Before the novel coronavirus claimed its first known American victim, President Trump was already reaching to connect the disease to the U.S.-Mexico border.

During a Feb. 28 rally in South Carolina, he contended that we needed to build more border wall to keep the virus out, though it was already in and spreading.

“We must understand that border security is also health security,” Trump argued. “We will do everything in our power to keep the infection and those carrying the infection from entering our country.”

That same day, the U.S. had 63 known cases of COVID-19, and Mexico announced its first two confirmed cases. The next day, King County, Washington, announced a death from COVID-19, at the time the first known coronavirus death in North America.

The United States started as the region’s hot spot for the new infection and has only extended its lead. In April, Guatemala’s health minister complained that the United States was deporting infected people to his country and referred to our country as the “Wuhan of the Americas.”

Nevertheless, Trump and some of his allies have continued trying to frame illegal crossings of the Mexican border as a top potential source of coronavirus in the United States.

Also on Feb. 28, nine members of Congress, including Reps. Paul Gosar and Andy Biggs of Arizona, co-signed a letter to the secretaries of Homeland Security, Defense and Health and Human Services, demanding to know what was being done about cross-border spread from illegal crossings.

“Given the porous nature of our border, and the continued lack of operational control due to the influence of dangerous cartels, it is foreseeable, indeed predictable, that any outbreak in Central America or Mexico could cause a rush to our border,” they wrote.

Patients did eventually come from Mexico to U.S. border states, but they weren’t rushing an insecure border — they crossed legally seeking treatment.

Up till now, the administration and its allies have continued to focus on the alleged threat of infections posed by border insecurity. That focus ignored the fact that the United States was already a source of the virus to Mexico and Central America.

It also ignored that public health campaigns in the border region, not wall-building, were what was needed to protect border-state residents from spreading the virus through normal interactions. The U.S.-Mexico Border Health Commission, set up to carry out such efforts, has been largely idle during the Trump administration, even during the pandemic when it was needed.

On June 23 in San Luis, Arizona, Trump visited a newly built border barrier and said: “It stopped COVID. It stopped everything.”

It didn’t. And it was negligent to think the wall could protect people on either side of the border from a virus.

US Seeding outbreaks around the world

President Trump has spread border-disease alarmism for years. Early in his campaign, in July 2015, he claimed in a statement that “tremendous infectious disease is pouring across the border.”

In December 2018, he tweeted that Democrats “want Open Borders for anyone to come in. This brings large-scale crime and disease.”

So it was no surprise that as soon as coronavirus threatened, Trump and his allies warned migrants would bring it in if his wall was not built. The surprise was, the opposite happened.

Puebla state workers handle an urn holding the ashes of a Mexican who died from COVID-19 complications during a ceremony for 105 Mexicans who died in the U.S.

In the early stages of North America’s pandemic, it was the United States, not Mexico or Central America, that had the biggest outbreaks. Soon, the virus made it into American immigration detention centers.

Even as the disease spread, Immigration and Customs Enforcement kept moving detainees around and sending them to their home countries on deportation flights. Soon our government was seeding outbreaks around the world, as the New York Times reported July 10.

Guatemala’s health minister, Hugo Monroy, told that country’s congress that on one deportation flight, 75% of the deportees were infected. In late April, the health ministry reported that 20% of those confirmed infected in Guatemala were deportees.

Guatemala refused to admit deportees in May but allowed flights to resume in June after the United States began certifying the health of deportees and reducing the number of passengers on flights. Of course, it was too late.

Mexicans demand protection

On March 20, the United States formally closed its border to nonessential travel from Mexico or Canada. It sounded like a severe measure, especially when the U.S. embassy in Mexico City repeatedly warned Americans living south of the border to return home or risk losing the chance.

It turned out not to be that big a deal. U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents have been able to cross into the United States freely through ports of entry, though visa holders must show their travel is essential.

Under the president’s emergency declaration, Border Patrol agents were allowed to immediately return to Mexico anyone caught crossing illegally, which undoubtedly kept some infected people from spreading the virus in the United States.

But Mexico was reluctant to impose any checks, allowing Americans to cross the border freely through the ports of entry. That angered some Sonorans who felt the government was not offering them any protection from the American hot zone.

A Mexican public health official checks the temperature of a driver at a “sanitation filter” checkpoint for COVID-19 in Mexicali, Mexico.

On March 25 and 26, a small group of Nogales, Sonora, residents blocked the main road into downtown from Arizona.

“We wanted Mexico to take more precautions,” organizer José Luis Hernandez said. “We knew that if the infection spread in Mexico, there wasn’t going to be capacity to confront the situation.”

In early May, city officials in Nogales, Sonora, set up sanitizing tunnels — inflatable tubes alongside the road into Mexico. Drivers and passengers were forced to get out and walk through a disinfectant spray called Biozinc.

A motorist is sprayed with the disinfectant Biozinc inside a sanitizing tunnel — inflatable tubes — alongside a road in Nogales, Sonora.

As Arizona’s cases surged in June, Sonora’s did, too, and Sonorans became increasingly nervous about their viral neighbors to the north. Their fears reached a climax as the July 4 weekend approached and they envisioned infected Arizona residents pouring south to visit family or tourist destinations.

Sonoran Gov. Claudia Pavlovich ordered state officials to turn away any travelers from Arizona without essential business in Sonora, though travelers to Puerto Peñasco, or Rocky Point, received a partial exemption.

That raised anger in Sonoyta, the border town on the way to Puerto Peñasco. Carlos Chavez Jaquez, a 21-year-old student at the University of Arizona, has been living with his mother in Sonoyta and organized a blockade on the July 4 weekend.

“The U.S. embassy and our government said only essential travel was allowed in Mexico. But Rocky Point was saying everyone was welcome, come and visit us,” Chavez Jaquez said.

“Everyone is concerned about it,” he added. “We know that Arizona is one of the states with the most cases in the United States.”

“No aceptamos visitas”

Even remote pueblos in northern Sonora have learned that the hard way, by importing infection from Arizona.

Take Sáric, a small Sonoran town about 55 road miles southeast of the border crossing at Sasabe. A well-known Tucsonan, former Sunnyside High School Principal Raul Nido, has made the area his home for most of the last 10 years.

It’s where he lived his first seven years as a child and where his family owned a rural ranch that he began fixing up after retiring from Sunnyside in 2011.

Connections to Arizona brought the virus into Sáric and have changed the close-knit nature of the town, said Nido, interviewed Thursday when he was in Tucson to pick up supplies.

The first resident to come down with the coronavirus apparently got it from attending a quinceañera in Rio Rico, Arizona, Nido said. Indeed, Sonora’s health secretary noted that the 65-year-old had visited Arizona on March 16, got sick six days later and was hospitalized in Nogales, Sonora, on March 28. She ended up dying.

“It sent a chilling effect through the whole town,” Nido said.

A second case occurred in Sasabe, Sonora, and was also connected to Arizona, Nido said. The woman’s daughter was asymptomatic but infected in Tucson.

Despite these illnesses, the rugged residents of Sáric had not yet taken fully to wearing masks and distancing in June when car crashes killed two young men from the area, Nido said. After those deaths, family and friends poured into town from Arizona and Sonora for the funerals. More cases of COVID-19 resulted.

“Then all of a sudden people were wearing masks,” Nido said. “Then the store owners said, ‘We’re not accepting anyone into the store unless you wear a mask.’ ”

The cases imported from Arizona even reduced the residents’ usual social routine of making impromptu visits to each others’ homes, Nido said.

Now, some residents have put signs on their doors saying “No aceptamos visitas” — “We don’t accept visits.”

El Paso Disinfection station and Mexicans Waiting to be de-loused at the international bridge at the US Immigration Station in 1917.

Spreading fears of typhus to Ebola to COVID

Treating immigrants and the Mexican border as sources of disease is nothing new — the idea goes back more than a century.

When the first surges of southern and eastern European immigrants began dominating East Coast arrivals in the late 1890s, the U.S. government began inspecting new arrivals for signs of, as the new federal law put it, “loathsome and contagious diseases.”

At the U.S.-Mexico border, the most dramatic public-health blockade last century was against typhus, a set of bacterial infections spread by lice. An outbreak had occurred in Mexico, and in 1917 U.S. officials began a policy of trying to kill any lice that might be on Mexican people who were crossing the border.

“They tried to stop all traffic between the United States and Mexico,” said John McKiernan-Gonzalez, a history professor at Texas State University and author of a book called “Fevered Measures: Public Health and Race at the Texas-Mexico Border, 1848-1942.” “They gave customs authorities the ability to detain and fumigate people.”

U.S. officials stripped down Mexicans crossing the border and doused them with whatever the lice-killing substance was of that moment. Gasoline, DDT and other harsh chemicals were used. This led to rioting in El Paso in 1917, but the practice went on.

In fact, McKiernan-Gonzalez said, it went on for 20 years after the outbreak was over. Only the demand for labor that came with World War II ended the practice.

In more recent years, every outbreak of an exotic or threatening disease has brought warnings that it would certainly cross the U.S.-Mexico border.

In 2014, it became all the rage among politicians and commentators on the political right to say the Ebola outbreak in West Africa would come through the Mexican border.

Then-Marine Corps Gen. John Kelly, who later became Trump’s chief of staff, warned about it reaching Latin America.

“If Ebola breaks out in Haiti or in Central America, I think it is literally ‘Katie bar the door’ in terms of the mass migration of Central Americans into the United States,” Kelly said.

It turned out to be hype. No migrants with Ebola ever reached the U.S.-Mexico border, and the handful of cases that reached the United States from travelers to Africa were quickly isolated and treated. Just one person died.

Seeking treatment in US

As coronavirus surged in the U.S. Southwest in June, a new argument emerged: It was actually Mexico’s outbreak causing the outbreaks in California, Arizona and Texas, not the reopening of those states after the initial shutdowns, or community spread within and among the states.

In early June, the White House coronavirus task force discussed the idea that travelers from Mexico were causing the surges, USA Today and The Associated Press reported.

Soon the idea spread — it was a way to remove blame from governments that had reopened poorly or prematurely, while refocusing blame on Mexico.

The Center for Immigration Studies, an immigration restrictionist group, has given fullest voice to the argument, referring to people crossing the border for treatment as “COVID refugees”:

“Enough evidence is now on hand that severely ill patients are pouring over from Mexico and adding to the American counts of hospitalization and death, probably coinciding with regular community spread resulting from recent mass protests,” the center’s Todd Bensman wrote.

But I’ve surveyed a half-dozen health-care officials in Texas, California and Arizona and found only one area where they thought people seeking medical attention from Mexico was a significant factor in hospital overcrowding and possibly disease spread — Imperial County, California.

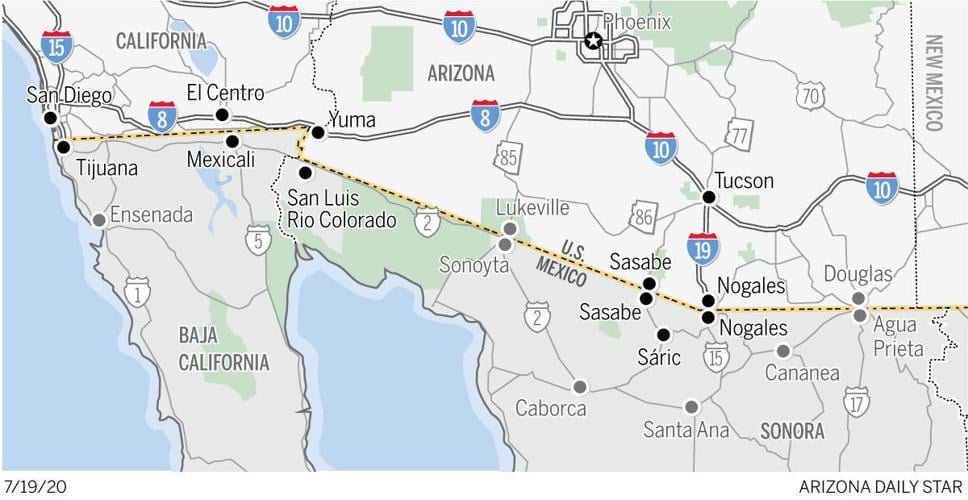

Imperial County, a farming region west of Yuma where El Centro is the county seat, has only two hospitals, but it is across the border from Mexicali, Baja California. That city has more than 1 million residents and experienced a raging coronavirus outbreak that filled hospitals.

Dr. Adolphe Edward, CEO of El Centro Regional Medical Center, told me a surge of patients from Baja California started arriving in May. Although the hospital doesn’t track the nationality of patients, it was apparent that many were U.S. citizens or permanent residents living in Mexico who got sick with COVID-19.

There’s no sign the patients crossed the border illegally, though — the president’s longstanding fear — but that they had permission to cross and sought treatment.

It’s common for American residents of Baja California to seek medical treatment in the United States. What was unusual is that so many needed it at once.

The El Centro hospital became overwhelmed and ended up shipping patients to other hospitals around California, Edward said. While the flow from the south has slowed, the outbreak remains strong in Imperial County.

“The difference between then and today is that I’ve got the state supporting us in terms of staffing,” Edward said. “Every day we wake up and pray that we have enough staff and enough energy to keep going.”

San Diego-Tijuana transmission

Once again, on July 9, Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, penned a letter to federal officials demanding to know how the “unsecured border” was leading to infections in the border region. This time, though, he and his co-signers acknowledged legal crossings might also be a factor.

The experience of San Diego and Tijuana shows that normal interactions from legal crossings is what has kept the disease flowing across the international line, just as it did between states like New York and New Jersey, or northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico.

The region’s outbreak started in mid-March in San Diego, said Dr. Andres Smith, medical director of the emergency department at Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center.

Within a week or so, the virus began spreading in Tijuana, where Mexico’s worst outbreak of the time took hold in April and May, said Smith, who is also president of Tijuana’s Red Cross emergency-medical service.

People sit at a beachfront restaurant, left, as children carrying ice cream pass, Friday, May 22, 2020, in San Diego. Millions of Californians are heading into the Memorial Day weekend with both excitement and anxiety after restrictions to control the spread of coronavirus were eased across much of the state.

“It did reach a point where it got very scary for them because it looked like it was getting out of control,” said Smith, who also worked in Tijuana’s Hospital General in May.

In Tijuana now, “things are much better. The concern is that now in the South Bay of San Diego, and around San Diego, cases are going up again,” he said. “Now that Tijuana is better controlled, will the effect of San Diego create an effect in Tijuana?”

Those who think of the international border as a line that should stop the virus are missing the reality of the region.

“People move back and forth between San Diego and Tijuana,” Smith said. “Especially (from) the South Bay there’s a large proportion of Mexican Americans who have family on both sides. They have businesses in Tijuana. So they go back and forth.”

Anywhere outbreaks occur, it’s that movement of people, their interactions, and their lack of precautions that keep spreading the disease.

“People keep trying to throw the other guy under the bus,” said Dr. Edward, of El Centro. “Mexicali would say the U.S. is bringing the COVID to us, and we’re saying ‘You guys are bringing the COVID to us.’ And Yuma is saying ‘You had the COVID, and you brought it to us.’ I don’t think the virus checks on borders. I don’t think it checks on whether it’s in Arizona or California.”

Or whether it’s in Mexico or the United States.

Public health action lacking

The fixation on border security as a key factor in the pandemic has distracted from what should actually be done. That is: focus strictly on public health measures that keep people from infecting each other in their day-to-day lives.

“You need to build a public health infrastructure on both sides of this border because they’re connected in really difficult ways to disentangle,” said McKiernan-Gonzalez, the Texas State University historian.

While Trump has fixated on building more border wall to stop the virus, an organization founded 20 years ago to deal with disease in the borderlands has languished. For around four years, the U.S.-Mexico Border Health Commission has been essentially inactive, Arizona’s two members of the commission told me.

“The commission has been non-participative in this event,” said Robert Guerrero, the director of Arizona’s Office of Border Health and the state health department’s delegate to the commission.

The equivalent organization on the Mexican side, the Comisión de Salud Fronteriza México-Estados Unidos, has remained active, Guerrero noted, hosting virtual seminars on the pandemic.

Guerrero himself has been in constant communication with his counterparts in Sonora, and each of them produces a daily report for the other, he said. While that state-to-state relationship has been good, the borderwide communication that existed during the 2009 outbreak of H1N1 flu has not been there during this year’s pandemic.

“In 2009, when the pandemic hit, both sections got together, and we held a huge conference in Hermosillo,” he said. “It brought together HHS, CDC and their (Mexican) counterparts. It was very productive in developing cross-border messaging and whatnot. But right now the commission has not.”

While the commission has been AWOL, the builders of the border wall have been busy, coming to Southern Arizona from around the country, throwing up barriers as fast as possible. Two of them, staying in Ajo, became infected, or brought infection from elsewhere.

It turns out that border security, as Trump and his allies envision it, is not health security at all. The pandemic that has raged in Arizona and other border states while Trump rushed to build more wall has proved that.