When Jullisa Sanchez answers the front desk phone at Tucson’s Ronald McDonald House, she might as well be speaking to someone in her family.

Sanchez, a 21-year-old public health student at the University of Arizona, knows from experience how the facility can help a family.

She has stayed here.

The families who spend the night at the Ronald McDonald House must live at least 30 miles away from its location at 3838 N. Campbell Ave., Building 6, and be in town so their child under the age of 21 can receive medical care in the Tucson area, says Anne Rounds, the chief development officer of Ronald McDonald House Charities of Southern Arizona. Donations are accepted, but families can stay at no cost.

The house has 28 bedrooms, a kitchen, a backyard and common areas. It’s a place to call home when so much is in turmoil.

Sanchez is one of about 110 volunteers the nonprofit has spent the week honoring as part of National Volunteer Week. They cook, they drive, they clean. They do the little things.

“They’re everything,” says Rounds, one of seven paid staff. “Really they are the foundation for which we are able to do what we do. As staff, we have administration and oversight, but they are the smile, the human connection, the emotional support.”

Here are just a few of the volunteers that make this place run.

Jullisa Sanchez, 21

Sanchez decided to volunteer after her newborn sister stayed in the hospital from December 2013 to May 2014 following an emergency cesarean section.

Sanchez’s sister Jewelianna was born more than two months premature and required two surgeries at Banner — University Medical Center Tucson. Although Sanchez was a freshman at the University of Arizona with a Tucson apartment, her family is from Nogales, Arizona. She had a roommate, and her apartment had stairs, so her mother couldn’t stay with her.

Instead, her mom spent five months at the Ronald McDonald House.

“It goes beyond having a place to eat and rest and all of those things,” Sanchez says. “It was like having a support system in Tucson.”

Sanchez remembers the relief of having basic details attended. Even a free haircut given by a volunteer brought joy.

“Volunteers made a difference in the whole stay, and I really wanted to give back when this was done,” she says.

“I decided when this was all over, I wanted to comfort people the way they did and help out.”

In August 2014, Sanchez started spending a few hours each week answering phone calls, tidying the kitchen and even translating for Spanish-speakers.

“When I’m here, I know how big of a difference I’m making in people’s lives, and I know that they are going through a really hard time,” she says. “Any little thing helps.”

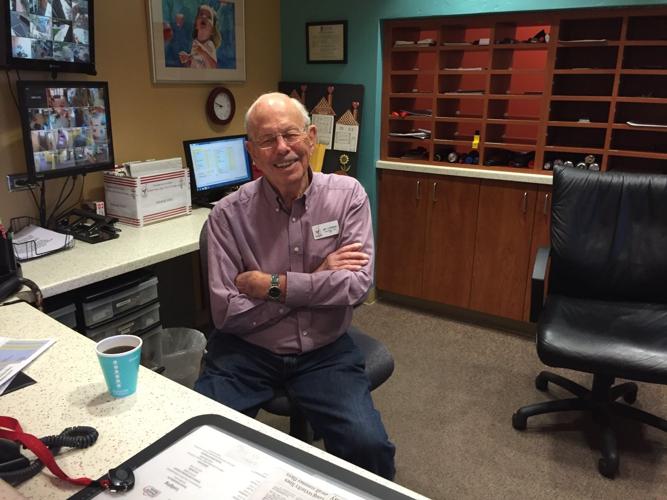

Dr. Arthur N. Lindberg, 92

At the Ronald McDonald House, Lindberg has found healing of his own.

For about six years, he has manned the front desk for three hours every Friday.

When guests enter, he sees the whole family, just as he did during his career as a family practitioner in Glendale.

“It’s just a worthwhile job,” the retired doctor says of his volunteering.

His son, one of his four children, suggested he volunteer after Lindberg lost his third wife to health complications — this time to a surgical procedure for pancreatic cancer.

Volunteering gave him something to do in the midst of a “depressed phase.”

“Medicine is just helping people,” he says.

Eleanor Furtak, 77

When Furtak retired from Prudential Real Estate in 2001, she knew she needed to volunteer.

A friend suggested she check out the Ronald McDonald House, “and that’s the beginning of the love story,” Furtak says.

Instead of working at the main house, Furtak has spent the last 14 years in the Ronald McDonald Family Room at Banner Children’s — Diamond Children’s Medical Center.

She makes the coffee and welcomes pediatric inpatient families. She grieves with them and cheers with them — over medical victories and when her beloved Wildcats win.

She knows how these parents feel. She lost her own son Greg years ago.

“You never get over it, but it does get better,” she says. “You come to feel like you’re going to live.”

The families stick with her — from children with cancer who visit years later as college grads to the mother she brought snacks and coffee to in the pediatric intensive care unit. When that mother’s 3- or 4-year-old daughter died, Furtak stayed in touch.

Yellow butterflies remind that mom of her daughter, and so Furtak shares each time she spots one.

“This has added something to my life,” Furtak says. “It has made me realize that we can do something. …

“Even though there is so much to be done when you see children and families and sickness, that one person can do something, you have to be happy with that.”