We want more.

“Guera,” Borderlands Theater’s current offering, gives us tasty pieces of playwright and star Lisandra Tena’s life, full of violence, abandonment, shame and false hopes.

And we want more detail, more insights.

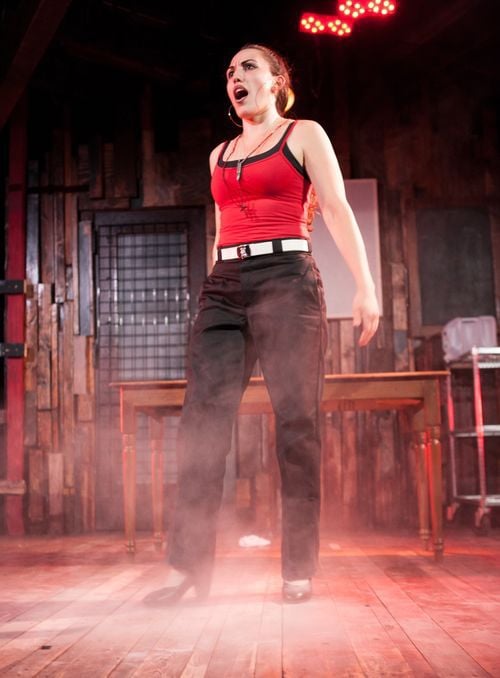

We also want more of Tena, who is a performer full of charm and talent.

“Guera” is the story of her New Mexico childhood. Her mother abandoned her, her brother and her father just after Tena’s birth. Mom was a junkie who would return periodically to promise Tena she’d never miss another birthday, or that she would buy her a beautiful blue dress with shoes to match, or to tell her she loved her only to disappear moments later. Tena’s father married often and the stepmother portrayed in the play was manipulative and cruel. Her father had no problem inflicting physical violence on his daughter.

It’s no wonder she ran away from home when she was 15, living on the streets until she could take it no more. It was then that she found salvation through people who saw her promise and helped her realize it.

Tena quickly seduces the audience with her humor and her sassiness. The conceit is she is a waitress in a restaurant ready to take our order. The program contains a “menu,” and the audience has a choice of one of two dishes for each of the four courses. Each dish calls for a different monologue.

On the Feb. 3 opening night, the audience opted for an appetizer of “El Mexicano.” She quickly and silently slips out of waitress mode and transforms into her father, complete with boots and a Bud. As he sits drinking silently, he notices a small child, scared and longing to be held. He sweeps her up in his arms and dances with her until she calms down. The scene is only the Mexican music and Tena. While we never see the child, we know she is there and understand her fear. And the father won’t let her go until he knows she’s safe. For such a simple, wordless scene, it is shockingly poignant and heartbreaking.

And then the lights come up over the audience and we have the waitress back, ready to take the order for the next course. The audience selects “Ass Kickin’ Posole,” and in it Tena slips a paper flower behind her ear and a sock puppet on her hand. The puppet is her father, the woman the stepmother from hell. What follows is a scene that will make you want to call the Department of Child Safety.

There are two more courses, each darker and more disturbing than the last, and each broken up by Tena’s sassy waitress bantering with the audience.

Bookending each scene with such easy humor is the only way that the riveting stories can be tolerated — relief is essential.

Here’s the thing: If you don’t know some of Tena’s story, this might be difficult to follow. But there is such a beauty and grace to the 90-minute play, you want to stick with it.

And the other thing: We only get snippets of her story. Perhaps Tena will one day broaden it and give us more depth, more insight into what she took from that part of her life, and what it took from her.

Even if she doesn’t, the tasty pieces we got are enough to show us that when Tena is on stage, the audience feasts.