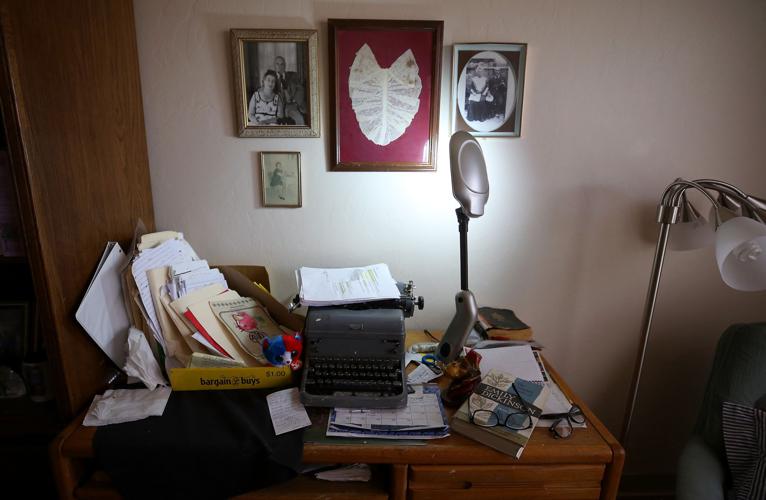

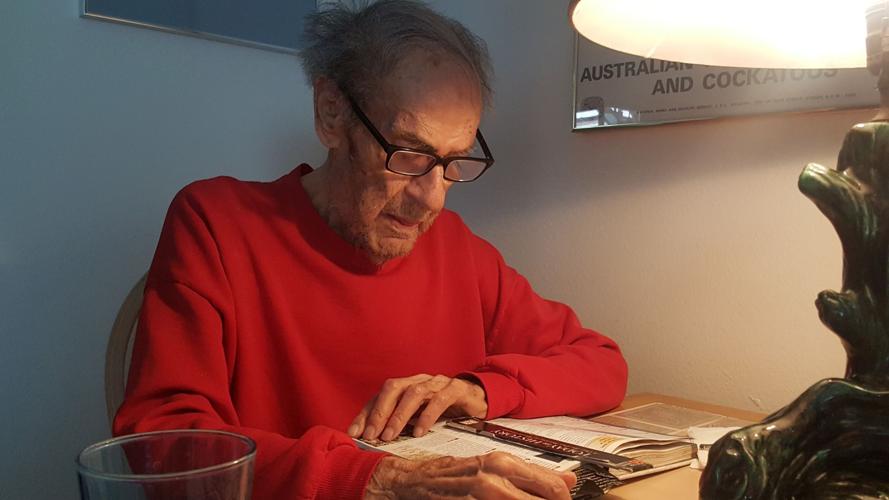

Frederic Balazs sits for hours a day in an armchair next to his small desk, reading poetry anthologies, philosophical writings and thick biographies of world figures from Benjamin Franklin to Mark Twain.

When his eyes and body grow tired of reading, and the single bed on the other side of his small Sierra del Sol room beckons, he sets the books down next to an old Royal typewriter that has been collecting dust since he arrived at the care facility last summer.

Three fat manila folders, heavy from the weight of nearly 500 typewritten pages, lean against the machine, the bulk of the memoirs that Balazs has been pecking out on that typewriter since late 2013.

He got to thinking back then, not long after turning 94, that he had a lot to say. And the clock was ticking; there would come a day when he could no longer tap into those memories of growing up in Budapest, conducting the Tucson Symphony Orchestra, composing dozens of symphony and chamber works, meeting some of the most important musical figures of his day and raising his family of six in the Tucson desert.

Every once in a while, Balazs will look at those files and consider, for a moment, putting a piece of paper in the typewriter and picking up where he left off. But it has been months, maybe even a year, since he last worked on his memoirs. The memories are still sharp — when he tells stories, he weaves in such vivid details you feel like you are reliving the moments with him — but his fingers can’t keep up with his thoughts.

“My whole body aches,” he said recently, his native Hungarian accent still thick after more than 70 years in the United States. “I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t in pain.”

Balazs got sick earlier this year. His runny eyes, long an irritant, started failing him. His hearing deteriorated to the point that simple conversations became frustrating. Then he started losing his balance; he fell a couple of times. One medical mishap after another landed him in the hospital late last spring, then in a temporary care facility before he moved into Sierra del Sol Memory Care last summer.

It took Balazs a couple months to make friends, and even then he only told them bits and pieces of his story.

Here, among the retired veterans, teachers, business executives and artists, Balazs is anonymous.

A milestone day

It was several minutes before he heard the knocks that Tuesday morning.

It was his neighbors Louise and Tom.

“Happy birthday!” they yelled when he answered the door in his bare feet, his thin grey hair mussed as if he had just awakened.

Balazs looked befuddled.

The pair broke out in a chorus of “Happy Birthday” and Balazs, leaning on his walker, smiled, nearly blushing at the attention.

“Ninety-eight,” exclaimed Louise, as Tom stuffed a $1 bill in Balazs’ hand. He looked down at the bill and shoved it into his pocket.

Louise had recently moved in across the hall; she was in her mid-80s and said she wasn’t sure she could imagine herself reaching 98. Tom said he was in his early 70s and didn’t really have any thoughts about age on that morning; he was wearing a bike helmet and said he was going on a ride, maybe hit two, three miles before he was finished.

A nurse’s aide followed Balazs into his room as Louise and Tom went on their way.

“It’s your birthday? Happy birthday,” she told him as she portioned out his daily regiment of pills and eye drops.

Balazs sat gingerly on the seat of his walker and with trembling hands took each pill individually.

A visitor in the room asked the woman if she knew Balazs’ story: No, she answered.

For the longest time after he arrived at Sierra del Sol, no one knew Frederic Balazs’ accomplishments — that as the TSO gets ready to celebrate its 90th anniversary in the 2018-19 season, Balazs had been the person largely responsible for laying the groundwork for the artistic excellence in today’s orchestra.

In fact, few people outside his small and shrinking circle of friends and family know. The last time the spotlight shined on Balazs’ Tucson history was in 2009, on the eve of his 90th birthday. The symphony performed premieres of two of his compositions in his honor.

“He’s forgotten. His generation has passed,” said Stephen Balazs, the oldest of Balazs’ six children. “There are very few of the old network of friends left.”

Balazs in recent months has started to share some of his stories about conducting at the TSO and around the world, name-dropping to his new friends some of the music celebrities — among them big band leader Benny Goodman, contralto Marian Anderson, conductor Leopold Stokowski, and composers Aaron Copland, Ferde Grofé and Tucson-born Ulysses Kay — whom he hosted in his 15 seasons with the TSO, from 1952 to 1966.

Those stories fill the pages of his memoirs.

But very few people have read them.

The bells tolled

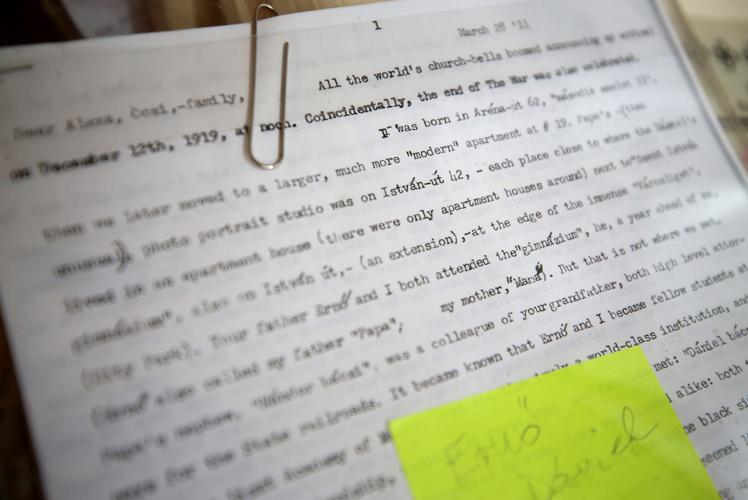

“It was twelve o’clock on the twelfth of December in the year of nineteen-nineteen when all the church bells began to toll, boom, clang, boing and kept on toiling, clanging and boinging in an overlapping drone over our great beautiful city of Budapest, not only in Budapest but the world over (a tradition that continues to this day) in celebration of my arrival into this new world of mine. It is a coincidence that it was also a signal of thanksgiving celebrating the end of World War I, ‘the last of all war.’”

It was the beginning of Balazs’ story and just one of many scenes of his life that he wrote about, moments he didn’t want to get lost in the labyrinth of age.

He recounts memories of his childhood in his native Budapest with his father, a portrait photographer, who got him his first violin and insisted he play “Papa’s favorite, Hubay’s ‘Hejre Kati’ (Get Hep Katy or something like that), that is a piece of Hungarian tunes in a virtuoso version which I disliked with a passion,” he wrote. Each time he played it, “Papa raised his right hand smiling and delighted, his index finger pointing skyward, dangling it along with the rhythm, his eyes shining in pride of me. I was cursed playing that wretched piece for the rest of my musical life.”

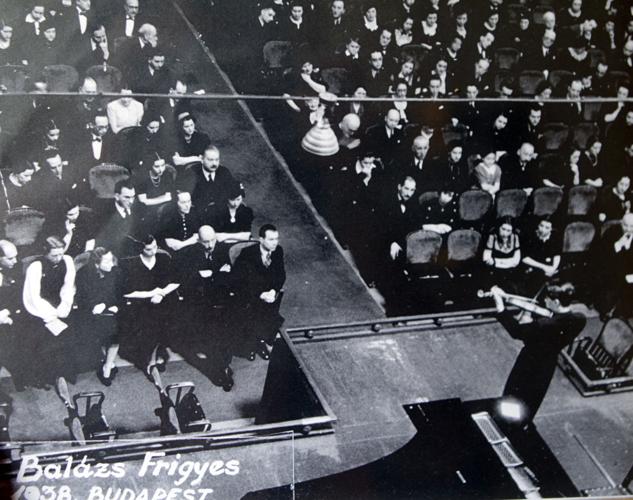

He recalls studying at the Royal Academy of Music under Hungarian composers Béla Bartók, Ernst von Dohnányi and Eugen Huber. When he was 17, he landed the concertmaster position with the Budapest Symphony Orchestra, one of the youngest players to serve in that position with one of Europe’s finest orchestras of the day.

It was his violin prowess that allowed him to escape Hungary in 1939 as the country was being squeezed by the communists from Russia and the Nazis from Germany. Balazs had won a prestigious violin competition and was granted a visa to go to the United States “to represent the cultural achievements of the Hungarian nation,” he said. His brother and sister-in-law were already in the U.S.

“For a man who was ambitious and artistic, that was no place to be for sure,” Balazs said back in May, sitting at the table in his foothills condo, weeks before his health took its bad turn.

Although his recent health issues have left him weak of body, his mind is still sharp, and when you get him to talking he will tell you detailed stories going back 50, 60 years. He recounts the boat trip from France to New York City in choppy waters that sometimes jerked and rattled the boat. When he landed in New York, he jumped into a musical life of performing, conducting and composing before joining the Army just after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He served four years before moving to Texas to become music director of the Wichita Falls Symphony, a couple hours drive from his sister, who was living among fellow Hungarians that included her childhood friend Zsa Zsa Gabor. Along the way, he brushed up against greatness, performing under legendary conductors including Bruno Walter, Arturo Toscanini and Wilhelm Furtwängler.

“He is such a good storyteller. He has a great sense of humor,” said Ann Iveson, who was the principal cellist in Balazs’ TSO. She played in the orchestra from 1959 through the mid-1990s.

Glimpses of his life in Tucson course throughout his memoirs, stories of raising his six kids with his wife, Ann, an accomplished pianist from Texas. The couple met during his Wichita Falls days, and although she gave up her career to support his, they performed as a duet in recitals for several years, he recalled. She also was a guest pianist with the TSO.

“I remember as a kid, with the chaos of dogs and kids, he would get in the middle of it and compose,” recalled Stephen Balazs. “Then every now and then he would get up and play a few chords on the piano and then go back to writing. To me that was always amazing.

“I never really realized how unnormal my childhood was,” he added. “I thought it was pretty normal to come home covered in desert dirt and see these tremendous people in our living room. It didn’t make an impression on me at all. In fact, I thought it was pretty boring.”

“He took us to a lot of his rehearsals and that exposed us to the instruments and the music and the people,” recalled daughter Cheryl Balazs Chester, who studied cello as a child and played in her father’s summer orchestra in Madison, Wisconsin. “We are all pretty talented and gifted musically.”

House guests included the who’s who of Tucson musicians when his parents hosted artist receptions, including a big party for Benny Goodman. Chester, who was 5 or 6 at the time, said she remembers sitting on Goodman’s lap.

“We just treated them like just another guy in the house, let’s go play ball,” she recalled.

When Marian Anderson came to the house, it was the first time Chester had seen an African-American woman up close. And there was the day when a soft-spoken Texan “with a carrot-top head” came to see their mother. The two old friends sat at the piano and toyed around with a melody.

“He would say, ‘Ann, how does that sound to you?’ And she would say, ‘Van, try it this way,’” recalled Stephen, a retired California teacher who splits his time between Tucson and Montana. “I didn’t realize it was Van Cliburn.”

In one of his Tucson visits, Cliburn, namesake of the prestigious international piano competition in Texas, performed with Balazs’ TSO.

Transforming an orchestra

The Tucson Symphony Orchestra had 75 applicants for the full-time conductor’s job in 1952. Frederic Balazs stood out largely because of what he had accomplished in Wichita Falls. In four years, he had grown the Texas orchestra from a small community ensemble to 85 members that needed a 3,000-seat auditorium to accommodate its growing popularity. Season ticketholders numbered 2,500 and Balazs had launched community outreach and youth programs. A prolific composer, he also had a growing reputation for programming works by American and new composers.

These were the skills that the TSO believed could transform the orchestra, founded in 1928, into a regional voice.

“Without a conductor of his vision, we would not be where we are today,” said TSO principal harpist Patricia Harris, whom Balazs hired in 1964 when she was an 18-year-old University of Arizona freshman.

When he first arrived, many of the TSO players were not professional musicians. They were college students or public school music teachers. They were paid little if anything for their services and the orchestra performed only a few concerts a season.

“He was doing the best he could with the players he had, a lot of volunteers and people who could play very well, and he made an orchestra from it,” recalled Iveson, who said that Balazs never treated the musicians as less than professional.

“I think he was always proud of what his players did. He felt that he made them grow to their best potential. He made music more than they knew they could produce,” she said.

Iveson said Balazs formed a TSO string quartet — he was one of the violinists — and they would perform around the region.

“He’d play a whole Bach violin suite. And he was not pretentious,” Iveson said. “He liked to mix with the common man. He knew that was something true.”

Harris played with Balazs just two years before he left for a job in Cincinnati. She remembers that he was “fair and did some great music.” His biggest contribution to the TSO was “encouraging longevity and setting us up for success.”

“I think he was instrumental and absolutely supportive of building musicians to the best they could be,” she said.

Coming home

Balazs left Tucson in 1966 for a job in Cincinnati. He went on to conduct in Hawaii and for years in San Luis Obispo, California, where he founded a young musicians program that was featured in an NBC Evening News segment. He guest-conducted all over the world, making lasting friendships along the way, and continued composing.

“When dad visited Montana he would come with his grocery bag of tax receipts and his manuscripts,” Stephen recalled. “He would spread these manuscripts out on the table and start composing music.”

After 40 years, Balazs returned home to Tucson about a decade ago. Iveson and her husband, William, had kept in touch with him over the years, visiting him several times in California and once in Vermont, where he was teaching a summer program. But on one of their last visits she noticed that Balazs was starting to slow down. His eyesight was deteriorating and he didn’t seem as energetic as she had known him to be. She convinced him he should come home, be closer to family. She could even hook him up with a fine doctor, her daughter. Dr. Kathleen Iveson.

For several years after returning to Tucson, Balazs seem to regain some of the skip in the step. He lived by himself, drove his own car, swam 10 to 12 laps a day in his condo community pool and regularly went out to lunch with friends. He also organized a few community concerts with musicians from the Faro Islands whom he had become close with.

But age has a way of robbing us of the simple things we take for granted. Eyesight fails and you can no longer drive. You get sick and suddenly your body starts rebelling in ways you hadn’t imagined.

“I love living alone,” Balazs said last May, sitting at the table and thumbing through a worn copy of the History Channel’s “This Day In History.” “You find yourself. You begin to discover reality. You find the reality right here.”

His reality at that point included relying on a walker donated by Iveson. He dubbed it Winthrop the Walker.

Not long after that conversation in May, Balazs got sick and his life changed dramatically.

“They determined it would be best if he had a level of care that he couldn’t get on his own,” his daughter said. “But he’s still going strong.”

“I cannot go to the Olympics yet, but I’m walking,” Balazs said in August, sitting on an armchair in his Sierra del Sol room, propped up by several pillows. “I feel good here. But sometimes I lose two or three days. I don’t sleep. I go to the bathroom 12 times. I’m not shaking my fist to the heavens like Beethoven. It’s the life you’ve got and I’m not mad.

“I had an incredibly rich life,” he said. “I’m very fortunate.”