It’s too bad, somehow, that the Writer in Residence at the Pima County Public Library doesn’t actually live in the library.

Authors live in a world of words. Why not sleep in one, too?

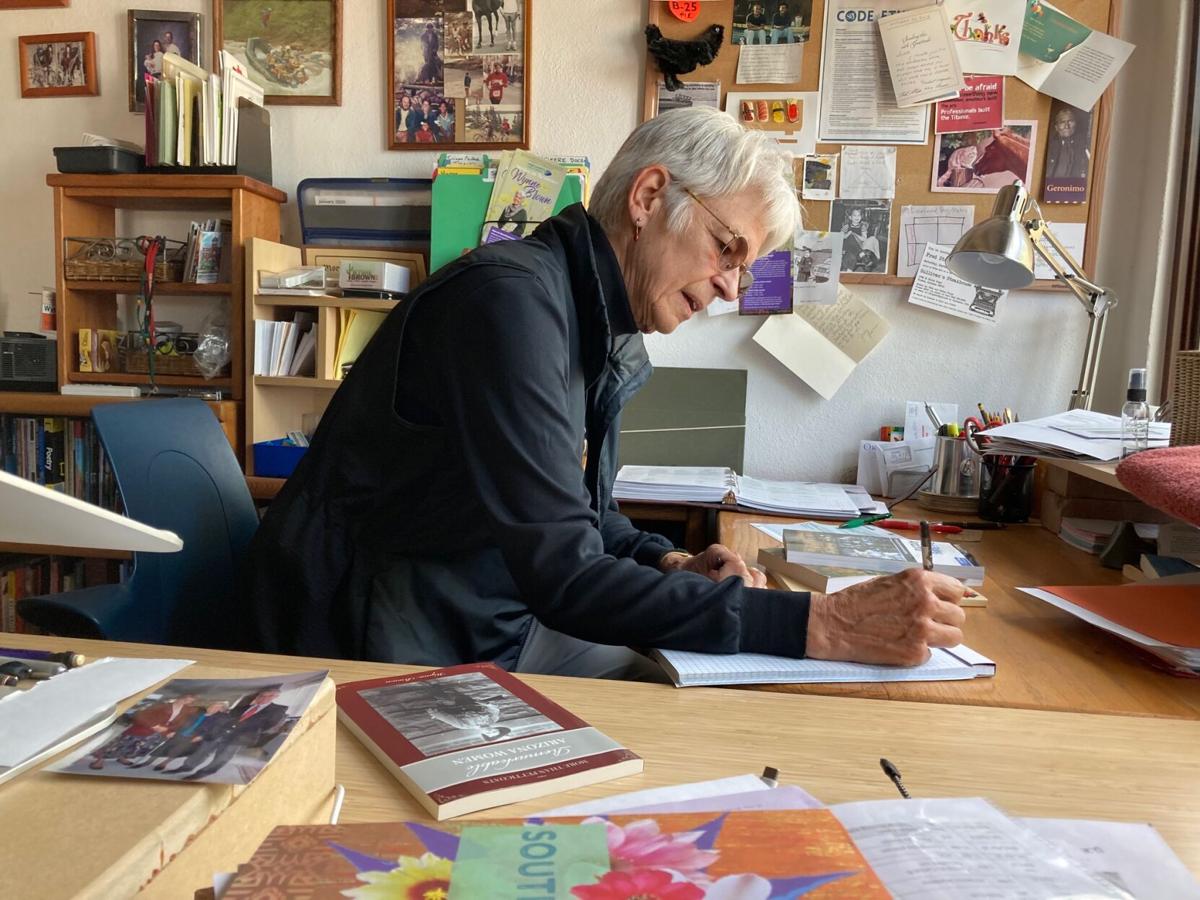

Exhibit A is the library’s current Writer in Residence, Wynne Brown. She has written five books, with a sixth on its way next year. Her illustrations have appeared in dozens more, and her “day job” is to help aspiring authors find the best way to present the stories they have to tell.

“Somebody told me I’m like their literary bartender, someone who’s always there if you need to talk,” Brown said.

Normally, she doesn’t get called until a writer has completed a draft or two. Brown helps them with the next steps. In her role with the library, she helps writers with the first steps.

“I’m meeting people earlier in the process,” Brown explained. “I’m helping them get from Point A to Point B or C, and it’s different every time. This has been one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done. It’s been an honor to be trusted by all these interesting, talented people.”

The Writer in Residence program is a free public service funded by the Arizona State Library and offered through the Pima County Public Library. The libraries make locally based authors available to share their expertise with residents who have stories to tell but aren’t sure how best to tell them.

Brown is the 11th Writer in Residence in Tucson. For the last three months, she has been holding eight one-on-one sessions a week with local writers.

“I’ve probably talked with 60 people about the books they want to write, and it’s been fascinating,” Brown said. “I’ve met people with thrillers, poetry, kids books, nonfiction; one of them is curating a collection of her mother’s poems. ‘We have 30 minutes. How can I help you?’”

Many of Brown’s new mentees will need an editor. She refers them to the list posted by the Editorial Freelancers Association. She referred one writer directly to an agent.

“The woman hasn’t even started writing yet, but she has a great premise,” Brown said. “She needs to get it out there.”

Interestingly, a younger Wynne Brown did not consider herself a writer at all. At Skidmore College, she majored in art and minored in biology. She first came to Tucson to pursue a master’s degree in scientific illustration from a new unit called the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Arizona.

“It was perfect for me,” Brown said. “I’m a naturalist who loves the outdoors. I had a passion for illustrations. I was getting paid to squash plants and draw them!”

Later, she became a copy editor and reporter for the Knoxville News Sentinel. Later still, she found herself writing a book called “More Than Petticoats: Amazing Arizona Women,” which was released in 2003.

“It didn’t go so well,” she recalled. “If you looked for it on Amazon back then, the search tab took you to women’s underwear.”

Still, the word “author” was now on her résumé, and her experience as a naturalist came in handy.

At some point between “Trail Riding Arizona” and the second edition of “Petticoats,” her research introduced her to Sara Plummer Lemmon — a brilliant, relentlessly ambitious botanist best-known for her discoveries in California. It was Lemmon who wrote the bill making the golden poppy California’s state flower.

Just as significantly, at least to us in Tucson, is the fact Sara Lemmon’s name is on our most notable natural landmark: the 9,000-foot mountain just north of town.

If we might cut to the chase here, Brown’s interest in Lemmon led to the recently published “The Forgotten Botanist: Sara Plummer Lemmon’s Life of Science and Art” by Wynne Brown.

It received a Spur Award in biography from the Western Writers of America. It was named one of 2022’s Southwest Books of the Year by the Pima County Public Library.

In many ways, Brown’s name could easily substitute for Lemmon’s in the subtitle. The author’s life and her love of science and art can be found on every page.

“Twelve years ago, I learned that Sara’s papers were housed at UC Berkeley,” Brown said. “I knew they had six linear feet of material. I had no idea what I’d find when I went there, but there were 1,200 pages of handwritten letters. They had 276 of her drawings. I was hooked. One year I shot pictures of half of them on my phone. The next year I shot the rest.”

The archived materials, particularly the correspondence, revealed personal details a biographer can only dream about. Hundreds of those insights can be found in “The Forgotten Botanist.”

Tucson takes up only a small part of the book — Lemmon spent only eight months of her life here — but the experience revealed the dynamo that was Sara Lemmon.

Having failed in their attempt to reach the summit from the south, Sara and John Plummer mounted another assault — this time with rancher Emmerson Oliver Stratton — up the mountain’s north slope. This time they made it, and it was agreed the honor of “first to the top” should go to Sara.

It did, and now we know why.

Footnotes

Brown’s term as the library’s Writer in Residence will end next week. She will pass the literary baton to Lori Alexander, the popular author of books for children and young adults. Alexander, who lives in Oro Valley, will be the Writer in Residence beginning next month.

To make an appointment with Alexander or learn more about the Writer in Residence program, visit library.pima.gov/writer.

The Pima Library Foundation’s next “Virtual Salon” is scheduled for Thursday at 4 p.m. Edison Eskeets and Jim Kristofic will discuss their book, “Send a Runner: A Navajo Honors the Long Walk.” The online program is free and open to everyone. To register, visit thepimalibraryfoundation.org/salons.

The notion of living in a library was explored by author Fiona Davis two years ago. In her historical novel “The Lions of Fifth Avenue,” Davis recounted a time when the Superintendent of the New York Public Library did have an apartment within the library. Not a small one, either. His family lived there, too.