A bell chimes. Candles flicker. Sunlight streams through an open roof.

In DeGrazia’s Mission in the Sun, Our Lady of Guadalupe looks on, her gaze an invitation to sit, pray and reflect.

Ettore “Ted” DeGrazia built the chapel to honor Father Eusebio Francisco Kino and dedicated it to Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“DeGrazia claims he wasn’t a church-going man, but he was a very religious man and was brought up Catholic,” says Lance Laber, the executive director of the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun. “The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe is just very special to Catholics of the Southwest and of Mexico.”

The feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe on Dec. 12 celebrates the appearance of the Virgin Mary to Juan Diego, an indigenous peasant newly converted to Christianity. In 1531, she is believed to have appeared to him and expressed her desire for the construction of a church on Tepeyac Hill in the area of modern-day Mexico City.

In anticipation of her feast day, the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun hosts a festival each year in her honor, this year on Sunday, Dec. 6.

Laber calls her “an icon of the Southwest.”

And for good reason. She is everywhere.

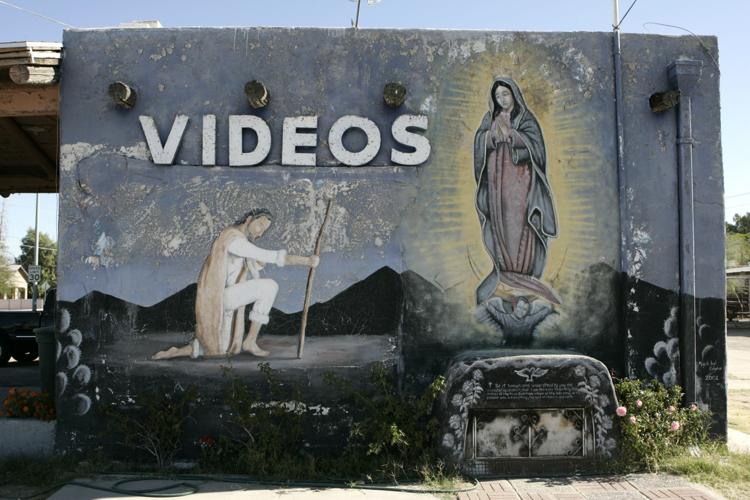

Our Lady of Guadalupe appears throughout Tucson — in churches such as Mission San Xavier del Bac, at the base of Tumamoc Hill and on a mural in the Menlo Park neighborhood.

The Virgin of Guadalupe, as she is also called, shows up on candles and clothing and in places of personal devotion.

This dark-skinned Lady has been called empress, patroness and mother of Mexico and the Americas.

“Since she appeared in the Americas, it is what would be considered a regional devotion,” said Monsignor Raúl Trevizo, the pastor at St. John the Evangelist, 602 W. Ajo Way. “She spoke to the reality of the people of Latin America and the Southwest.”

In Tucson, devotion to the Virgin has been passed down through the generations, culminating on Dec. 12 — the feast day in her honor.

Even those who don’t know the story of Our Lady of Guadalupe relate to her as an intercessor. She is “someone to whom you pray, and you know she will take care of your prayers before God because she has a privileged place before God,” Trevizo says.

To Teresa Mancha, Our Lady of Guadalupe is dear. She learned that from her mother, who moved to the United States from Mexico in the 1940s.

Always, the family had an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe in their home. Always, they thanked her for the blessings their family received.

“We have been blessed to have no major problems,” Mancha says. “That all came from my mother, because her example was to be praying the rosary and praying to her, and she had so much devotion that she died on Dec. 12, the day of Our Lady.”

Mancha says one of her sisters found their mother on her deathbed with her rosary.

“We turn to (the Virgin) and ask her for guidance, and I believe that is the reason why everyone in our family has achieved so much,” says Mancha, who is the costume chairman for the Tucson Desert Harmony Chorus. “My father was educated to the fifth grade and migrated in the ’40s. We now have (in the family) doctors, nurses and lawyers.”

Sister Esther Calderon, too, traces her current devotion to family tradition. She remembers the vigils the night before the Dec. 12 feast. People visited the family’s home in Klondyke, near Safford, and the flowers decorated Our Lady of Guadalupe’s image.

Now Calderon, a sister of the Dominican Sisters of Peace, lives in a home called Casa Guadalupe — named such by her religious order. Images of the Virgin fill the home she shares with Sister Corina Padilla.

When Calderon runs Bible studies in prisons, inmates sometimes give her drawings of Our Lady.

Years ago, the father of one of those men built the small shrine that now protects a statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe in front of the sisters’ home. When the man’s son was released from prison, the son returned to repaint the weathered statue for the sisters.

“Her appearance was in Mexico, so the Mexican people have a really deep devotion to her,” Calderon says. “I think that’s where we get it.”

The traditions revolving around Our Lady of Guadalupe are both personal and ecclesiastical.

The night before the feast day, families might gather at home and in churches to pray the rosary and wait for dawn.

“Then, at daybreak, they would sing to Our Lady of Guadalupe what we call ‘Las Mañanitas,’ ” Trevizo says. “It’s a Mexican song and a festive song in which you greet people while celebrating their birthdays.”

After a night of prayer, morning comes with food and song.

“We don’t stay up until 5 a.m. for ‘Mañanitas’ (in church),” Trevizo says. “But after midnight, we serve food and drink hot chocolate.”

The next day, the parishes celebrate a Mass for Our Lady of Guadalupe. Other traditions include dramatizations of her appearance to Juan Diego and prayer gatherings and processions in the nine days leading up to the feast day.

“It’s nine days of prayer, and it recalls the nine months that the Virgin Mary was pregnant with the child Jesus,” Trevizo says.

In Tucson, even some without Catholic backgrounds identify with the Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“It’s an image that people understand beyond the sense of their religion, and they understand it from an archetypal human point of view of motherhood and protection,” says Susan Gamble, a practicing Episcopalian and owner of Santa Theresa Tile Works.

Gamble considers herself a “border dweller,” and she and the other artists at Santa Theresa Tile Works often draw on the region to inspire their work.

Tile Works artist Kristine Stoner created one of Gamble’s favorite depictions of Our Lady of Guadalupe as a commission for the Pio Decimo Center.

“I can imagine every young mother alive right now, especially an immigrant mother, can identify (with Mary),” Gamble says. “And the grace and dignity that she had — people can aspire to have that much love.”

Gamble sees her as both a religious and cultural symbol.

“That’s where I find her as an inspiration,” she says. “Be it a literal story or a non-literal story, I don’t care. I don’t debate that. The point is that she is woven into our fabric.”