A flock of chicken-centric art is roosting at the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun in the Foothills.

The chickens created by impressionist artist Ettore “Ted” DeGrazia (1909-1982) are strutting, scratching, fighting, and being mourned, chased, carried to market and toted like a fashion accessory.

The chickens show the depth and variety of DeGrazia’s styles: Some of the birds burst with exuberance and joy through bold brushstrokes and bright colors, others are palette-knife thick, dark and brooding, while others are simple and crisp.

The 42-piece exhibit of oil and watercolor paintings, sketches, screen prints, and metal and ceramic sculptures was plucked from the more than 14,000-plus piece archive of the DeGrazia Foundation, which maintains and operates the collection, gallery and related activities, says Jim Jenkins, collections manager/curator.

“Chickens are trending in Tucson,” Jenkins says, noting the number of coops popping up in area backyards. Couple that interest with the hundreds of chickens that DeGrazia painted and shaped, and Jenkins saw a theme to showcase the depth and reach of the artist’s style and technique.

The exhibit, which includes several pieces never shown before, has some atypical pieces, such as a small piece that appears to be a sketch of a metal sculpture and a design for textiles with handwritten notes.

Detail of the undated watercolor “Chicken Crates,” which may have originally been a design for a fabric.

MARKETING AND MAKING ART

DeGrazia’s commercial success brought fame and critical disdain.

Mention the name DeGrazia and images of dancing, doe-eyed American Indian children often come to mind. That style and subject matter became iconic after his “Los Ninos” image used for the 1960 UNICEF Christmas card sold millions and pushed DeGrazia toward the dubious title as “the most reproduced artist in the world.”

However, the bright colors, gentle, graceful nature of the children and other figures in his works caused some critics to dismiss him as kitschy.

Arizona Highways magazine began publishing DeGrazia images and features about the artist in 1941, which also helped propel his popularity. Jenkins says he hopes to curate a future show of images used on the magazine’s cover and interior pages.

Jenkins says DeGrazia did not use models, but painted and rendered the images from his mind.

DeGrazia, whose parents immigrated from Italy, was born in the copper-mining town of Morenci. The family returned to Italy from 1920 to 1925. The years spent in Italy are evident in some of DeGrazia’s pieces, such as those that recall European circus clowns with cone-shaped hats. The paintings of chickens being taken to market in the current show may have also been influenced by his time in Europe.

Italy detoured his American education — he forgot his English and was forced to start over in first grade at age 16. He eventually graduated from Morenci High School when he was 23.

“Chicken Fight,” an undated watercolor, was selected for the exhibit because of its exuberant brushwork.

An accomplished trumpet player, DeGrazia led a band that performed popular music and compositions DeGrazia wrote in the 1930s — you can hear his arrangements at the gallery. He also worked as a landscaper, miner and managed a theater in Bisbee.

On vacation to Mexico City in 1942, DeGrazia met muralist Diego Rivera and became his apprentice. DeGrazia’s social realism-influenced pieces include “A Prayer for the Poor” in the current show.

He received bachelor’s degrees in art education and fine arts, and completed a master’s degree in art education in 1945, with a 60-page thesis “Art and Its Relation to Music In Music Education.”

When he graduated on the cusp of the end of World War II, he found little interest in his work. No one wanted to represent him, so he decided to represent himself, Jenkins says. DeGrazia set up a gallery on the southeast corner of Prince Road and Campbell Avenue.

Untitled watercolor of a boy with a rooster, a piece from the early 1950s, is an iconic work.

DeGrazia was an artist, and businessman, and master at promotion, says Jenkins. He sat in the gallery every day talking and greeting guests, working at night.

He was a bit like Mark Twain, says Jenkins, and he told tall tales. Dressed like a prospector — he did pan for gold in the Superstition Mountains — he told stories of womanizing, multiple wives and drinking that ballooned his image and reputation.

His paintings, prints and the licensing of his art for greeting cards and bric-a-brac raked in millions.

DeGrazia made headlines when he protested the Federal Inheritance Tax by burning about 100 of his paintings worth about $1.5 million in 1976.

GALLERY IN THE SUN

DeGrazia and his second wife, Marion Sheret, a sculptor from New York, felt the crunch of city expansion at the Prince and Campbell location and purchased 10 out-of-the-way acres at the foot of the Santa Catalina Mountains.

DeGrazia, with the help of his friends, built a mission on the site using adobe bricks made on-site with water hauled up from a nearby wash. DeGrazia’s home and a small gallery followed.

The iron gates to the gallery — a replica of the Yuma Territorial Prison gate — swung open in 1965. The original home of the artist and his wife Marion, the mission (currently closed because of a fire), the expanded gallery and the cactus corral sit in what is now a National Historic District.

The exhibit includes several pieces never shown before. This is the expressionistic portrait “Pink Rooster,” oil, 1948.

Jenkins says DeGrazia continued to spend every day from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. hanging out in the lobby of one of the two galleries, chatting with guests and promoting his work, which was done after midnight.

“DeGrazia’s Chickens” lines two rooms of the gallery, which is packed with architectural art: Bas-relief panels by his wife, flooring made of pieces of cholla cactus, a hallway designed to elongate the visual shape of the rooms.

There are six dedicated rooms in the gallery housing permanent collections on Southwestern subjects: Padre Kino, Cabeza de Vaca, Papago Indian legends, a retrospective collection, the Yaqui Easter and the bullfight. Some of the paintings are hung with string, as DeGrazia had.

Jenkins estimates that fewer than 5 percent of the foundation’s DeGrazia originals — oils, watercolors, sketches, serigraphs, lithographs, sculptures, ceramics and jewelry — are on display.

None of the foundation’s pieces are for sale, but there is a consignment room in the gallery where private collectors sell originals.

“Red Chicken Yellow Chicken,” oil, 1948, is “all about the chickens,” says exhibit curator Jim Jenkins.

“A Prayer for the Poor,” oil, 1952, uses chickens as symbolic shorthand for poverty. The “DeGrazia’s Chickens” exhibit features 42 artworks, including oil and watercolor paintings, sketches, screen prints, and metal and ceramic sculptures.

Photos: Ted DeGrazia and the Gallery in the Sun

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

In this July, 1964 photo, artist Ted DeGrazia, who learned his mural techniques from the Mexican masters Diego Rivera and Jose Orozco, looks at his first mural in mosaic, a 96-square-foot scene depicting medicine men healing the sick. It was commissioned by Sherwood Medical Terrace office building at 8230 E. Broadway Road.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

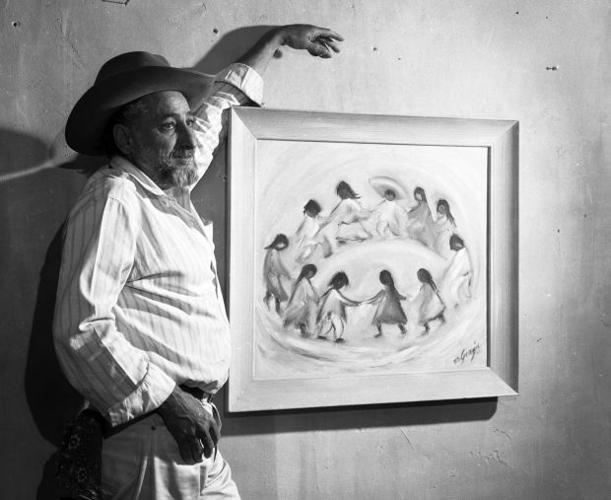

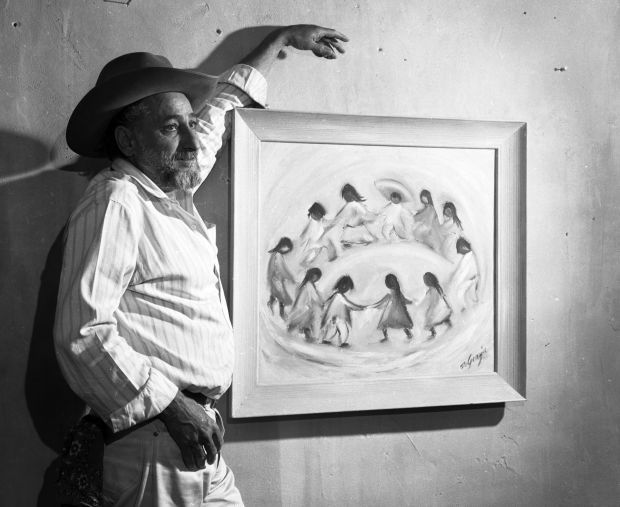

Tucson artist Ted DeGrazia in April, 1960, next to "Los Niños," which was chosen as the official Christmas card by UNICEF in 1960.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted DeGrazia in Italy when he was about 12 years old.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted DeGrazia, left, and other family members taken around 1924 in Italy.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted DeGrazia circa 1935

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted DeGrazia, far right, leads his band in the early 1930s. Money earned from the band's gigs helped pay DeGrazia's way through the University of Arizona.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted DeGrazia, and wife, Marion, in the late 1940s outside his studio at North Campbell Avenue and East Prince Road.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

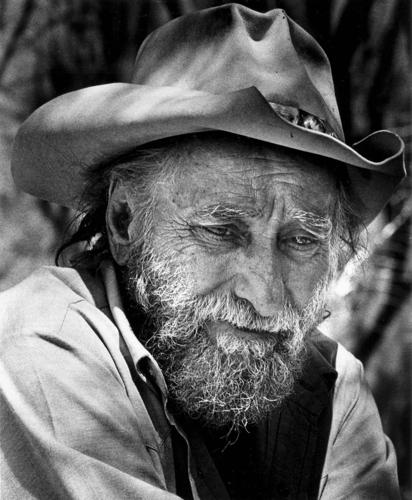

Undated photo of Tucson artist Ted DeGrazia

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

In the early 1950s, Ted DeGrazia began building his Mission in the Sun, part of what is now his Gallery in the Sun on North Swan Road.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

In 1952, Ted DeGrazia built the Mission in the Sun as the first building constructed on the property in memory of Padre Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit priest, and dedicated the mission to Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Children emerge from DeGrazia Mission in the Sun north of Tucson during Las Posadas procession in the 1960s.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted and Marion hugging: Ted and Marion DeGrazia outside his Gallery in the Sun, sometime in the early 1970s.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted with cigarette: Ted DeGrazia liked to promote a somewhat renegade image from time to time, as in this photo taken around 1970.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Tucson artist Ted DeGrazia with Judith Whittington in 1965.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Tucson artist Ted DeGrazia at work in 1962.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Academy Award-winning actor Broderick Crawford with Tucson artist Ted DeGrazia in 1966.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Tucson artist Ted DeGrazia harvesting prickly pear cactus in 1962,

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Artist's studio adjacent to the home of Ted DeGrazia in Tucson, shown in 1964.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Fireplace and with beaded screen in the main room of the Ted DeGrazia home, photographed in 1964.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Guest cottage at Ted DeGrazia's home in Tucson, shown in 1964.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Inlayed concrete floors and textured walls in the DeGrazia's Gallery in the Sun, shown in 1966.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Exterior of DeGrazia's Gallery in the Sun in 1966.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Entrance to DeGrazia's Gallery in the Sun, shown in 1966, was designed to look like a mine shaft with heavy timbers and shored rock walls.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Artist Ted DeGrazia signs the sketch of an angel for six-year-old Dora Jones of Chinle, a patient at the Special Neurology Clinic in Tucson, on Dec. 20, 1969.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Artist Ted DeGrazia, left, an art director on a film about himself, takes direction from Joel Harrison in August, 1966.

Ted DeGrazia / Gallery in the Sun

Updated

Artist Ted DeGrazia at the Gallery in the Sun on Swan Road north of Tucson on Aug. 24, 1966.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

DeGrazia with his 1957 oil painting "Los Niños", which was a best-selling UNICEF card in 1960.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Tucson artist Ted DeGrazia in 1972.

Ted DeGrazia

Updated

Ted DeGrazia, shirtless, looking into the distrance, pensive: Ted DeGrazia, looking somewhat pensive, in the early 1970s.