Has your neighbor been acting suspiciously of late? Does the dim light of a laptop glow late into the night? Is the UPS truck now making regular stops in front of his house? Does he appear lost in thought when you wave your morning greeting across the street?

Your neighbor could be planning a bank job, but it is far more likely he’s writing about one.

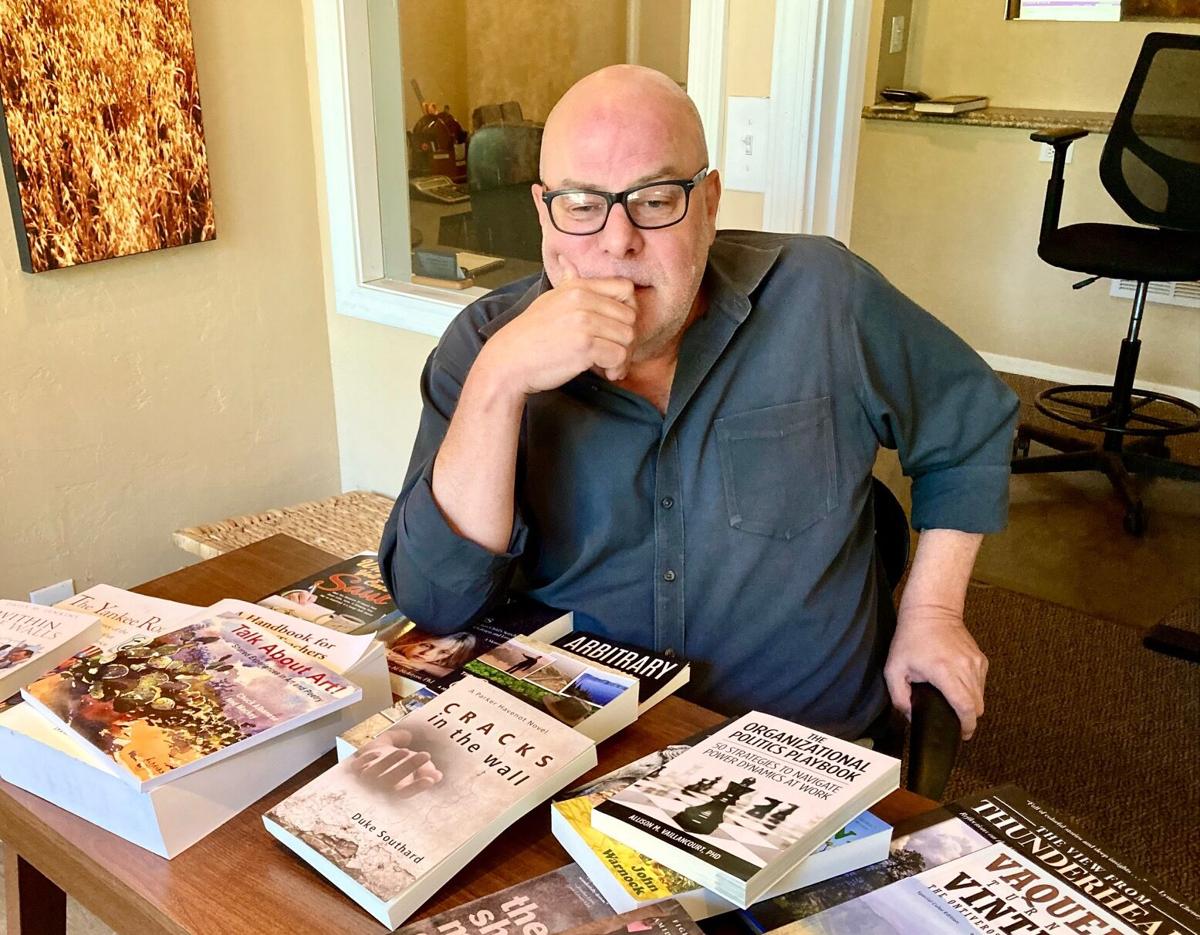

The number of self-published books in the U.S. has exploded in the last five years, and Tucson is no exception.

“It’s hard to put a number on it, but it’s safe to say there are more people writing books — and thinking about writing a book — than ever before,” said Sam Henrie, founder of Wheatmark Publishing. “A huge number of people are writing now.”

He should know.

Wheatmark was Arizona’s first provider of services dedicated to self-publishing authors. Established in 2000, it still is one of the largest in the Western United States. The firm recently distributed 600 royalty checks to Wheatmark-published authors.

All production costs were paid by the authors, making them “self-” or “independently” published books.

“We’re something of a one-stop shop for people who want to publish a book but need help getting it done,” Henrie said.

The process begins with an assessment of each project. How does the author envision the end result? Would the manuscript benefit from additional editing? Do you need someone to design the cover and illustrate the text? How do you see your book being distributed?

Clients can select services a la carte or request them all from Wheatmark.

Henrie got the book bug when he was young, from his parents. His mother wrote a successful self-help book that was published by Penguin. His dad wrote novels but struggled to get them published.

Sam began his own career in technology, specializing in computer networking. While stationed in Amsterdam in the mid-1990s, he learned about “print-on-demand” and online bookstores.

“I realized my dad could now publish his own book without needing a second mortgage,” Henrie said, and his vision soon became Wheatmark.

Tucson has long been a hotbed of literature. Barbara Kingsolver and J.A. Jance grew up in the area. Larry McMurtry and Father Andrew Greeley wintered here. In 1990, there were more than 50 independent bookstores in a city of 400,000 people.

Henrie suspects a number of Tucson’s readers were closet writers, too.

“In those days,” he recalled, “you sent your manuscript to 40 different publishers and agents and hoped one of them would like it. Who knows how many people were writing books that we never heard about.”

If anything, the odds of a newcomer being published by a Big 5 publisher now are longer than ever, Henrie said.

“Unless you know someone, your odds are pretty much zero, but almost anyone can publish their own book,” he said.

Wheatmark alone has 60 books in process, and Henrie suspects there are hundreds — perhaps thousands — of partially developed books living in laptops across Pima County.

These projects range from autobiographies written for the author’s grandchildren to serious works of literary fiction.

Every now and then, a self-published author hits the jackpot. Lisa Genova self-published “Still Alice” in 2007. It later became a bestseller published in 20 languages and an Academy Award-winning movie for actress Julianne Moore.

Far more common are the books that wind up in boxes stacked in the author’s garage. According to Tonerbuzz.com, the average self-published book sells about 200 copies.

“I don’t think anyone writes a book thinking it will become a bestseller,” Henrie said. “Nobody goes into this thinking it will make them rich. People self-publish books for the same reason they use Twitter or tell stories. If you think you have something to say, you want to say it.”

Henrie said Wheatmark’s clients tend to be older, well-educated, middle class and up.

Tucson’s popularity among retirees, and its longtime appeal to academics, make it fertile ground for prospective authors.

If you would like to become one of them, it’s easy to begin the journey. Just turn out the lights, open your laptop, and keep an eye out for UPS deliveries to your front door.

Footnotes

Good news from The Book Stop, Tucson’s oldest bookstore: There is no news. The venerable shop on North Fourth Avenue is still open five days a week despite the passing of co-owner Tina Bailey last June.

“We’re just taking things one week at a time, and we’ll see what happens,” said Bailey’s business partner, Claire Fellows. Bailey and Fellows purchased the store in 1992. Fellows now shares the keys with Bailey’s sister, Anne Lane. The Book Stop is open 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays and noon-5 p.m. Sundays.

The Martha Cooper Branch Library in Midtown will close for at least a year beginning June 27. A major renovation and construction project will double the library’s size and create a large indoor-outdoor meeting and event space. Located on Catalina Avenue near Catalina High School, the library hopes to reopen in the summer of 2023.

The Pima County Public Library has expanded hours at a number of its branch locations. Several are now open Saturday. To check the branch nearest you, visit the library website: pima.bibliocommons.com/locations

About 1 million new titles were published in the United States last year. Half of them were independently published.

Book sales are surging throughout the United States, but studies show it is because readers are reading more. Twenty-seven percent of U.S. adults did not read a single book last year. Fourteen percent do not know how to read at all.