David Slutes apologized for the noise coming from the chapel of the old Benedictine Monastery that late March Tuesday morning.

The drone of drills and hammers clanking from workers chiseling away at the tile echoed up to the second-floor office where Slutes and longtime Sidewinders bandmate Rich Hopkins sat side by side on a worn couch. The office will soon be a “green room” for La Rosa, the 500-seat venue that Slutes is developing with partner Charles Levy.

Slutes was taking time out of the behemoth reconstruction project to share memories with Hopkins about their 1980s-’90s alternative rock band, which marks its 40th anniversary with a concert at Hotel Congress on Saturday, May 3.

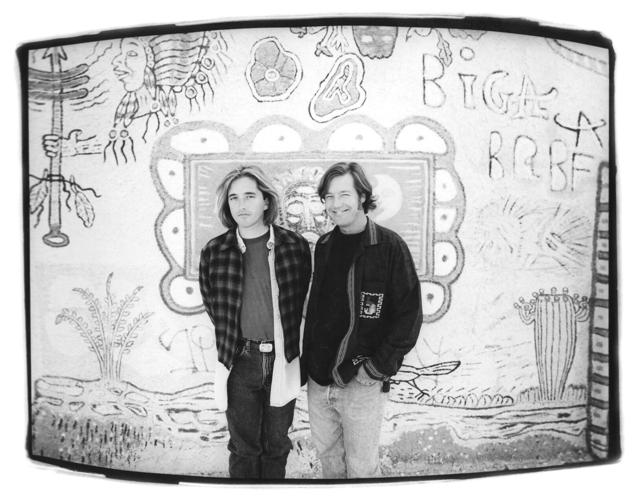

David Slutes, left, and Rich Hopkins were the leaders of Tucson’s 1980s-90s alt-rock ensemble the Sidewinders.

But this time, they weren’t being asked about the glory days after Sidewinders landed a major label record deal in 1989, toured coast-to-coast including famously having Pearl Jam open for them, and had two songs on the Modern Rock charts.

For the first time in a long time, someone was asking them about their breakup.

If you Google “Tucson Sidewinders band breakup,” you’ll find references to the 1991 lawsuit by a North Carolina cover band with the same name.

The suit played a big role in their demise, but there was much more to the story.

There were crushed egos, outsized dreams and rediscovering what really matters: The music.

Although they technically split up in 1994, the Sidewinders never really split. The band has played dozens of local shows including at HoCo Fest, which Slutes curated when he was the Hotel Congress music director.

Before there was an ending, there was a beginning

The Sidewinders was a work in progress in early 1985, with a revolving door of players who were on-again, off-again. That’s when David Slutes kind of inserted himself into the band that Rich Hopkins started a year earlier.

The two were casual acquaintances; in Tucson’s mid-1980s music scene, everyone knew everyone. They had never performed together when Hopkins, who was in his mid-20s, reached out to Slutes, still a teenager, to use the younger musician’s home studio. Hopkins wanted to record instrumental tracks and have the band’s singer record the vocals the following week.

Rich Hopkins, left, and David Slutes pose for a photo in the confessional inside the old Benedictine Monastery that Slutes is renovating as a concert venue.

When Hopkins returned to the studio a couple of weeks later, Slutes had a confession.

“Don’t know if you’re gonna like this or not,” he said, and hit play.

Slutes had recorded vocals to the track.

“Literally, just like that, it was perfect,” Hopkins said.

Hopkins asked Slutes to join the five-piece band and for the next couple of years, the Sidewinders played the local and regional rock scene, trying to get a foothold among the likes of the popular Naked Prey and Giant Sand garage bands that dominated the scene.

David Slutes, right, and Rich Hopkins talk about their band, the Sidewinders. From the first song they cowrote, “I Should Have Told You,” on May 3, 1985, Hopkins and Slutes realized they made a good team.

Hopkins wasn’t convinced they were good enough — “We could barely really play our guitars,” he recalled. They also had trouble keeping lead guitarists.

But songwriting was a different story. From the first song they cowrote, “I Should Have Told You,” on May 3, 1985, Hopkins and Slutes realized they made a good team.

“We just sort of pushed ahead and kind of wrote stuff,” Slutes explained.

“The real change to me was when we said, screw it. Let’s just break it down to the four of us. I’ll switch over to rhythm, you be lead,” Slutes said and Hopkins nodded. “We started becoming the thing and we started writing better, and our focus was better. We got simpler. Once we broke it down to its essence, it was a lot better.”

Rich Hopkins, left, and David Slutes have remained friends for 40 years, despite some rocky moments early on.

In 1988, the Sidewinders released “¡Cuacha!,” a self-produced album they recorded at the Sound Factory in Tucson and mixed in Los Angeles with Eric Westfall, who had worked with Giant Sand and River Roses.

That year, they decided to take a shot at SXSW (South By Southwest) in Austin, Texas, the annual indie music festival that has launched dozens of careers including John Mayer, The Strokes, Ellie Goulding and M.I.A. North Carolina record producer Jay Faires was in the audience and after the show, he introduced himself. He was starting an indie label called Mammoth Records. Did the band have anything ready to release? he asked.

Sidewinders had already started recording their second album, “Witchdoctor,” which Faires agreed to release as Mammoth’s debut. The album dropped in 1989 and the title song landed at No. 18 on the Modern Rock charts, becoming the Sidewinders’ first nationally charted single.

Three months after its release, Mammoth hosted a showcase with RCA Records, which loved what they heard; they bought “Witchdoctor” and re-released it under RCA/Mammoth.

RCA sent the band on the road to open for bigger acts including The Replacements and do smaller headlining shows. When the video for “Witchdoctor” landed on MTV, the band saw their small club crowds double in size.

“I remember that first show after our first video was on MTV went from 300 people to 700 people,” Slutes recalled. “We were playing Tipitina’s in New Orleans ... and I go, ‘What’s going on?’ ‘Oh, we saw your video. Sounds great.’ This is like real rock star stuff.”

In 1990, RCA/Mammoth released “Auntie Ramos’ Pool Hall,” which gave the band its second hit single, “We Don’t Do That Anymore.” The song landed at No. 23 on the Modern Rock charts.

Then came the middleman

When you’re in your early 20s and the record execs are promising you a gold-paved path to glory, you nod your head and go along.

Until you realize you’re not sleeping in fancy hotels and being chauffeured in limos; you’re couch surfing with friends and can’t make ends meet with the small salary from the label.

In early 1990, Hopkins and Slutes confronted Faires. They were tired of being broke, so Faires, encouraged by RCA, loosened up the purse strings. RCA gave Faires a nudge on the issue, but RCA wasn’t interested in fighting the Sidewinders’ battles; they needed a manager, someone who could advocate for them and be the go-between with the label.

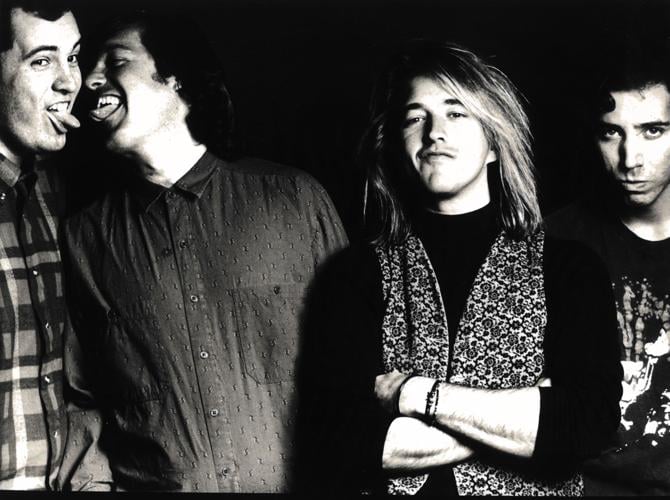

Sidewinders founder Rich Hopkins, far left, and frontman David Slutes, second from right, were living the rock ‘n’ roll dream in the late 1980s.

RCA set them up with Alex Hodges, who represented Otis Redding, the Allman Brothers Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Hodges was an older Southern gentleman who said he saw good things in the band so Hopkins and Slutes signed on. But before the ink had dried, RCA soured on the deal. Turns out they didn’t like Hodges’ assistant, Slutes recalled.

“We had to go back to them and renege on that deal,” Hopkins said. “I personally felt like that was the No. 1 mistake we made. But when the record label says jump, you jump.”

“We’re young. We’re kids,” Slutes added. “We’re Tucson kids that are doing this thing, that don’t know anything about this business, and we are just very intimidated by it, very impressed by it. So they can bully us around.”

They were checking out other manager candidates when they met Mike Lembo.

Mike Lembo was big and brash, an outsized personality who sucked the oxygen out of every room he entered.

“He was such a different beast,” Slutes said, the type in the industry “who just comes in and bullies everyone.”

“He was like a bull in a china shop,” Hopkins said. “Personally, me and him did not see eye to eye on anything because I wanted more of a touchy, feely person. ... Mike came in and he goes, ‘You know, those two albums, ‘Witchdoctor’ and ‘Auntie Ramos’? They suck compared to what we’re going to do’. And I had a lot of pride for what we do. ... Him and I really clashed a lot.”

“That’s when some of the friction started happening,” he added.

At a meeting with RCA execs in New York City, Lembo insulted every person at the table as he made a play that the band was shopping a new deal.

“I mean, we didn’t know. And he says, ‘Listen, we’re going to get a real deal. You’re going to get real money for this next one’ and all those things were true,” Slutes recalled. “All the things he said were true, tons more money. Great. I mean, budget for our next record was half a million dollars instead of $10,000. But it also sort of sucked our soul.”

“Yeah, he did the things that he said, but it left me feeling like this isn’t my band anymore,” Hopkins said, recalling how Lembo drove a wedge between him and Slutes. “Everything was a fight with Mike.”

And then came the lawsuit.

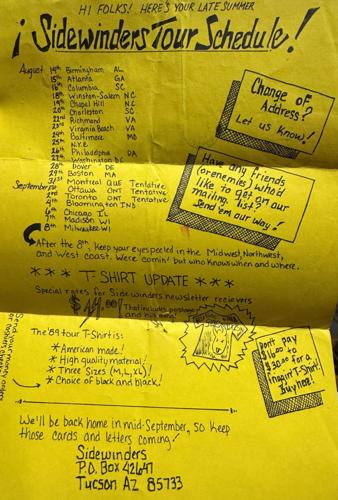

In the late 1980s, early 1990s, when the Sidewinders toured all over the country, then sent their Tucson fans fliers letting them know where they could see them.

Everything was going so well ... until it wasn’t

Thousands of miles from Tucson, a North Carolina cover band named Sidewinders was packing dance halls in neighboring Southern states and in Canada.

Their claim to fame was once appearing on “Star Search,” but the band, which formed in 1978, had never released an album or struck out on a career that didn’t involve playing other artists’ music.

But RCA, upon learning of the band’s existence, decided their name could be confused with the Tucson-born Sidewinders.

So the label filed a cease and desist letter.

The North Carolina Sidewinders responded in 1991 with a lawsuit arguing that they had rights to use the name since they had it first.

Hopkins and Slutes found themselves in the middle of a fight they had no interest in pursuing.

“They were a cover band doing bars up and down the East Coast, doing covers, nothing to do with what we were doing,” Hopkins said. “And somehow RCA picked this fight. And then Lembo comes in, and Lembo sees all the red flags, and that’s when he just took it down, the RCA deal, and he goes, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll get you a better deal’.”

The better deal came two years later when the suit was settled. The Carolina Sidewinders got to keep the name and the Tucson band had to rebrand.

Hopkins came up with the name Sand Rubies and Lembo got them signed to Polydor/Atlas, which released an EP and Sand Rubies’ eponymous debut in 1993.

But the strain of the lawsuit and having to start from scratch and the disagreements with Lembo quickly took their toll.

“That was a tough time because I remember I was married, I had a little baby girl and then we were going to go out on the road on that tour,” Hopkins said. “I just felt like David and I just stopped communicating.”

The band spent most of 1993 touring the record.

Early the next year, they were done.

The breakup, the make up

Funny thing about breakups; sometimes forever turns out to be “for now.”

Two years after they said their peace, let all the ugly that was bottled up for those last couple of years come out in the open, Rich Hopkins and David Slutes arrived at an unspoken truce.

It happened at Hotel Congress.

“I’ll never forget when I went down to Congress and Dave was playing there, and I just remember seeing you out in the audience, and we really connected,” Hopkins told Slutes, choking up as he spoke. “And I just remember I was like, man, I’m so sorry that this shit happened.”

By 1995-’96, the Sidewinders were playing a few local shows here and there. Nothing full-time or overly ambitious; Hopkins had his band the Luminarios and Slutes had a job with Hotel Congress booking shows into Club Congress.

But being back on the stage with no expectations, just creating music for the love of music, put their chase for rock ‘n’ roll fame into clearer focus.

“We had a bigger, deeper bond. We loved our music,” Slutes said. “It’s like having a divorce and all our songs are little, beautiful babies. And we gotta raise them together.”

The band never officially split up and it never officially reunited; it just existed.

From 1996-’99, Sand Rubies released a live album and two studio albums on Hopkins’ San Jacinto Records label. They toured the country and abroad, and played local shows, reintroducing themselves in a fast-moving music world that is quick to forget and move on.

Then in 2002, they released “Goodbye: Live at Alte Malzerei.” It was goodbye, for the most part, although the band reunited several times in the years since for milestone concerts under the name Sidewinders.

“I don’t think our story’s really unlike anybody else,” Hopkins said. “There was a lot of things, missteps, of course, but we’re human beings; we made mistakes. But you know, we also learned from them, too.”

“Our lives have sort of pivoted off this thing, you know? I love this guy,” Slutes said. “(Hopkins) is like my brother. I’ve said this all along. We didn’t grow up together but boy, he’s so important in my life. That’s what we got to get that other bands don’t get. We got to get that.

“We got to have this many years after of just appreciating each other, appreciating the work that we put in and all the music we made, and it’s just wonderful.”