Three men in orange jumpsuits presented the U.S. and Arizona flags with military precision under the watchful eye and terse commands of a prison guard.

The inmates who presented the flags on a recent morning are among 113 veterans at the Arizona State Prison Complex on South Wilmot Road participating in the Arizona Department of Corrections’ new “Regaining Honor” program.

The program was launched in December to instill discipline and a sense of camaraderie among veterans at the prison, officials said.

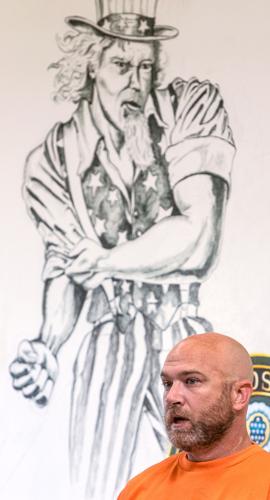

Tanner Sanders, 36, spent 12 years in the Navy boarding ships in the Persian Gulf to catch pirates and contraband traffickers.

He was convicted last year of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon for chasing young troublemakers who were breaking windows and turning over trash cans in his neighborhood.

People are also reading…

Sanders attends classes with other veterans in the Regaining Honor program “basically from sunup to sundown” five days a week.

As a result of the program, “I’ve noticed myself hanging my head a little bit higher,” Sanders said.

“The fear of what to do when I get out has been alleviated somewhat,” Sanders said, noting many veterans end up homeless after leaving prison.

Inmates are eligible for the program if they are classified as minimum custody, received an honorable, general or medical discharge from the military, and are less than two years from being released.

The state prison system houses about 2,700 inmates who are veterans, officials said, including 267 inmates who meet the program requirements. Another 1,850 veterans work for the prison system.

The inmates in the program, which is voluntary, do not receive special treatment, said Deputy Warden Dionne Martinez.

“If anything, they will be held to the highest standards,” Martinez said.

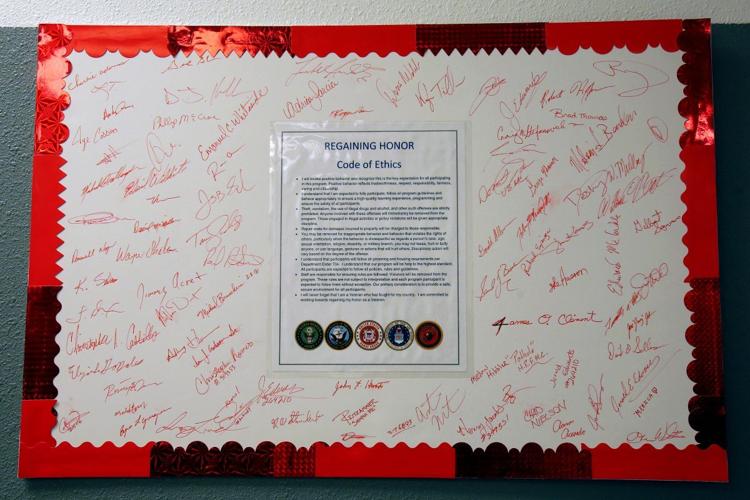

The program includes a strict code of conduct and classes on drug addiction and re-entering society that are tailored for veterans, she said.

As the program gets up and running, a physical training regimen and community improvement projects, such as gardening, will be added, she said.

All of the program participants live in the Whetstone Unit, a large room where inmates watched “Modern Family” and other television shows from their single beds and chatted with each other.

The grouping of the veterans in the unit allows the Department of Corrections to coordinate with veterans services organizations, officials said.

The housing unit also is “a reflection of the military pride that is instilled in our veterans,” Martinez said.

The program grew out of a discussion last year between the state prison director and members of the veterans caucus at the Legislature who wanted to help veterans in prison, said Karen Hellman, administrator of counseling and treatment services at state prisons.

The goal is to expand the program to prisons throughout the state, including 50 women veterans at the Perryville prison by the end of the year, Hellman said.

Emanuel Whiteside, 66, served in the Army during the war in Vietnam.

He fell under the influence of drugs and alcohol, which he said is the underlying reason many of the veterans in the program are in prison.

“That is it. That is why we’re in here,” Whiteside said.

He was arrested for a DUI in a car police said was stolen, but which he says was legally bought and registered.

Whiteside said he is trying to get as much as possible out of the program.

“You’ve got to reach down into yourself and look to a higher power,” he said.

His main concern is finding a job after he is released so he can “stop taking and start giving” to his family, who suffer alongside him while he is in prison.

“Our families are in prison, too,” Whiteside said.

Tye Casson, 37, spent two years as a Navy corpsman working in a hospital.

“Once upon a time, my core beliefs were honor, courage and commitment,” he said. But after his medical discharge, “I changed my values from honor to drugs.”

“Every day you wake up with the fact, ‘Hey, you know what? I put myself here,’” Casson said. “My core beliefs somehow got flawed along the way.”

With the Regaining Honor program, Casson said he can channel his thoughts in a positive way that helps him support those around him.

“I am so encouraged by this program,” Casson said, adding the big question for him now is, “How am I going to make the world a better place for my daughter?”

Nate Dixon, 34, was a medic in the Army for six years. Like Whiteside, he became addicted to drugs and was convicted of drug trafficking.

Through the program, he found out about his eligibility for medical benefits through the VA.

He also takes AA classes and picked up “some good tips” from a money management class.

“I’m terrified about getting out and not being able to get a job,” Dixon said, noting he will have a hard time finding a job in the health-care industry, where he used to work.

The Regaining Honor program is “still in its infancy,” he said. “I’m looking forward to seeing what they have planned.”

Contact Curt Prendergast at 573-4224 or cprendergast@tucson.com.