The day after their son’s funeral, Martha and William Wills stepped into his shoes to put on the 27th conference by the Racial Reconciliation Community Outreach Network.

He would have wanted it that way.

Their son, the Rev. William O. Wills Jr., started the conference in 1987 out of a desire to see racial and cultural unity among Tucson’s churches.

The Willses, now in their 80s, expect hundreds of people to attend the 29th conference, which kicks off on Thursday. For two years they have continued without their son to carry on his legacy.

And Tucson is better for it.

•••

Although Martha Wills, 86, grew up in church, she never gave much thought to the interplay between Christian communities and race.

She attended a segregated school and learned to “stay in your place … because you didn’t want to fight, didn’t want to get killed.”

After becoming a licensed practical nurse, she met William while they both served in the Air Force. His childhood, unlike hers, inspired their son.

Growing up in New York City, William participated in a church outreach program that brought together children from New York and Vermont to interact in interracial settings.

“For a lot of people, it was the first time they had any type of relationship with black youth,” William, 83, says of some of the white children. “I don’t think we had any preconceived notions, basically because our schools were integrated.”

William’s career in the Air Force took the family around the country and to England. Wherever they went, Martha, who left the service to care for their three children, made her voice heard.

When they were stationed in Great Falls, Montana, in the 1960s, William, a master sergeant at the time, remembers his wife’s fight for a beauty parlor on base that could serve African-American women. At one point, he says, he was pulled aside and told to “control my wife.”

“In Montana, she was very involved in the community and fighting for people’s rights there, especially African-American rights,” says her daughter, Regina Wills, 56. “She has always been involved. If she hears someone needs help, she is there.”

•••

When the family moved to Tucson in 1969, they had worshiped mostly at African-American churches.

“We began to read the Word of God and learn some things that we were missing before that hadn’t been revealed to us,” Martha says. “We saw the need to get out there and look at the bigger picture and not stay in our comfort zone.”

The nudge into discomfort took the family to mostly white congregations.

That divide started to bother their son, who eventually pastored Sunshine Training Center, which he started in the 1980s.

“He saw, OK, there’s the black church over there, the white church over there, the Hispanic church over there, and he would be concerned why they didn’t know each other and why they didn’t get together,” Martha says.

In the early days of Sunshine Training Center, the congregation of about 50 often ditched service on their campus at 2145 S. Sahuaro Ave., to attend services elsewhere.

Others did not share their enthusiasm or see a need for such a ministry. Martha recalls pushback from other Tucson religious leaders, who she says have slowly come around.

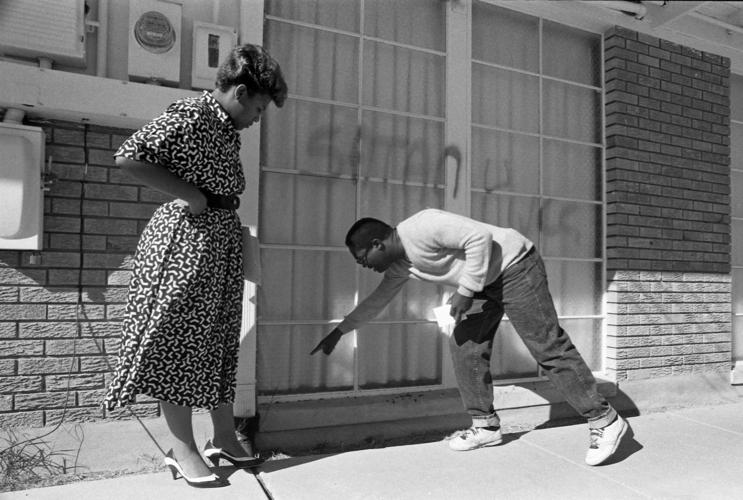

The Willses also encountered opposition directed at their church campus — obscenities yelled when they moved into the building in 1987, feces smeared on door knobs, windows smashed and vulgar graffiti scrawled on the building, William says.

“We went through this in Tucson, Arizona,” Martha says. “We want to break down these barriers that cause us to be separated, and that’s why we’re doing what we’re doing.”

Before his death, their son started programs through his ministry directed at prisons, nursing homes, literacy and youth, among others.

He also served as secretary for the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance in Tucson and as a board member for organizations such as the Tucson Ministry Alliance.

“I want to see change,” Martha says. “I believe that our son was the catalyst to change.”

•••

Martha remembers a conversation she had with her son several weeks before his death.

“He said, ‘Mom, I believe I’m getting ready for another phase of ministry,’ ” Martha recalls. Then, he told her to keep going. “And I’m thinking, ‘Why is he saying that?’ ”

On May 26, 2013, William and Martha found their son after he collapsed in his bathroom. The cause of death is unknown, though he had called his parents earlier that day to ask for a ride to the emergency room. He said only that he didn’t feel well. He was 58.

“That was a sad day, really sad,” Martha says. “But I realized work had to be done.”

With the conference already planned that year, the family carried on without their “catalyst.”

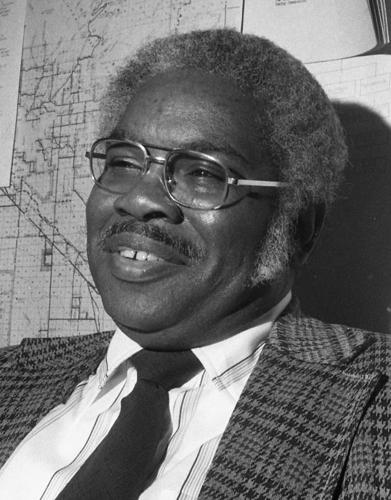

“They are a family if there ever was a family,” says the Rev. Otis Brown Jr. of Siloam Freewill Church and president of the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance. “They don’t have a huge church, but they make an impact on the church world and the public world.”

Everyone stepped in to help, with Martha taking on the role of coordinator and leader for both the conference and the church. They work with a variety of Tucson churches and ministries, such as 4Tucson. Donations fund the conference. The family anticipates this year costing less than $20,000, though the cost has ballooned in past years, depending on speakers and performers.

“From sunup to sunset they go from one place to another reaching out to people, letting them know about the racial reconciliation conference,” says Sheree Carradine, who has known the Willses since the late ’80s and wrote about them in her self-published Sarah Magazine. “They just go nonstop. … If they are not on the phone, they are out in the community reaching out to people.”

For several years now, Vice Mayor Richard Fimbres has supported the conference by presenting conference honorees with medallions and certificates of appreciation.

“God has really blessed them with a lot of energy,” he says. “They have gone through a lot of tragedy and are resilient and have been able to bounce back from the challenges the good Lord has given.”

•••

Ultimately, the family strives to bring people together.

Each fall, they put on a festival, which started as a safe place for their granddaughter on Halloween. Almost 30 years later, it draws roughly 1,000 people, William says.

They also hope to build a fine arts community center on their church campus.

In all of it, they want to cultivate relationships that celebrate diversity.

Mary Belle McCorkle, a former member of the Governing Board for Tucson Unified School District, met the Willses as a principal at their children’s school. Martha pressed McCorkle to attend the conference. When she did, she loved it.

“It was a reconciliation not only of races, but it was also like a reconciliation with God,” McCorkle says.

For Martha, it comes back to a prayer of Jesus Christ’s for unity among his followers.

“If he wants us to be one, why can’t we?” Martha says. “Why can’t we understand? Why can’t we go ahead and be with our brothers and sisters?”

The three-day conference, with its multicultural fine-arts show and outside speakers, explores cultural differences because the Willses believe misunderstanding often causes conflict.

“We are part of a church that is universal but not uniform,” says the opening speaker at the conference, the Rev. Elwood McDowell of Trinity Missionary Baptist Church.

Having unity also means having frank conversations about uncomfortable topics and long-held prejudices. The Willses are not naive. Instead, they choose not to accept hostility as the status quo.

“It is time,” William said. “When you think about it, throughout the nation now, they’re talking about doing things like this. It’s not just here in Tucson.”

In past years, Regina Wills has seen an increase in the diversity of conference attendees. They hope the trend will continue.

“Out of all of this, I hope people understand that we need to come together, and we need to understand each other,” Martha says. “Be sensitive. Be aware. You’re different than me, but you’re somebody, so we need to work together.”