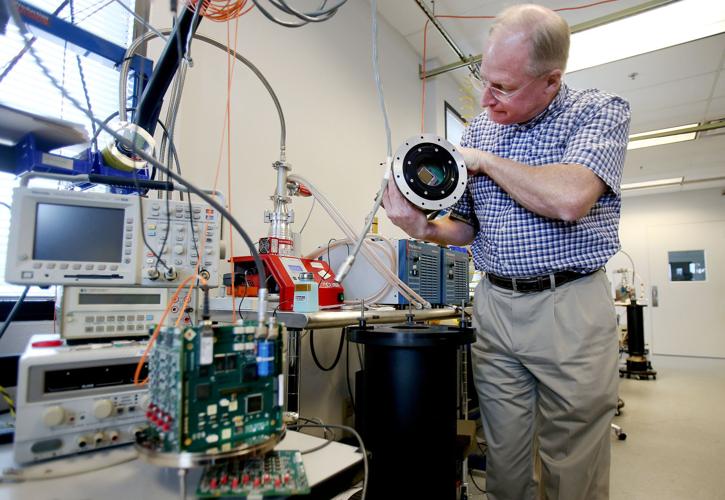

Spectral Instruments Inc. has been building custom scientific cameras for imaging objects as small as a neutron and as large as a galaxy cluster since 1993 in labs west of the Santa Cruz River near downtown Tucson.

“It really spans the whole range of sciences,” said Gary Sims, president of Spectral Instruments. “That’s one of the fun things about this business.”

Sims founded the firm with Keith Copeland. The pair met when Copeland was an undergraduate and Sims was a graduate student at the University of Arizona. They both ended up working at Photometrics, another builder of scientific equipment in Tucson.

Now, their own business takes orders from high-energy physics labs such as Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and institutions with telescopes on mountain peaks around the world, including the contiguous states, Hawaii and Chile.

“There’s not too many mountaintops in the world where there are telescopes where we don’t have a camera,” Sims said.

The University of Arizona though, is an infrequent customer, despite its proximity. Typically, large organizations, such as Steward Observatory, employ their own teams of engineers to create needed technology.

“But then there’s kind of a second tier that doesn’t have the money to have a team of people building their own detectors,” Sims said, which is the market they serve.

Spectral Instruments has about 45 employees, according to Copeland, the firm’s CEO. The number fluctuates depending on the orders received.

When clients order hundreds of cameras to integrate into their own devices, work ramps up to get things done quickly.

Custom cameras, on the other hand, can take a year or two.

PROJECTS UNDERWAY

Spectral Instruments built the new custom cameras for the 0.9-meter Schmidt telescope near Mount Bigelow and the 1.6-meter telescope on Mount Lemmon. The upgrade re-established the Catalina Sky Survey as the world leader in near-Earth asteroid searches.

A camera they’re currently building will be sent to India to map space junk.

Spectral Instruments has also created a sister company, called Spectral Instruments Imaging, which focuses on making the entire apparatus, rather than just the camera.

It is making devices to image fluorescent biomarkers in mice for biological and pharmaceutical research.

The National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California has been using Spectral Instruments’ charge-coupled device — or CCD — cameras for more than 20 years to measure the output of nuclear reactions.

“There they are making a miniature nuclear reaction and using the 192 lasers that fire into this target—which is the size of the head of a pin,” Sims said. “They need instruments to measure the X-rays produced”

But the radiation from these experiments damage the CCDs. “So we’re developing a new generation of CMOS (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) sensors that are more resistant to the radiation,” Sims said.

NEW CAMS IN TOWN

CCDs have a long history in Tucson. The first astronomical image using CCD technology was taken with the 61-inch telescope on Mount Bigelow in 1976 by Jim Janesick, working with Brad Smith, of the UA Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

CCDs are still the most commonly used cameras for science. CMOS technology is newer and used in cellphone cameras.

“(CMOS technology has) been used for a number of years, but what they put in cellphone cameras are really not suitable for making quantitative measurements,” Sims said.

But as CMOS technology develops, it will soon overtake CCDs in terms of standard technology in scientific cameras, he said.

“(CMOS) moves light from one surface to another using an array of optical fibers,” which is then converted into electrical signals, Sims said. “They’re kind of neat things. You go to trade shows and it’s what everyone wants to play with.”

CMOS cameras can get the picture off the detector a thousand times faster than a CCD which allows researchers to get a better snapshot of rapidly moving objects such as molecules, according to Sims.

Now, everything Spectral Instruments is developing is based on CMOS technology, according to Sims and Copeland.

“CMOS is the future,” Copeland said.