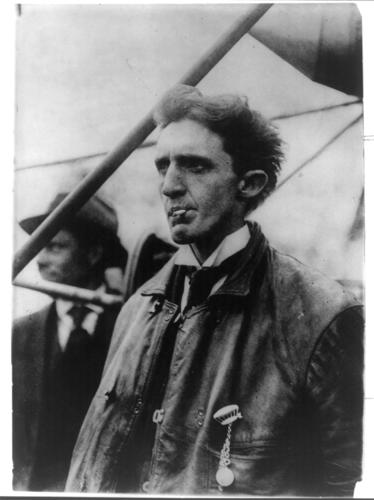

A half-dozen years after the Wright brothers’ first flights in late 1903, the first fearless aviator arrived in the Old Pueblo. Pioneer stunt flyer Charles K. Hamilton thrilled an excited crowd with his machine and airborne stunts, taking off from a makeshift landing field near where the Tucson Convention Center sits today.

“Come to Tucson and See the Man-Bird Fly” promised an advertisement for $1 tickets to the Feb. 19, 1910, Aviation Meet. The event brought the city streets to life thanks to organizers businessmen Mose and Emanuel Drachman and Chamber of Commerce president George F. Kitt, whose family names still hold a place in Tucson. Locals, cowboys, miners and other visitors clustered around Elysian Grove recreation park at the foot of Simpson and Cushing streets.

Each of Hamilton’s ascents ended in calamity. On the first day, a pesky wind current ripped one of the silk wings on his aeroplane (as they were first called). He slammed into the Grove’s newly installed posts for greyhound racing the next day, but he succeeded in flying 3 miles and reaching 700 feet in altitude.

Although Tucson’s event came quickly on the heels of the nation’s first major show in Los Angeles the previous month and Arizona’s first in Phoenix days before, it was a financial disaster since many watched outside the designated area without paying. Over the next two decades, though, Tucson entertained a host of aviators and established a reputation as a pilot friendly city.

As we celebrate Tucson’s 242nd birthday (Aug. 20, 1775) Sunday, William D. Kalt III’s new history of early Arizona aviation, “High in Desert Skies: Early Arizona Aviation,” provides a look at the major developments in an important aspect of our past. He dives deep into the aircraft, personalities and events around the world as aviation took hold. With the focus on Arizona, the book also includes tales of Phoenix and the namesake of Luke Air Force Base, the community of Douglas and Nogales hero Ralph A. O’Neill.

Follow along as Kalt introduces some of these big events and major players.

‘Flying School Girl’ impresses Old Pueblo

After Charles K. Hamilton’s show, it was 1915 before another aerial show came to Tucson. That November, America’s “Flying School Girl,” Katherine Stinson, awed fans at Pima County’s Southern Arizona Fairgrounds. The role of women in early aviation proved significant and, as the Arizona Republican newspaper observed, “It seems to be quite clear that women do not intend to be content with remaining on the earth during the dawn of the great new era of the air.”

Katherine’s brilliant smile, gentle grace and superb flying skills endeared her to Tucsonans during her performance. She shared the fine points of her loop-the-loop trick and carried the city’s first official mail delivery.

Historic airport hosts Army aircraft

The next airplanes to fly into Arizona arrived in December 1918, much to the exhilaration of the town’s aviation boosters. With word that a squadron of Army aircraft would arrive in just three days, city leaders scrambled to locate and clear an airfield. East of present-day Evergreen Cemetery along North Oracle Road, the new landing grounds greeted aviators with great frequency following its groundbreaking.

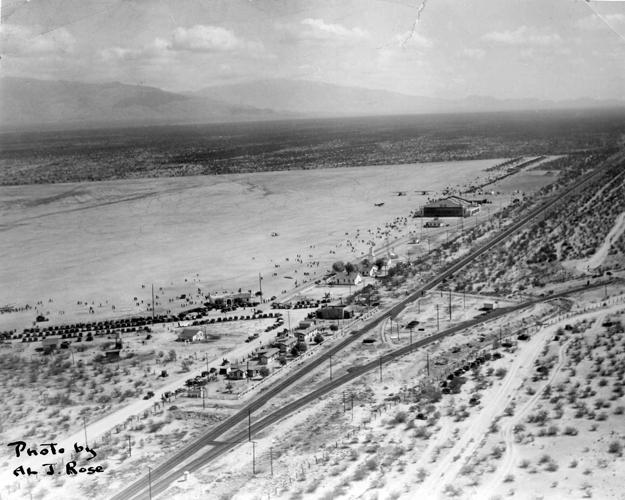

Unsatisfied with the landing strip, however, city leaders pressed for a permanent airport. Mayor Olva C. Parker and Councilman Randolph E. Fishburn led the push and the city established the nation’s first municipally owned airport in the summer of 1919. Located at South Sixth Avenue and Irvington Road, now the Rodeo Grounds, the airfield provided safe haven for incoming airmen and Tucson earned a sterling reputation among flyers.

World Cruisers put Tucson on the map

Hamstrung by the public’s lingering fear of flying, hampered by its remote Southwestern location and blocked by governmental torpidity, Tucson’s airport remained without an airplane hangar when the beacon of national glory shined upon it in 1924.

As the Army’s Douglas World Cruisers returned to the United States on the first around-the-world flight, wear on their engines forced the squadron’s commander, Lowell H. Smith, to alter his flight path and come through Tucson rather than scale the Rocky Mountains on the way to the West Coast. The town of just more than 20,000 relished their visit, which placed it on the map with Paris, Budapest, Strasbourg and others. Kirke T. Moore, dubbed Tucson’s “Daddy of Aviation,” greeted the airmen and six Arizona cities presented them with Navajo blankets at an opulent welcome banquet.

Local visionaries help expand airport

During their 1924 visit the Douglas World Cruiser flyers advised Moore that the city airfield’s runway stood too short for landing their larger planes and the lack of a hangar and mechanical help made the local operation unattractive.

Pima County Engineer John “Mos” Ruthrauff joined Moore and aviation enthusiast Birtsal W. Jones in driving the city’s purchase of 1,280 acres. This airport’s hangar remains today east of Alvernon Way and Golf Links Road and on the edge of Davis-Monthan Air Force base.

How Davis-Monthan received its name

Three of Tucson’s airfields have been designated Davis-Monthan, two municipal fields and today’s Air Force Base. In 1925, the city named the airport at the current Rodeo Grounds in honor of two local pilots who died in airplane crashes: Samuel Howard Davis, a Tucson High School graduate and horseman, and Oscar Monthan (pronounced Mon-tan), a member of a Vail ranching family and one of the Army’s best and foremost engineers.

While little is known of the Davis family to date, Monthan family members remain in the area. Among them is 95-year-old, George R. Monthan, Oscar Monthan’s nephew, who carried on the family’s aerial legacy by piloting fighter planes off aircraft carriers as a career naval aviator.

Lucky Lindy makes glorious landing

With its new airfield already serving airplanes, Tucson marked its early aviation pinnacle when Charles A. Lindbergh arrived in September 1927. Accorded international adulation for the world’s first solo trans-Atlantic flight, he followed his grand achievement with a tour of the United States in the Spirit of St. Louis aircraft.

Six-year-old George Monthan stood with his parents at the local airport on the day America’s flying wonder landed.

“I got to climb around the Spirit of St. Louis,” he recalls. “My dad lifted me up and I looked in the cockpit. Lindbergh was my first real close exposure to flying. When I was old enough, if I saw a group of airplanes landing, I’d jump on my bicycle and race south down Alvernon Way to see them at the airfield.”

Col. Lindbergh’s sole Arizona stop drew an estimated 20,000 spectators to the University of Arizona campus and local florist Hal Burns presented him with the “Spirit of Tucson,” an almost life-size airplane made of cactus. Lindy officially dedicated the new airport Davis-Monthan at the evening’s sumptuous banquet.

After the city moved its municipal airport to its present location in the early 1940s, the military kept and enlarged the airfield, today’s Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. In 1948, the Tucson Airport Authority revived a floundering municipal operation and helped build it into the Tucson International Airport, which now serves more than 3 million passengers annually.

Where to buy the book “High in Desert Skies: Early Arizona Aviation” is available at highindesertskies.com and at the Southern Arizona Transportation Museum, the Arizona Inn Gift Shop. Mount Lemmon’s Living Rainbow Gift Shop, Mostly Books, Antigone Books, the Pima County Public Library, in Mesa at the Commemorative Air Force Museum, and at the Tempe History Museum.