In the book, Charlie finds the ticket in a candy bar called the Whipple Scrumptious Fudgemallow Delight. In the movie, the factory is illustrated in matching style, as a trippy, baroque cartoon: a chocolate river and technicolor lollipop forests.

Candy-making is a dark art, the secret industrial process that imagines and makes the stuff of children’s wildest cravings. In cheery and menacing laboratories, Willy Wonka is preoccupied with research and development, venturing further from the medium of chocolate as he scrapes the burning sky with marshmallow-tipped ice cream wings.

So you might be disappointed, at first, when a real-life chocolate factory tour — at Tucson’s acclaimed Monsoon Chocolate, 234 E. 22nd St. — happens in one big temperature-controlled room.

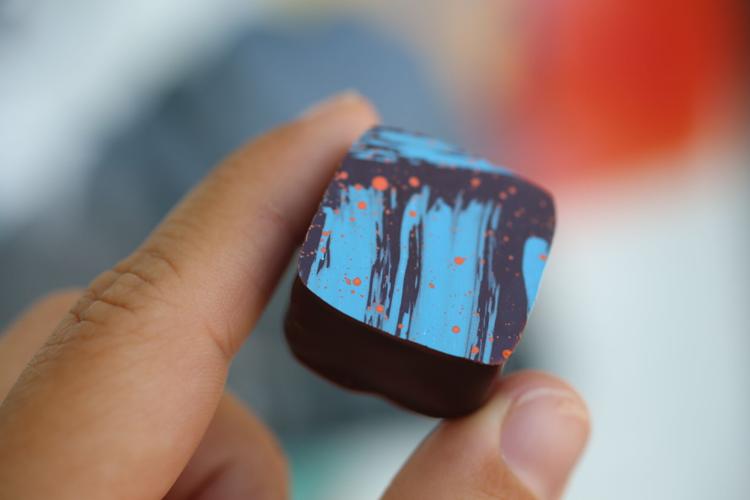

This is a vegan passionfruit lime bonbon from Monsoon Chocolate. Individual bonbons cost $3.97 each.

Indoor windows reveal the depths of the factory: the grinding room or an assembly line of two people. One worker stands in front of a minor chocolate waterfall, arranging squares of ganache into rows. Someone else decorates the confections on the other side. The air smells warmly like the cashew brittle that is cooling on a marble slab around the corner.

The $20 tours, which happen several times throughout May, aren’t ostentatious or whimsical, yet they still seek to inspire. The Monsoon Chocolate factory begins in a room flanked with hefty jute bags, wherein lies the focus of the tour: the beans.

When owner Adam Krantz enters, he bears an iPad instead of a scepter, wonkish circle glasses in place of a satin top hat, hipster tattoos under rolled-up sleeves. Yet one aspect mirrors old Willy Wonka: a gleam in his eye, flirting with fanatical love of chocolate.

Adam commands the tour, yet his showmanship is more as a supporting role: he aims to highlight the wonder of the chocolate itself. The iPad comes out to illustrate the wonders of the plant: elephantine pods that emerge directly from the trunk of the tree, fruits displayed in every color of the rainbow.

Next, a photo of a modest black insect. The chocolate midge, Adam said, is the plant’s only pollinator. “We can hardly see the midge, and they don’t know we exist, but we’re still in this symbiotic relationship,” Adam said. Without its efforts, chocolate wouldn’t exist.

Learn about chocolate making from the bean to bar at the Monsoon Chocolate factory tour.

The material of the tour includes a few precious substances. The first is cacao water, made from the pressed fruit (usually wasted) that surrounds each seed that turns into a cocoa bean. Adam describes the taste of the water as “all my favorite tropical fruits in one,” but this is the first time he’ll talk about how many volatile flavor compounds exist in chocolate.

“This is one of the most complex flavor substances on the planet,” Adam said. “I mean, they’re saying, like, over 1,000 compounds in fermented cacao. It’s wild. You know, things like beer and wine and coffee — they’re all complex flavor foods, but you’re more in the 400 to 600 volatile compounds on those.”

To me, the cacao water tasted like fat-washed orange juice, but other guests identified kiwi. Adam declares, diplomatically, that there isn’t one answer to what it tastes like: we’re all interpreting this staggeringly complex fruit. This is the first time that I see this tour not just as a demonstration of how the sausage is made, but Adam as a broker of these unique and hard-to-find foods that we come here to taste with his guidance.

At Monsoon Chocolate, you're greeted by a case full of bonbon jewels, priced at $3.97 each with lower rates as you purchase in larger quantities.

Most of the chocolate bars that Monsoon sells are single-origin, which means the beans come from a particular farm, growing a particular varietal of cacao, in a tropical country thousands of miles away from Tucson. These farms are small — though chocolate is produced on an industrial level (Adam calls it “Big Chocolate”), the farms that grow the fruit are typically around one acre in size.

“When we say our chocolates are a partnership with farms, we really mean that,” Adam said. The first crucial steps to making chocolate are done on-site: growing and harvesting the fruits, fermenting the beans and then drying them into what we would recognize as a cocoa bean.

Each of these steps require expertise: “You have to know your specific trees, your specific genetics. What looks right in one farm might not be right on the other. And all the pods are ripening at different rates, so you might have just one or two per tree that are ready to harvest.”

Though cacao trees fruit year-round, there are one or two times a year that are peak harvest. Buying the beans can be one of the hardest parts of the business, Adam said. “We’re usually purchasing when [the beans are] ready, when it’s available, and it might not line up with when you’re ready.”

From the farms, the beans get shipped to a warehouse in San Francisco that holds most of the western U.S. supply of cocoa. Then they arrive at Monsoon, where the factory work truly begins.

Adam gets up from the head of the table and takes us into an alcove next to a window into a room with heavy machinery. Two miniature grinding machines are busy at work churning cocoa beans into chocolate.

This grinder turns cocoa beans into particles smaller than 20 microns, a liquid called chocolate liquor.

The machines sit on top of enormous Tupperwares filled with sheathed cocoa beans. Big Chocolate, Adam said, has machines the size of this room that sort out twigs and defective beans from the supply, and even more machinery to winnow the shell from the bean. At Monsoon, these things are done with manual labor and some ingenuity: workers sort the beans by hand, and their winnowing machine is a juicer attached to an industrial vacuum, designed by an engineer friend of Adam’s.

These beans are evaluated based on their size and acidity, and then roasted and aged for maximum flavor and minimal bitterness. Then, they go in the grinder.

The grinder almost seems like a misnomer — if you’re thinking about a coffee grinder, you’re not realizing how small chocolate is ground in order for a smooth finish. These grinders get the coffee beans down to less than 20 microns in size, which essentially turns the beans into a liquid.

This is the second time the tour feels more like a guided tasting: Adam dips sample spoons into each grinder: one contains beans alone, the other has cocoa butter and sugar added. We try them both.

Most of what chocolatiers taste is the chocolate liquor, also called unrefined chocolate. Though the bitterness is sharper in this form, the notes of the chocolate are much easier to identify.

These notes are what make each bar a collaboration between the farmer: they’re the expression of the fruit, soil, latitude, and specialized practices of a farm taking up one acre of land in this world.

When you taste a sample of the finished chocolate bar at the table, the chocolate liquor has shocked your taste buds into being able to recognize the complex flavors hiding underneath the sugar and bitterness we most easily recognize as dark chocolate. Suddenly, your palate feels expansive.

Adam shows us how he smells and snaps the chocolate, to understand its aromatic and textural composition. The snap shows how much of each core ingredient — cocoa, sugar, cocoa butter — is present.

Adam doesn’t tell you what you should be tasting — there are 1,000 directions those volatile flavor compounds can take you.

The last thing you’ll taste on the tour is their lowest cocoa percentage chocolate, a 40% milk chocolate from Ecuadorian beans. Any lower of a cocoa percentage, Adam said, and the nuances of the cocoa will be washed out by sugar and milk. (A big-name candy bar, by the way, probably is clocking in closer to 15 percent, the lowest it can be and still be legally called chocolate by the FDA.)

This vegan masala chai bonbon costs $3.97 and is available for purchase at the Monsoon Chocolate factory.

At the end of the tour, we’re turned loose in their downsized cafe space. The reason these tours can happen, Adam said, is because the factory is moving its local retail operations to a new cafe in the Copenhagen Plaza, 3630 E. Fort Lowell Road.

He tells the family reunion from Washington state that the cafe will be open in a few weeks — pending city approval — and they cheerily indicate that they won’t be in town by that point. Instead, the family will be shipping Monsoon Chocolate to their homes across the country. The Tucson heat can melt the chocolate especially quickly, so this national delivery is no small feat.

“I like to tell people we're a logistics company as much as we're a chocolate company,” Adam said. Shipping, though, saved the company during the pandemic, when they had to close their cafe and stop all tours.

The tour ends with a complimentary goodie: each person gets to pick their own bonbon from their display case. These jewels are hand-decorated (they employ a bon-bon designer to come up with art for each flavor). Their Whiskey Del Bac bonbon recently won the Good Food Award, though it’s one of the least flashy in the case.

After the tour, Adam spirits away to the back of the factory as the tourists mingle in the lobby, buying chocolate and talking about their plans to come.

When I buy a chocolate bar, it’s not to satisfy a craving or as a souvenir of the event. It’s an opportunity to practice what we learned on the tour: to remember when we’re at home, returned to our normal lives, what it means to savor chocolate.

Tours of Monsoon Chocolate's factory are $20 per person. To see available dates and book your ticket, click here. Monsoon Chocolate is located at 234 E. 22nd St., open 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Wednesday-Sunday. Its new cafe is set to open in the coming weeks at 3630 E. Fort Lowell Road.

Great food and drinks start with great water

Restaurants, breweries and coffee shops know that clean, pure water is crucial. You can get that at home too with Kinetico Quality Water. Kinetico removes more contaminants than any other system. Get up to $500 off a non-electric, high efficiency patented Kinetico system (restrictions apply). Visit KineticoTucson.com.

What does "supported by" mean? Click here to learn more.