Ansel Easton Adams’ iconic photographs of the American West that changed perceptions of the wilderness and photography are popular, recognizable subjects of coffee-table books, calendars, posters and postcards.

Rebecca A. Senf wants viewers to “look at his work beyond coffee-table books and calendars.”

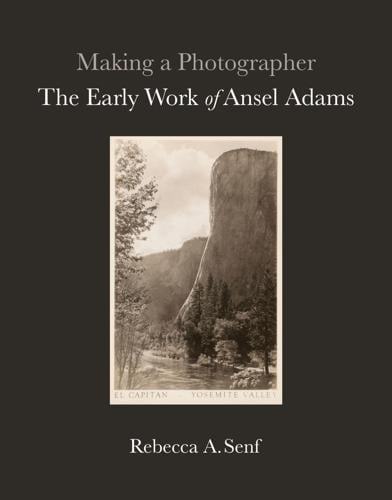

Presenting a nuanced, textured sense of who Adams (1902–1984) was and what he accomplished are among the goals of “Making a Photographer: The Early Work of Ansel Adams,” a recently released book written by Senf, chief curator at the University of Arizona Center for Creative Photography, and a companion exhibit, “Ansel Adams: Signature Style,” which opens Saturday, Feb. 29, at the CCP, 1030 N. Olive Road, in the UA fine-arts complex.

The book and exhibit, which examine the early career and artistic evolution of the acclaimed photographer, are focal points of the annual family-friendly Adams’ birthday bash set for noon-4 p.m. Saturday at the CCP.

BOOK IT

“Making a Photographer” is the first monograph dedicated to the beginnings of Adams’ career and is the first new academic work published on Adams in almost 20 years.

The glossy 288-page biographical book is packed with 177 images that give an “I never knew that” perspective of the renowned photographer.

It’s an “approachable, accessible, readable book,” says Senf. “I want people to understand who Ansel Adams was.”

Senf, who grew up in Tucson and received her bachelor’s degree in art history from the UA in 1994, first took a deep dive into Adams’ work in 2003 while researching an exhibition and publication for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Her doctoral dissertation, completed in 2007, was on Adams.

Unencumbered by a preset lens of shoulds and expectations, Senf approached the book project as a scholar without a hypothesis.

Using the center’s extensive Adams archival collection as the primary source, she scoured original documents like contracts, letters, promotional materials, unpublished writings and grant applications. Adams co-founded the CCP in 1975 with John P. Schaefer, then UA president. Adams’ was one of five inaugural archives, which includes more than 2,500 fine prints.

The book gives an unprecedented view of the photographer, who snapped his first photos of Yosemite Valley while on a family vacation in June 1916.

An only child who was home-schooled, Adams was planning to be a concert pianist, says Senf. Adams, then 14, photographed waterfalls, mountains and rocks with a Kodak Box Brownie camera. When he returned home to San Francisco, he created an album of 109 commercially printed photos.

In those first snapshots, Senf says you can see the buds of Adams’ thoughtful experiments with elements such as light and composition. For example, five shots from 1916 photo album show Adams exploring the use of foreground elements and placing Half Dome in different positions within the photo frame.

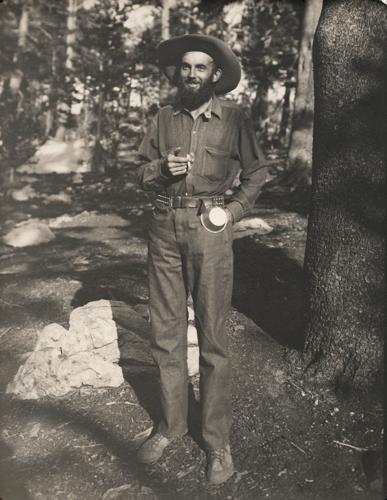

After a few more trips to Yosemite, Adams joined the Sierra Club, got a job as a lodge custodian living on the valley floor and became an accomplished mountaineer and a notable photographer.

Senf traces Adams’ trajectory and stylistic evolution, evident in his work for the Sierra Club and in Western sites like New Mexico and the High Sierras. Adams originally used a soft, painterly approach to photography that he replaced with his familiar crisp, contrasting, sharp-focus style.

Adams was aware of his audience and continually learned, modified and sharpened his technique and skills. He aimed to convey his intent to his audience, says Senf.

Many of Adams’ photos from Yosemite National Park were created as a part of a public-relations campaign. Commissioned in 1931 by Yosemite Park and Curry Co., the park concessionaire, Adams reported to the marketing department and was strategic with his images, says Senf. Photos were exacting, precise and what was needed to communicate the intended message of promoting the park visitation.

Adams negotiated a contract in which he was paid less, but he retained the negatives, she says. The relationship blew up when the Curry Co. published a book, “The Four Seasons in Yosemite,” unbeknownst to Adams, who found the book in a gift shop. Adams sued as his contract specified royalties.

The last chapter in Adams’ stylistic evolution began in 1941 when he was hired by the Department of the Interior to take photographs of the national parks as part of a mural project for the Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C. When funding was yanked during World War II, he pursued Guggenheim fellowships to continue the work.

ON EXHIBIT

An album consisting of photos taken by 14-year-old Adamswill be among the items on exhibit in “Ansel Adams: Signature Style,” which opens Saturday and continues through June 20.

The exhibition, a “distilled visual experience” of the book, includes 30 pieces on the wall and numerous albums and published pieces in cases, says Senf. The exhibit shares three elements in Adams’ body of work: his signature style, the shift in style in 1941, and his commercial work.

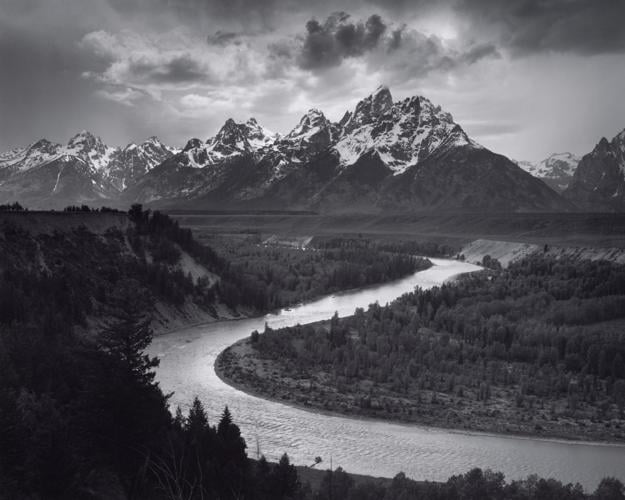

Photos illustrating the contrasting ends of Adams’ style spectrum as well as photos that “grab you by the shirt,” like the 1943 “The Tetons and the Snake River,” will be in the exhibition, says Senf.

Senf says she hopes the book and exhibit are thought-provoking and inspire discussion and questions like “where does excellence come from?” and “why do we like his work?”