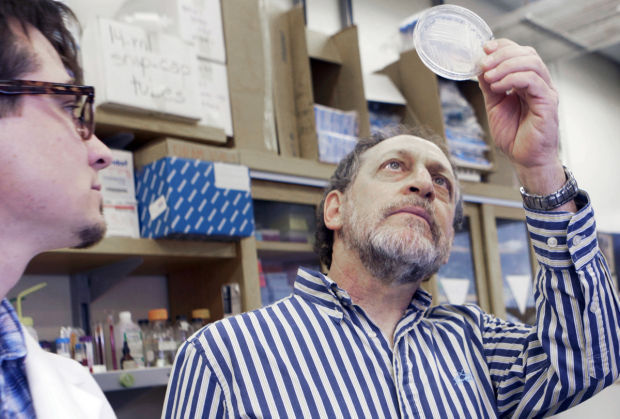

The live vaccine, invented by UA fungal geneticist Marc Orbach, has already protected mice from valley fever.

Orbach achieved the feat by removing one gene from the valley-fever fungus and creating a mutant spore that seems unable to cause disease, and only to protect from it.

Nearly 6,000 human valley fever cases were reported in the state last year, making it one of the most commonly reported infectious diseases in Arizona. So far this year, 519 human cases have been reported to the state, including 108 in Pima County. There is no proven way to prevent it other than not visiting or residing in places like Tucson, where the valley fever-causing coccidioides fungus lives.

People are also reading…

About two-thirds of the valley fever cases reported annually in the U.S. occur in Arizona. Some researchers believe that as many as 30,000 human cases of valley fever occur in Arizona each year, but that many of them go undiagnosed. Approximately 60,000 Arizona dogs also get sick annually.

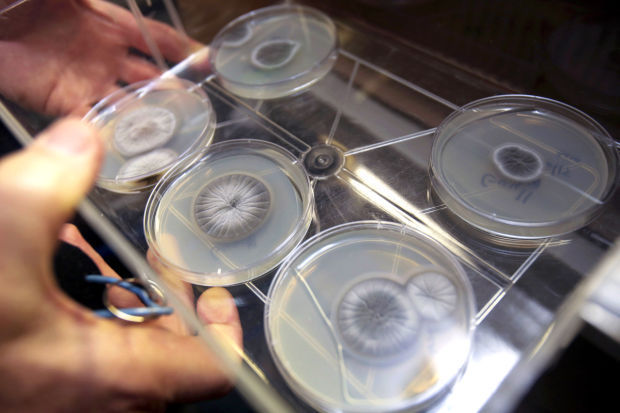

Delta-CPS1, as the live vaccine is called, might protect both dogs and humans. And because it can be grown and harvested in a lab, it costs far less than the $40 million assigned to a previous attempt at a valley-fever vaccine that would have used fancy and pricey technology to get the gene out of the fungus and put it in another organism, like a yeast or bacteria, to make a protein antigen.

There’s no expensive protein purification step with delta-CPS1 because the vaccine is the spore. The research and development cost is estimated at $2 million or less.

Still, the UA research team has hit financial and political barriers to getting the vaccine from invention to clinical trials. Since valley fever is primarily a regional disease, it’s difficult to get national funding for it. The research team recently applied for a state grant through the Biomedical Research and Education Foundation of Southern Arizona, but was turned down. Now they are appealing to Arizonans to help.

UA researchers are further along on a promising cure for valley fever (see accompanying story), but they say a vaccine would prevent the organism from ever doing any damage, which is particularly important in people with compromised immune systems. Also, valley fever is so often misdiagnosed, or diagnosed late in the illness, that many patients and dog owners consider prevention to be critical.

But for now there’s no timeline of when, if ever, a valley-fever vaccine will be available.

Just one breath

The main risk factor for valley fever is basic, and, for Tucsonans, impossible to avoid. It’s breathing air in one of the areas in the Southwest and West where the disease is endemic — primarily Arizona and the San Joaquin Valley area of California. Valley fever has also been found in Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, parts of Mexico, and in parts of Central and South America.

According to current research, one of every three people who inhales a coccidioides fungal spore gets sick enough to go to a doctor. In one of every 200 people who get sick, the valley fever disease disseminates, meaning it goes to the bloodstream.

One published study indicated that an average of about 160 people a year had death certificates that listed the cause of death as coccidioidomycosis, which is valley fever. Some of those people die because they aren’t diagnosed until they are very ill, but others just have severe infections.

Dr. John Galgiani, a physician who is director of the UA’s Valley Fever Center for Excellence, and Orbach, a professor in the UA’s School of Plant Sciences, are part of the UA team developing delta-CPS1. A third key member is Dr. Lisa Shubitz, an associate professor in the UA’s School of Animal and Comparative Biomedical Sciences.

The odds of getting sick from valley fever are worse for dogs than for humans. Most dogs don’t have to die of valley fever anymore, but they are sometimes euthanized because their owners can’t afford the expensive medications.

For an uncomplicated case of valley fever in a dog, owners spend at least $2,000 on diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up, estimates Shubitz, whose veterinary practice specializes in treating dogs with the disease.

Live vaccine

There have been at least two other serious attempts to get a valley-fever vaccine to market, the most recent a collaboration of five universities, including the UA.

The first resulted in sore arms but no conclusive proof that it worked. The second attempt was a laboratory-created hybrid protein vaccine made in a yeast strain using the DNA from the valley-fever fungus. It looked promising, but stalled due to cost.

“It was a very, very cool vaccine,” Galgiani said. “The problem is, to go from that point of discovery to actually starting a human, clinical trial was on the order of $40 million. Nobody had that.”

Orbach invented delta-CPS1 after reviewing work by a researcher at Cornell University. That researcher had identified an important virulence factor for a plant pathogen of corn. Both plant and animal pathogens have virulence factors that are required for infecting their host.

The Cornell researcher found one gene in the fungus that was responsible for damaging the corn plants. Orbach found a similar gene in the valley-fever fungus was important for the virulence of the valley-fever fungus. By slicing out the gene, he created a mutant spore.

“Our thought is that by putting the mutant in, you have no risk of getting disease,” Orbach said. “You want something to go into the host that won’t survive but will induce the immune system to protect the host from another infection.”

Using that mutant spore, Orbach was able to create a live, attenuated vaccine. The risk of using a live vaccine is that the person gets sick with the disease the vaccine is trying to prevent. And that was a huge concern for Galgiani. But he says the safety data so far is impressive.

“I’m pretty comfortable with the idea that it’s a viable vaccine candidate to go into clinical trials,” he said.

When Shubitz did the testing, the mice that received the mutant-spore vaccine followed by challenging their lungs with lethal doses of wild spores that cause valley-fever infection stayed healthy. But the mice that received only wild spores without the vaccine all died.

The overall survival rate is more than 95 percent.

“It’s better than anything I’ve worked with in the 16 years I’ve been doing this,” Shubitz said.

Funds scarce

While valley fever is common in Arizona and California, it isn’t in other parts of the country and the world. A lack of need worldwide or even nationally makes funding a vaccine less enticing for drug companies.

Valley fever is what’s known as an “orphan disease,” meaning fewer than 200,000 U.S. residents have it at any given time. But since two-thirds of sufferers are from Arizona, there is a big local interest in both a prevention and a cure.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh, the market is huge — it’s California and Arizona,’” Galgiani said. “But not all of California is in the valley-fever zone. Suddenly you start realizing that to be commercially enticing, you need to be talking about a huge market. Two states is not even close to big enough.”

In order to get the vaccine to market, the researchers need to prove it is safe. If they can do that, a vaccine against even a small orphan disease like valley fever could probably get commercialized, Galgiani said.

But that takes money — at least $200,000, and possibly as much as $2 million, the researchers say.

The team is now doing what it can at a community grassroots level, beginning with dog owners in what’s known as the valley-fever corridor — Maricopa, Pinal and Pima counties.

“A lack of funds has literally held this project to nothing for the last two years. We know we have to write grants and do social-media fundraising. But we have a learning curve here — social-media-based fundraising is a new thing for us,” Shubitz said.

Though she is more accustomed to microscopes and mice than social media, Shubitz was relatively successful with a recent online fundraising campaign, considering that it had little publicity.

The project received $20,000 from a southeastern Arizona dog breeder who said she’s seen too many dogs get severely ill from valley fever. It also received nearly $5,000 — $25 to $100 at a time — from dog owners across the Southwest. In addition, local kennel clubs also made donations of several hundred to $1,000, and local dog business Sit! Stay! Play! holds an annual fundraiser that donates to the cause.

Next up, the team may try to find a business partner and submit an application for a small-business grant.

In the meantime, people and pets are suffering.

“It’s called the valley of death, between discovery and getting it to clinical trials, or getting it to market,” Galgiani said. “This is considered intellectual property. A patent application was filed. This is something brand new ... to get the work done is sort of putting bricks and mortar together, figuring out how good it is, measuring it in eventual clinical trials.”

Low expectations

Patients with valley fever want to be excited about a vaccine. But they have been excited about prevention and possible cures before, only to be disappointed.

“I would say people are hopeful about a vaccine, but no one is holding their breath,” said Washington state resident David Filip, who started a support group called Valley Fever Survivor with his mother, Sharon Filip, after she nearly died from valley fever following a visit to Tucson in 2001.

The group has grown to 1,600 on its closed Facebook page and also maintains a website at valleyfeversurvivor.com online.

The Filips say that while their group talks about treatments and prevention, it is mostly about giving one another support that isn’t always available in families and communities due to a lack of understanding about valley fever.

That cautious optimism is wise, because the vaccine isn’t coming any time soon.

“It took at least 15 or 20 years for the polio vaccine, and we are still looking for an AIDS vaccine,” said Dr. Raymond Woosley, founder and president emeritus of the Tucson-based Critical Path Institute, a partnership with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that aims to improve the drug development and regulatory process. “Valley fever is an orphan illness, and it’s very hard to develop a vaccine for massive illnesses, much less orphan.”

Even if a vaccine hit the market tomorrow, it wouldn’t help current patients like Benson resident Cynthia Drummond, 48. But Drummond says she’d make sure that everyone she loves is inoculated.

“It’s definitely something that needs to happen. I don’t want anyone else I know to get this sick,” Drummond said. “I don’t get sick; nothing ever stops me. But this has stopped me dead in my tracks.”