NOGALES, SONORA — They tear sofas apart for the metal, burn Christmas lights for the copper and salvage old plastic toys.

They work fast to dodge bulldozers that load trash into semitrucks for a one-way trip to the landfill.

Slogging through knee-deep muck, they grab whatever they can: bottles, boxes, clothes. Most precious is copper, which can sell for about $4 a kilo, roughly 2 pounds — nearly 10 times as much as paper.

They sort what they collect and wait for the next pickup or municipal garbage truck to grind its way up the dusty road to the dump.

If they’re lucky and they had a good day or a driver gives them some meat, they light a fire and cook it up.

When there’s nothing to do, they sit on discarded furniture or use old boxes to shield themselves from sun and rain.

Waste pickers can live their entire lives at el Tirabichi, as the locals call it.

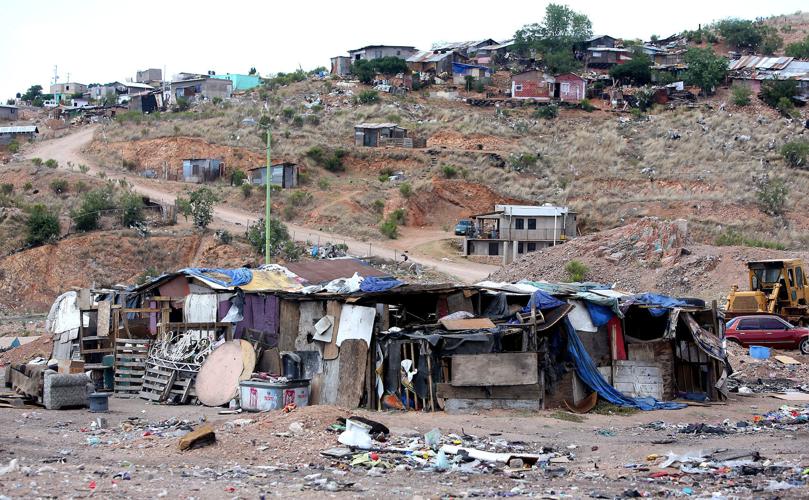

Some live in houses local charities or church groups help them build on the hillside above the dump. Some live in tiny, mostly unfurnished homes made from cardboard, wood, tarp — discarded materials they find as they work. If they don’t find mattresses, they make beds out of old clothes.

El Tirabichi is supposed to close by the end of June, prompted by a fire that ripped through in March and killed a man. The city will contract a private waste management company and most dump trucks will go to a newer transfer station and to the landfill on the other side of town.

But some city trucks and private cars keep making their way here and dumping their loads. And waste pickers continue showing up and making their piles.

They don’t see a choice.

Many of them came here after being deported, dropped off at the border without a peso in their pocket. Some are drug addicts hoping to sell enough to finance their next fix. Some are parents, scavenging to feed their children.

El Tirabichi is a refuge for the desperate.

A waste picker carries a sheet filled with recyclables to sell to Heidi Figueroa, who buys from other pickers and resells items to support herself and her seven children.

•••

El Tirabichi opened in the 1990s in the Pueblo Nuevo neighborhood, about five miles from the border.

As trash began to pile up, so did the makeshift structures the pepenadores, or waste pickers, call home. At its peak, there were about 60 homes here. Now there are fewer than a dozen, many burned in recent fires.

The dump site used to be far from town, but Nogales has grown so much that now it’s in the middle of the city. A hospital is soon to open about a half-mile down the road — another reason the government says el Tirabichi needs to go.

“The transfer station is not officially a landfill, but it has become an open dump site,” says Claudia Gil, who leads the city’s institute for research and planning.

It’s not safe for the waste pickers or for the people who live nearby, she says.

Most waste pickers work long days, starting before 6 a.m. They use their bare hands, drink from a large water basin that is often dirty, and at times eat what they scavenge.

Kids run around with unrelenting coughs.

But the pickers don’t mind. Without el Tirabichi they’ll be out of a job — and for some, a home. Many lack birth certificates or other forms of identification. Most only finished elementary school.

Their employment options are limited. But as in other parts of the world, they’ve started to organize.

Instead of closing the dump, they say, the government should distribute protective gear and gloves, and make it safer.

In Brazil, for example, waste picking is recognized as an occupation, and organizations can be contracted to work. In Colombia, the government provides infrastructure and equipment while waste pickers provide labor.

Nogales could have a designated area in the landfill where waste pickers work directly for the city and the waste management contractor, says Gil, of the city of Nogales. Perhaps they could recycle straight from the source.

City officials are working with about 50 waste pickers to help form a co-op or microenterprise, Gil says. But there’s a lot of mistrust of the government.

“We want work! We want justice!” the waste pickers chant as they march through the city’s center for International Workers’ Day, holding a banner and a coffin representing the pepenador who died in the March fire only months after being deported from Phoenix.

•••

Hugo Diaz set up a mattress for shelter from the harsh sun and sits among items he scavenged. Diaz has lived at the dump for over a year. His pile on the right was collected in one day. He said it could sell for about $30.

Hugo Diaz, a 30-year-old from the southern state of Chiapas, is startled out of a midafternoon nap by the sound of excitement. A truck is coming, and a group of mostly young men lead it to the dump as others run to catch up.

They hop on the back of the still-moving pickup and start to scavenge paper and plastic bottles before it rolls to a stop.

After Diaz tosses bottles and cardboard out of the truck, he uses an old pink comforter to drag his finds back to his pile.

There are unspoken rules in el Tirabichi.

Rule No. 1: Whatever you grab from the truck is yours.

Rule No. 2: When a city dump truck backs up and empties hundreds of pounds of garbage, everyone gathers around it before tearing through the plastic bags to see what is salvageable.

But the rules are not always followed. Pickers can’t leave anything unattended, especially overnight.

Diaz, who arrived about a year ago and lost his home in the March fire, now sleeps next to his pile, where he keeps a mattress and a discarded armchair.

Nearby, on an old couch under one of the few trees at the dump site, is Martin Lizarraga, 47, who once spent three months working in the onion fields in Chandler.

“Over there, they separate everything, not like here,” he tells Diaz.

The dump in Nogales should be more like those in the United States, he says.

Lizarraga has followed the city’s dump from one location to another for more than 30 years. But he’s tired of always being dirty, of the dead dogs they occasionally find inside loads.

Most of el Tirabichi’s waste pickers are not from Nogales. They come from neighboring Sinaloa or southern Mexico. Some were on their way to the U.S. but never made it. Others were deported after work raids or felony convictions.

Perpetuo Corredor walks around with a pair of broken binoculars hanging from his neck, and his dog, Canela, on a leash. The binoculars, he says, help him peer across the border and think of the daughter he hasn’t seen since he was deported eight years ago after a jail stint for selling crack cocaine.

Oscar Galvez worked in the fields of Kern County, California, for nearly a decade when he was arrested during a work raid and sent back.

Sometimes he misses the United States, he says, “but we are not from over there.”

He sits by the fire while his friend Juan Carlos Ramos fries up pork rinds and chicken wings a truck driver gave them.

Ramos spots a chicken breast cooking in the midst and calls dibs with a wide smile.

They all take turns cooking, but everyone agrees Ramos is the best.

They wash down the meal with hot chocolate, the powder mixed in tin cans and plastic soda bottles.

Today dinner is served after the sun goes down but that’s not always how it works here. They eat when they can afford it.

•••

Leticia Tolano, wife of the pastor for En las Manos de Cristo, left, has come to el Tirabichi to try and get a couple of the waste pickers to come to Sunday church service. Heidi Figueroa, center, has been attending the Evangelical church for two months but decides not to go to this Sunday service. Tolano takes Figueroa's four youngest daughters for church and bible study.

For those who work hard, el Tirabichi can be a gold mine.

Heidi Figueroa arrived in Nogales from Sinaloa as a 15-year-old pregnant dropout. She initially lived with her brother, but that didn’t work out. She worked factory jobs until about three years ago, when she heard there was good money to be made as a waste picker.

Both she and her ex-partner, who lives at the dump, started rummaging to sell material to small recycling companies. The firms stop by daily to buy stacks of cardboard for 5 cents a kilo, or 10 cents for a kilo of plastic bottles, which they then sell to larger factories.

Figueroa, 31, saved enough money to buy scales and now buys from waste pickers herself.

In her heyday, she could make about $200 a week. The minimum wage in Mexico is less than $5 a day.

She runs her own business now, and even though she makes less than half of what she used to, she’s able to feed her seven children. She was recently named one of three leaders to represent the pickers in negotiations with the city.

Figueroa lives in a two-room, wood-and-cinder-block home with a dirt floor that a U.S. church group helped build for her and her children. It’s just a few minutes from the dump on a piece of land she’s paying off.

And she has plans.

“I want to have three bedrooms — one for the girls, one for the boys and one for me; a kitchen; a living room and a bathroom inside,” she says. “I’m not going to be living like this forever.”

Neither are her children.

Luis Figueroa is a quiet, small-framed 12-year-old who wants to be a lawyer when he grows up.

But some days he’d rather be in el Tirabichi than in school.

When he is not helping his mom pick through the waste, he waits for vehicles to pull up and helps unload them for tips.

His mother wants him to be somebody. For that, she says, he has to go to school.

A car arrives in the afternoon and a woman and her daughter call him over. They have new toys and shoes for the children.

Luis grabs a pair of black slip-ons for his little brother, Domingo. If they don’t fit him, maybe his sister Daniela can use them.

He slumps back into the couch under the shade and covers the shoes with a shirt. When another truck comes up the road he jumps, but looks back at the shoes and hesitates. Only when someone promises to watch over them does he run.

When not scavenging, kids play with stray dogs, kick deflated soccer balls, make mud cakes on bottle caps. They don silvery star bracelets, rings and handbags — all salvaged from the dump.

But not all toys are playthings. Inside Figueroa’s home, a toy doctor’s kit, a Barbie and a baby doll — still in their packaging — hang from the wall. They are gifts from U.S. visitors, too precious to play with.

•••

Petra López, 73, followed the city’s dumps for more than five decades until she settled more than 20 years ago at its current location. She had to move, though, after she became ill.

El Tirabichi is coming to an end.

Even Petra López, who’d lived at the dump the longest, left after the March fire.

Doña Petra, 73, scavenged for more than five decades. Wherever the municipal dump moved, she followed and built a room for herself and her family.

It was the only life she had known since arriving from Agua Prieta, sister city to Douglas, as a teenager.

Her seven children — even some of her grandchildren — were raised in these dumps.

“When they were born I would make a bed for them out of a small cardboard box and a neighbor would take care of them while I worked,” she recalls.

But decades of being exposed to methane gases from the rotting garbage made her sick. She was in a coma for eight days, she says, and doctors told her not to go back.

Still, she refused to leave el Tirabichi, her home of 20 years.

Hers was one of the first houses built here. She had several rooms and a courtyard. She was in charge, the one others looked to for guidance.

Now she lives nearby, in a small rental home that a neighborhood evangelical church helped her find. The church is paying for her first two months’ rent.

But she misses the life she left behind.

“There, I was always out, talking with everyone,” she says. “The friendships are what I miss the most.”

It’s 8 p.m. and as Doña Petra sits at home, some of her former neighbors cook dinner while others keep working. A dim streetlight and a nearly full moon make their shadows dance across the mounds of garbage. The clanging of metal fills the air.

In the dump you don’t want to fall asleep. You might miss the next truck.