As Election Day nears and polls suggest he’ll lose the presidency, Donald Trump has started hammering “criminal aliens” again.

For Trump, it’s a return to form. When he rode down that golden escalator on June 16, 2015, to announce his run for president, he knew how he would separate himself from the 16 other Republican candidates.

He would go hardcore on immigration, talking tougher and more crudely about migrants and the border than any other candidate. He did it that day, setting a pattern for his presidency.

“They’re bringing drugs,” Trump said of undocumented migrants that day, in his infamous refrain. “They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

To justify his harsh border and immigration policies, Trump and allies repeatedly associated immigrants, especially undocumented ones, with crime. He would pound that linkage home until his policies seemed necessary to keep Americans safe.

Migrants and crime, crime and migrants.

Trump mostly laid off that tactic in this year’s campaign, preferring to highlight American rioters as a threat, but he has suddenly begun raising the specter of foreign criminals again.

Late Friday night, Trump issued a proclamation declaring Sunday, Nov. 1, a “National Day of Remembrance for Americans Killed by Illegal Aliens.”

The problem is, the association he’s making is not born out by research. The presence of foreign-born, and even specifically of undocumented, people is not associated with higher crime rates in the United States.

Some studies even show that the more immigrants in a given area, including undocumented ones, the lower the crime rates.

But of course, some foreign-born people do commit crimes, and Trump has used those cases. He made an argument that was not based in statistical probabilities but on alarming anecdotes.

To understand why, go back to the 2015-2016 Republican race. Trump’s team knew the appeal would work with a significant part of the Republican primary electorate, who were angry about the mealy-mouthed ways that candidates like Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush were talking about immigration.

One of Trump’s top advisers early in the campaign, Sam Nunberg, told me Trump tried to contrast his views with the “chamber of commerce” idea that even migrants illegally in the country are good and a net benefit.

“All we hear is people saying, ‘These are good people. They’re here for a good life. They want to do jobs others don’t do.’ And we wanted to say, ‘Oh, yeah? What about the other ones?’” Nunberg said.

“You want to go into generalities, well what about these specifics? What about this murderer? What about this rapist? What about this drug dealer?”

Bolstering their point, a killing occurred just two weeks after Trump’s announcement that featured all the fears Trump raised. A Mexican man — in the country illegally after having been deported and rearrested in a sanctuary city, San Francisco — was accused of shooting and killing a young white American woman, Kate Steinle. The crime, of which the migrant was acquitted in 2017, became a flashpoint.

“This senseless and totally preventable act of violence committed by an illegal immigrant is yet another example of why we must secure our border immediately,” Trump said in a statement days after Steinle’s death. “This is an absolutely disgraceful situation, and I am the only one that can fix it.”

A man walks past a memorial to Kate Steinle in San Francisco in 2017. The killing of Steinle, of which a migrant was acquitted, became a flashpoint for the Trump administration.

“Angel Families” take center stage

Much of the Republican electorate was thrilled by Trump’s promise. That showed as he rolled through state after state in the 2016 primary elections.

The rest of the country, though, was not as receptive. Just as there is a persistent strain of anti-immigrant sentiment in America that rises and falls with the times, there is a persistent strand of pro-immigrant sentiment.

Then the so-called Angel Families entered the political scene. These were the parents and relatives of people killed by people in the country illegally. They heard Trump’s message, and they reached out.

“They contacted the campaign organically,” Nunberg said.

The alliance that resulted between Trump and those victimized by “criminal aliens” colored the rest of his campaign and much of his presidency.

He upheld the stories of people like Steinle and family members like Mary Ann Mendoza as what results when you don’t impose strict policies on the border and on immigration generally.

President Trump listens as Mary Ann Mendoza, who lost her son Brandon when he was killed by a drunk driver who was in the United States illegally.

At the Republican National Convention in 2016, Trump introduced the country to victims’ parents, like Mendoza.

Her son, Brandon Mendoza, was a Mesa police officer. In 2014, a man in the country illegally, Raul Silva Corona, was drunk and high when he sped recklessly for a half-hour around Phoenix-area highways, finally striking Mendoza’s vehicle head-on. Both of them died.

“My son’s life was stolen at the hands of an illegal alien,” Mary Ann Mendoza said at the convention. “It’s time we have an administration that cares more about Americans than about illegals. A vote for Hillary (Clinton) is putting all of our children’s lives at risk.”

Anecdotes, not data

In rhetoric, there’s a name for the sort of argument Trump was making through these examples. “synecdoche” (pronounced “suh-NEK-duh-kee”) means “the part that stands for the whole.”

Jennifer Mercieca, a professor of communication at Texas A&M University, told me about that and other rhetorical strategies Trump used in interviews in late 2019 and early 2020. Since then, she has published a book called “Demagogue for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump.”

This was one of his more effective, ingenious campaign communication strategies, she said.

“The reason for that is that at first he made a very general claim — ‘They’re all rapists, they’re all drug dealers and some I assume are good people,’ ” Mercieca said. “Then he started using examples from testimonials from the affected families.”

“A synecdoche is really powerful. It’s a representative anecdote. You can mislead an audience by making it seem like the anecdote is more representative than it really is,” she said. “He’ll provide you with three or four examples, so it seems like an accumulation of evidence.”

That, she said, allowed Trump “to paper over the differences between what the data show and what the examples show. It’s not that the stories weren’t true. The stories were true, but they weren’t representative.”

The Trump White House saw the power of those stories, asking the Border Patrol sectors to provide them and the Department of Homeland Security to publicize them.

David Lapan, the first DHS spokesman under Trump, told me presidential adviser Stephen Miller wanted Lapan to spotlight crimes by immigrants.

“I was in a meeting with him where he said, ‘We need to get more stories out about immigrants harming Americans, killing people,’” said Lapan, who was in the job for the first seven months of Trump’s term. “‘We need more stories to highlight the criminal activities of immigrants.’

“We came out of the meeting with Stephen Miller and said, ‘We aren’t going to do that.’ It wasn’t our role to cherry-pick stories to highlight.”

Research undermines crime claims

The foreign-born population, whether in the country legally or illegally, does not have a greater propensity for crime, numerous studies have shown.

In fact, research published in 2018 reviewed 51 studies of the linkage between immigration and crime published from 1994 to 2014 and found a very weak negative association. In other words, the presence of immigrants in any given area is weakly associated with less crime, not more.

The researchers doing these studies note they’re talking about correlation, not causation. In other words, they can’t say the presence of more foreign-born people causes less crime — just that their presence at greater degrees is not associated with more crime.

The most recent research, published Oct. 3 in the Journal of Crime and Justice, zeroed in on the relationship between undocumented residents specifically, not just the foreign-born generally, and crime in metro areas. It came up with the same result: More undocumented people in a metro area means the same amount of or even less crime.

Robert Adelman, the chair of the sociology department at the University at Buffalo, led that study as well as another one, published in 2017, that analyzed the effect of the presence of foreign-born people on crime rates over decades.

“It’s pretty clear from the data that with both the foreign-born population and, in the latest study, the undocumented population, we don’t find an effect on violent crime rates,” Adelman told me Wednesday.

With respect to property crime, they found a weak negative effect — in other words, more undocumented people in a given area was mildly associated with less property crime.

“We’re not saying immigrants or undocumented immigrants don’t commit crimes. That’s not what the study is about,” Adelman said. “People from all groups commit crimes, including undocumented immigrants.”

Pima County Sheriff Mark Napier said sheriffs in other parts of the country assume the jail in this border county must be filled with people in the country illegally, but that’s not true.

“It usually runs about 5% to 6% of the population of the Pima County jail at any given time (that) is comprised of people that are undocumented,” Napier said.

Pima County Sheriff Mark Napier said sheriffs in other parts of the country assume his jail is filled with people in the country illegally, but that’s not true. “It usually runs about 5% to 6% of the population of the Pima County jail,” he said.

“About 3% of the population of the jail at any given time are subject to ICE detainers,” he said, meaning Immigration and Customs Enforcement has identified them as subject to removal.

The probabilities, of course, are no solace to those who are victimized. Members of the Angel Families often make the argument that their victimized relative would still be alive if it weren’t for insecure borders. That’s true, as far as it goes.

But the same reasoning applies to almost any crime: It wouldn’t have happened but for the circumstances that allowed the perpetrator to do it. Border insecurity, in that sense, is like drug use or drunk driving or lax gun laws or even parental neglect and abuse. Without them, the criminal wouldn’t have done what he did.

Trump turns to gangs

Trump’s initial focus on Angel Families gradually transitioned into a fixation on the idea that members of criminal gangs, especially Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, were embedding themselves with asylum seekers from Central America.

“Many Gang Members and some very bad people are mixed into the Caravan heading to our Southern Border,” he tweeted on Oct. 29, 2018.

There’s much to unpack in Trump’s claims. For example, there are the facts that MS-13 is a U.S.-born gang exported to El Salvador from California, and that it never had been a significant player in transnational crime, contrary to what Trump claimed.

But perhaps the most important aspect of his focus on MS-13 was that it justified building border barriers and clamping down on asylum seekers at the Mexican border.

“We’re here today to discuss the menace of MS-13,” Trump said May 23, 2018, at an event on Long Island, N.Y., where he introduced parents of children killed by the gang. “It’s a menace. A ruthless gang that has violated our borders and transformed once-peaceful neighborhoods into bloodstained killing fields.”

Twice in 2018, caravans of asylum seekers began walking toward the United States from Central America, which renewed Trump’s use of the rhetoric of migrants as criminals.

“He needed the plot points to move the narrative along,” Mercieca said. “The caravan provided him with an opportunity to talk about this as an imminent threat in 2018. ‘These caravans full of people are attacking the nation.’ That was really helpful.”

His rhetoric suggested gang members were pouring across the border in the caravans, claiming asylum, but that was hyperbole.

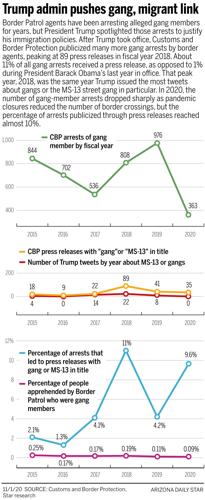

In the last six years, 2019 was when U.S. Border Patrol agents caught the most people they labeled as gang members: 976. That was one-tenth of 1% of the total number of people the Border Patrol apprehended that year, 859,501.

In other words, in the worst recent year, only 1 out of 1,000 Border Patrol apprehensions was, by the agency’s designation, a gang member.

After Trump took office, Customs and Border Protection began announcing the arrest of gang members much more regularly. In fiscal year 2018, the Border Patrol arrested 5% fewer gang members than it had in 2015, but CBP put out five times as many press releases announcing in their titles the arrests of “gang” or “MS-13” members.

A former DHS spokesman said presidential adviser Stephen Miller, above, told him: “We need to get more stories out about immigrants harming Americans, killing people.”

It’s probably not a coincidence that 2018 was also the year President Trump focused his rhetoric most sharply on gang members crossing the Mexican border. That year, he tweeted 22 times about gangs, or MS-13 in particular, as compared to 14 times in 2017, eight times in 2019 and zero times so far in 2020.

Victims of immigrants

As Trump and his allies have pushed to link migrants with crime, he has received steady pushback and mixed results on that narrow issue.

But the rhetoric has helped him justify and enact broader immigration changes, such as forcing asylum seekers to remain in Mexico while awaiting their asylum cases; separating migrant parents from children; slashing refugee admissions; and, of course, building border wall.

Through a variety of maneuvers, he has also succeeded at cutting annual legal immigration levels from about 1 million in 2015-2016 to about 600,000 in 2018-2019.

As one of his first acts, on Jan. 25 2017, Trump issued an executive order that included a crackdown on sanctuary cities and the establishment of an office serving the victims of crimes committed by “removable aliens.”

It was named the Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement (VOICE) office and served dual purposes. One was the defensible aim of providing information to victims of crimes by undocumented people about the perpetrator’s status in the immigration system. The other was to make that familiar rhetorical linkage: immigration and crime, crime and immigration.

“The rationale that made sense of it to me was, because the immigration system wasn’t the same as the criminal justice system, having a way for victims’ families to be kept apprised of what was happening,” said Lapan, the former Homeland Security spokesman.

“On the flip side, what I wasn’t comfortable with was elevating this to make it seem like immigrants were committing crimes above the levels of nonimmigrants, which we know is not the case.”

Democrats pushed back on the establishment of the VOICE office, but it has persisted quietly, not posting a report on its activities since the first quarter of fiscal 2019.

They had more luck with Trump’s efforts against sanctuary cities, from which the same 2017 executive order aimed to withhold federal grants. Cities targeted by the measure sued and have so far won their cases in federal appeals courts, blocking Trump from withholding money.

Iowa murder’s aftershocks

In the middle of Trump’s busiest year of linking migrants to crime, July 2018, 20-year-old Mollie Tibbetts disappeared while jogging near her small Iowa hometown.

A month later, police arrested a young Mexican man, illegally in the country and working at a nearby farm. Prosecutors charged him with Tibbetts’ murder.

Cristhian Bahena Rivera was charged with first-degree murder in connection with the death of Iowa student Mollie Tibbetts in 2018. The trial has been delayed to January.

The outcry was immediate and predictable. Trump blamed her death on Democrats, a “party that puts criminal aliens before American citizens.”

“What happened to Mollie was a disgrace,” Trump said. “We mourn for Mollie’s family.”

But Mollie’s family wasn’t having any of it. In an op-ed, her father decried those who were trying to use her as a “pawn” in promoting a “racist” agenda.

“The person who is accused of taking Mollie’s life is no more a reflection of the Hispanic community as white supremacists are of all white people,” Rob Tibbetts wrote.

Her mother, who was separated from Mollie’s father, went further. Authorities had raided the farm where the accused killer lived and worked, and other Mexican farmworking families living there had fled. Mollie Tibbetts’ mother, Laura Calderwood, took in the son of one of those families, a 17-year-old who wanted to stay and graduate from high school in the town that was his home.

It was part of a persistent pushback in society toward Trump’s immigration and border policies.

The breadth of that point of view became evident this year in a Gallup survey about immigration, which has been asking Americans the same questions since 1965.

During Trump’s presidency, public opinion of immigrants has been improving. In June, for the first time in the history of that poll, more Americans said they think the number of immigrants to the United States should increase than said it should decrease, by 34% to 28%.

One more time with migrant crime

Trump’s focus on “criminal aliens” waned somewhat after 2018. This year, he’s stopped tweeting about migrant gang members, and instead of attacking sanctuary cities for their immigration policies, he found another angle.

The new big threat Trump cites is antifa. After the unrest over police violence this summer, Trump designated New York City, Portland and Seattle as anarchist cities and threatened to remove funding for this new reason.

The Wall Street Journal reported immigration dropped far down the list of issues Trump talks about. Some of Trump’s allies began asking, what happened to immigration?

But as the campaign winds down, the siren song of the criminal alien is inevitably drawing Trump and his allies back.

Trump said of Democrats, during a rally in Florida on Oct. 23, “They want to unleash the violent rioters, criminal aliens, MS-13 killers.”

In his new proclamation, he declared that “Americans who are killed by illegal aliens are no longer forgotten, and we are ensuring that they will not have died in vain.”

The Department of Homeland Security’s top officials have been crisscrossing the country, brazenly campaigning for the president on the taxpayer dime. The acting commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, Mark Morgan, warned of an “illegal invasion” if Joe Biden is elected.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement even put up six billboards showing the mugshots of men along with a criminal charge like “burglary” or “assault.” Each person is labeled a “criminal alien” and each sign carries the slogan “Sanctuary policies are a REAL DANGER.”

The billboards went up, of course, in a state Trump won in 2016 and is struggling to win again this year — Pennsylvania.

It’s one late test of whether the threat of the foreign criminal can still win elections.