Editor's note: David Maraniss has since cancelled his appearance at the Tucson Festival of Books.

While his father Elliott was alive, prize-winning journalist David Maraniss never asked him or his mother Mary about how or why he was blacklisted from his journalism profession for five years in the 1950s because of a Communist past.

“It was a shadow in our family,” recalled two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Maraniss, author of 12 books, a visiting political science professor at Vanderbilt University and an associate editor at the Washington Post. “It wasn’t really discussed.”

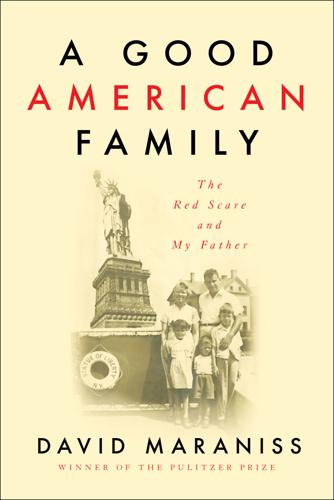

Now, in “A Good American Family,” Maraniss, who speaks Sunday, March 15, at the Tucson Festival of Books, lifts the veil. His book opens a window into a small corner of what some feel was one of the darkest chapters in U.S. history: the Red Scare that morphed legitimate fears of a foreign ideology into a climate that led to persecution of Maraniss’ father and many other U.S. citizens.

The book is not just about what generated his parents’ longtime affinity for Communism and Elliott Maraniss’ subsequent blacklisting, but of how these events and those surrounding them embodied a bigger question: What did it mean to be a good American?

Elliott Maraniss served four years in World War II, including the climactic Okinawa battle in Japan. He was, his son wrote, a booster of Middle American sensibilities: “of Big Ten universities and glacier lakes with swimming beaches and dairy farmers and black earth and corn on the cob and Tigers or Cubs or White Sox or Braves games on the radio.”

He was a highly regarded rewrite man and copy reader for the now-defunct Detroit Times in the late 1940s and early 1950s. But in February 1952, on the day that the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) subpoenaed Elliott Maraniss after an FBI informant named him as a Communist, his supervisors fired him on the spot.

His Communist sympathies dated to the late 1930s, when he penned leftist editorials for the University of Michigan Daily. And he brooked little deviation from Soviet orthodoxy back then.

When Hitler and Stalin signed the infamous Nazi-Soviet nonaggression pact on the eve of World War II, Elliott Maraniss and his future wife, Mary Cummins, switched overnight from crusading anti-fascists to pacifists, caring little about fighting fascism until Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. They stayed Communist after the Iron Curtain descended on Eastern Europe after the war.

After his firing, Elliott Maraniss could find no steady, secure work in journalism until 1957, when the Madison Capital Times, one of the few U.S. newspapers to fight the political persecutions of the McCarthy era, hired him as an editor. There, he rose to executive editor, and lived a generally happy, successful professional and personal life thereafter. By then, his politics had already shifted to a more conventional form of liberalism.

Maraniss’ book asks whether his father was a good American in standing up for the Fifth Amendment, in refusing to answer questions about his past from the HUAC. But Maraniss also asks, was House committee Chairman John Wood a good American because he sought to root out Communists and fellow travelers? Even though the ex-Ku Klux Klansman Wood stood firmly behind his native Georgia’s Jim Crow tradition, fighting off all efforts to pass anti-lynching laws and ban legal segregation?

Here, Maraniss answers questions about his book:

Question: Your father has been dead since 2004 and your mother, since 2006. What made you write this book now?

Answer: I started it five years ago, in the spring of 2015. It was a book that was sort of in the back of my mind for a long time. I knew I would not write it while my parents were still alive. It was a subject that was not a matter of embarrassment for my family, but it was something my father didn’t talk about.

Q: Was it hard to write about a past that your father shunned?

A: Even when I started it, I had to sort of deal with the issue if my father didn’t want to talk about it, why am I writing about it? I realized I wanted to search for the truth to understand my family. That was important. I knew that at some point I would want to explore that subject. I’d written many biographies of people who were strangers to me when I started but I became so familiar with them that I knew more about their families than they did — Roberto Clemente, Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Vince Lombardi. I realized I hadn’t done that with my family. I realized there was a pivotal time of my family’s existence. I wanted to explore what really happened.

Q: Did you not talk about this with your father because you didn’t want to rock the boat?

A: It’s not a matter of rocking the boat. It was a matter of not upsetting my father needlessly. What was the point of bringing it up? As a matter of fact, since the book came out, I’ve gotten hundreds of emails and letters from people whose who families endured something like this and thanked me for going back finding out what really happened. It’s something they didn’t do and they’re now interested in doing.

Q: What obstacles did you face researching this book?

A: The most difficult obstacle was more psychological than physical. It was being willing to confront aspects of my parents’ earlier existence that might be hard for me to reconcile. I loved them. I knew they were motivated by idealism. (But) there were points when I would shake my head and say what were you thinking?

Q: You mean the attachment to Communism?

A: It wasn’t the fact that he was a Communist. I understand that he was motivated by idealism, the rise of fascism and Nazism in Europe. It was the context of the times, the failures of capitalism during the Great Depression. I was boggled by how he could support the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939 and the Soviet invasion of Finland. The rationalizations he would use in his editorials were really well written but misguided.

Q: But he changed his mind later, winding up as a liberal.

A: By the time I reached the age of real political consciousness, in my teenage years, he taught me never to fall for any rigid ideology and to search for the truth wherever it took me.

Q: What did the Detroit Times know about your father’s Communist background before firing him?

A: The subpoena doesn’t say anything; it just says you have to appear before this committee. That was enough.

Q: Was the paper wrong in firing him?

A: To answer that, go to Chapter 24 and read his statement to the committee. He said, “I view this attempt to muzzle me and drive me off my job as a direct attack on freedom of the press and the right of newspapermen to participate freely in the political life of the country without fear of reprisal.”

Q: But even if it hadn’t been with the Communist Party, doesn’t any form of political activity violate a basic journalistic ethic?

A: If I had done the same thing, and I said it in the book, I would have been fired from the Washington Post.

Q: Are there parallels today to the era of HUAC? Our president calls the press enemies of the people, fires dissenting staffers and knocks critics as traitors. Are we heading into another round of blacklisting?

A: History doesn’t repeat itself precisely, but certain elements echo through the years. One is what does it mean to be an American. Today’s parallel is make America great again. Whose America? Make America great for white males? Is that the definition of what an American is? In World War II, we fought against the demonization of certain groups for political purposes. Today that is evident with the dehumanization of Muslim and Latino immigrants.