Tucson’s economy is expected to post healthy gains in jobs, population and income next year, but it’s getting tougher to afford a home here.

Housing affordability is declining as home prices outpace inflation and income growth, University of Arizona economists said Wednesday at an annual forecast breakfast.

Income growth has been slow across the nation, Arizona and Tucson during the recovery from the Great Recession, falling to an annual range of 2 to 3 percent since 2010 from a range of 4 to 5 percent before the recession took hold, said George Hammond, director and research professor at the UA Eller College of Management’s Economic and Business Research Center.

“We continue struggling to generate that wage growth, even with the effects of a higher minimum wage,” Hammond told a crowd of about 300 at the UA forecast breakfast at Loews Ventana Canyon Resort.

Though the accelerating replacement of baby boomers with lower-paid younger workers is depressing wage growth nationwide, UA economists are predicting that personal income in the Tucson metro region will grow 4.1 percent this year and 4.8 percent next year, as labor markets continue to tighten.

But home prices are increasing even faster, rising 7.9 percent over the year in the first quarter alone according to the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Hammond noted. The median home sales price in the Tucson market was $215,000 in April.

The affordability of single-family homes in Tucson slipped in 2017, and lower-income residents — those with annual incomes of less than $35,000 — face a higher housing-cost burden as a percentage of income than Arizona and the nation as a whole.

Even so, Hammond noted that Tucson still leads the U.S. and a group of 10 peer Western cities in an index of home affordability.

“Affordability is still well above levels last seen at the house-price peak” in 2006, Hammond said.

As the Federal Reserve Board continues to raise short-term interest rates, average mortgage interest rates are expected to rise to around 5.4 percent by 2021, from around 4.6 percent now, he said.

JOB GROWTH QUICKENS

The UA economists expect Tucson to add 5,500 jobs this year and 6,000 in 2019, for growth rates of 1.5 percent and 1.6 percent, respectively.

Job growth in Tucson began recovering in 2014 after slipping to near zero during 2012 and 2013 due partly to federal budget cuts.

The projection is about the same as last year when the 5,400 jobs added was the fastest growth rate since 2012.

But that still lagged the Phoenix metro area, at 2.8 percent, and the state at 2.4 percent.

Hammond said Tucson, which has a high percentage of government-related jobs, should benefit from an increase in federal spending in the next couple of years but that growth is expected to flatten by 2021.

Strong construction job gains reflect a significant increase in Tucson housing permits last year, according to revised data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Tucson housing permits hit 4,495 last year, the highest level in 10 years, fueled by a surge in multi-family permits, the UA economists found.

REVISITING NAFTA

With the Trump administration looking to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico and Canada, Hammond noted that Mexico is by far Arizona’s biggest trading partner.

Mexico accounted for 36.3 percent of Arizona merchandise exports to foreign nations in 2017, followed by Canada at 9.9 percent and China at just over 5 percent.

“It’s a very important part of our overall economy and it’s a very important part of Tucson’s economy,” he said.

A rise in the value of the dollar since mid-2014 has made U.S. goods more expensive, contributing to a 17 percent decline in merchandise exports to Mexico in 2016 and 2017, including a drop of 8.3 percent last year, he said, adding the stronger dollar has also cut spending by Mexican visitors.

Hammond says he’s seen some encouraging signs that Mexican exports are stabilizing, but the dollar’s value remains elevated.

An economist with the Federal Reserve Bank told the Eller crowed that NAFTA has been a “complete success” as a trade deal, boosting total cross-border trade by some 300 percent since 1993, the year before NAFTA took effect.

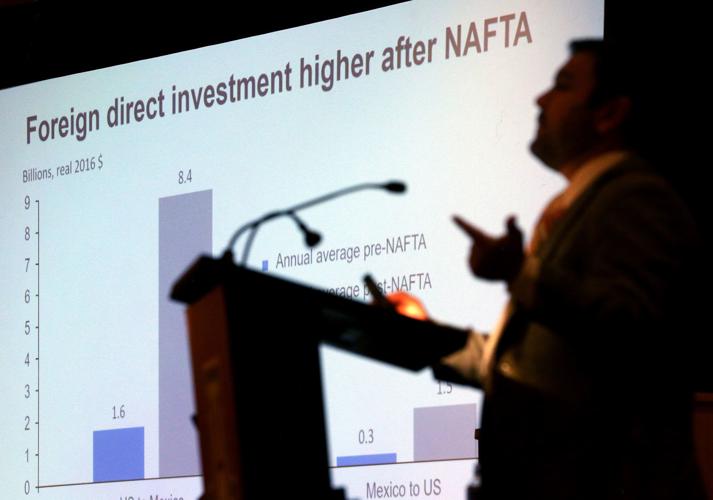

Jesus Cañas, senior business economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, said average tariffs fell most in Mexico as a result of NAFTA, while foreign direct investment by U.S. firms in Mexico and by Mexican companies in the U.S. grew by billions of dollars.

And most of what Mexico exports to the U.S. are “intermediate” goods that feed U.S. manufacturers who in turn export finished products, Cañas said, citing statistics showing those Mexican exports closely track with U.S. export levels.

WINNERS AND LOSERS

But NAFTA created losers, as well as winners, on both sides of the border, Cañas said, noting that his comments reflected his own views and not the Fed’s.

Cañas recalled presidential candidate Ross Perot’s prediction in 1992 that NAFTA would create a “giant sucking sound” of jobs moving to Mexico.

“Those fears were unrealized, but so were the aspirations,” he said.

The free-trade agreement hit manufacturing workers in some areas of the U.S. hard, particularly in communities in the Midwestern Rust Belt where in many cases one factory employed thousands of workers, he said.

NAFTA also boosted wages in Mexico, but those benefits were seen mainly in the industrialized north and did little to relieve high poverty levels in southern Mexico, Cañas said.

“On the aggregate level, we all benefit, but when you concentrate on different regions, you definitely find the losers of free trade,” he said.

Part of the problem, Cañas said, is that economists overestimated the mobility of workers — their ability to move to find higher-wage jobs — as crashing home values, for example, made it uneconomical to sell and leave.

“In some regions, you are not as mobile as we assumed,” he said.

Changes brought on by NAFTA cost Texas some 50,000 jobs, mainly along the border, according to federal statistics cited by Cañas.

But on balance, NAFTA created more jobs than it cost, Cañas said, citing hiring by foreign companies and cross-border maquiladora manufacturing that boosted employment in Texas border cities.

Though the outcome of the current NAFTA negotiations are uncertain, Cañas said NAFTA has given the three signatory countries more leverage to compete with other regions around the globe.

“If we mess with this relationship, who do you think will gain?” he asked. “China, or whomever is our competitor, because we compete as a bloc with the rest of the world.”