The attorney ambles slowly into the courtroom.

His hair is perfectly brushed. There’s a fresh shine on his shoes and not a single wrinkle on his impeccable suit.

Other than a stiff-legged gait, nothing belies his age. Every aspect of his countenance says professional.

Tucson defense attorney Brick Pomeroy Storts turns 80 years old this month. He may be the oldest practicing criminal defense attorney in town, but shows no signs of slowing down.

Storts keeps a full caseload, managing clients accused of crimes that range from drug offenses to murder.

He can’t say with certainty how many cases he’s brought to trial nor how many clients he’s defended. But both number in the thousands.

As his 80th year approaches, Storts has started to reflect on his life, career and possible retirement after more than 50 years in the legal profession.

STORYTELLER STYLE

“He’s the hardest worker you can imagine,” said Rick Unklesbay, a longtime deputy Pima County prosecutor who has tried many cases against Storts. “He’s going to outwork you and present the best case he can.”

Unklesbay said Storts has a courtroom manner that speaks to the different era.

“You see a lot of people today with a different style, it’s really not all that personable,” he said.

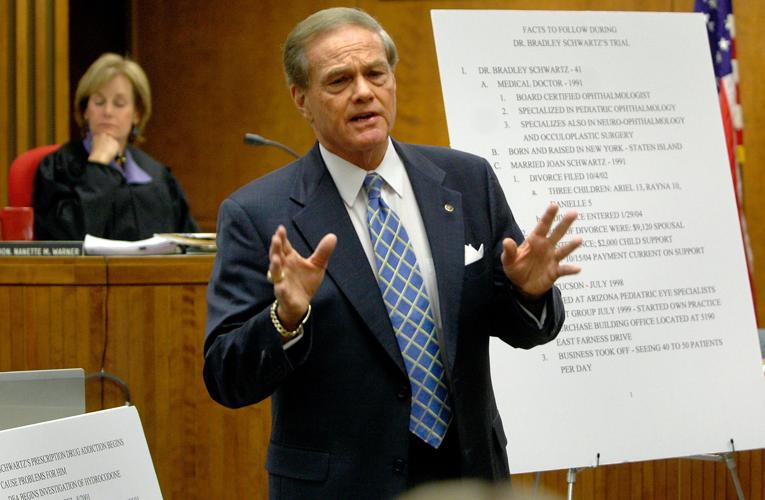

Storts, however, is known for a down home, storytelling style in court. Along with that, Storts also is known for giant storyboards he brings to trial.

“He’s pretty infamous for that,” Unklesbay said.

Storts said he likes to use the boards as an outline to his cases, making it easier for jurors to follow along during opening statements and closing arguments. Plus Storts says he’s convinced — despite all the science and expert witnesses that bombard jurors today — cases are won, and lost, in opening statements.

“If you don’t lay out your case in the opening statements, you’re not going to salvage it in closing arguments,” Storts said.

Pima County Superior Court Judge Richard Fields said telling stories is just part of Storts’ character.

“He’s always telling stories,” Fields said. “He uses that very effectively in the courtroom.”

SECOND CHANCES

Defense attorneys always fight for second chances for their clients, but Storts seems to take this role to heart.

“I think if he didn’t show up to the jail on a Saturday the guys that work there would call for search and rescue,” Fields said.

Unklesbay, too, said he often sees Storts returning from client visits at the jail on Saturdays. The two live on the same street and have become friends over the years.

“On a Saturday he’ll drive by on his way from the jail, always in a suit and tie,” Unklesbay said.

Storts said big cases where defendants face decades or even life in prison can’t be measured in simple win or lose terms.

“Most of your wins generally are not home runs,” he said.

Rather, it’s a matter of trimming some time off of a sentence.

“There’s a hell of a difference from doing 11 years or doing five years,” Storts said.

Storts said he feels an obligation to his clients because he understands more than most attorneys what it’s like to lose almost everything.

A YEAR IN JAIL

“I did 365 days in Pima County jail on work release,” he said. “I know what it’s like when that electric door closes.”

Storts was disbarred in 1990 for misappropriating a client’s funds. He pleaded guilty to two felony charges as a result.

It was a trying time for Storts, which he said was made worse by a drug habit.

He worked for more than six years as a paralegal and legal researcher while paying thousands of dollars in restitution. The Arizona Bar Association reinstated him in 1996.

Storts immediately picked up a first-degree murder case involving a man who killed a 15-year old boy in a drive-by shooting.

“I just never have looked back,” Storts said.

He’s also extended second chances to others. Among the most notable was Ken Peasley, the former county prosecutor who was disbarred in 2004 for eliciting false testimony from a police detective in a high-profile first-degree murder case.

After the late prosecutor left the county attorney’s office, where Peasley had been one of the most feared and revered prosecutors, Storts hired him to work as a paralegal.

“I feel that Ken was one of the brightest lawyers I ever worked with, he was brilliant,” Storts said.

DOCTOR’S SON

Storts was born here in 1936, at St. Mary’s Hospital.

His father, also named Brick Pomeroy Storts, a well known pediatrician who moved here from Missouri with his wife, Gladys.

Storts said his dad initially was hired as a doctor for the mines in Ajo. But rural living west of Tucson was not what Gladys Storts had in mind.

“Gladys lasted about two weeks in Ajo,” he said.

The elder Storts eventually went into private practice in Tucson and settled into a midtown home. Storts still lives there today.

His father furnished his office with furniture given to him by Roscoe Kerr, who ran the Parker-Kerr Mortuary.

Storts jokes about what his father’s patients must have thought sitting in chairs with the name of a funeral home on it as they waited for their appointment.

After high school, Storts went to the University of Arizona where he played football for legendary coach Warren B. Woodson.

He left after a few years when Woodson left and Ed Doherty took over.

“I wasn’t going to able to play,” Storts said, adding he wasn’t on an athletic scholarship.

He finished his football career at Missouri Valley College, where he and the 1958-59 team played in the Tangerine Bowl in Orlando, Florida.

After graduating with a degree in economics in 1959, Storts decided to stay in Missouri and attend law school, though he had few illusions about ever practicing law.

He didn’t even have to pass an exam to get into law school.

“The idea was to flunk out 60 to 70 percent of the freshman class,” he said.

Much to his surprise, Storts didn’t flunk.

That started a career as a prosecutor in St. Louis County, Missouri and he later worked for the Missouri Attorney General’s office.

By 1976, Storts returned to Tucson and started his defense practice.

RETIREMENT TALK

With his 80th birthday just days away, Storts said it might be time to consider retirement.

Back pain has slowed him in recent years, making walking difficult sometimes. It has also hampered his ability to hunt, which he enjoys on the rare occasion when he takes time off.

Fields said he can’t imagine Storts retiring because his work plays such a big part in his life.

“He needs it, it’s almost like his sustenance or the air he breathes,” Fields said.

Both men share a passion for hunting and have taken trips together, although Fields said Storts seems to have work on his mind even in his down time.

“Just about the time I’m beginning to feel like a mountain man again, he wants to go back to work,” Fields said.

Storts has put off back surgery for fear it could cause more problems than it fixes and, he says, it would cause him to miss months of work.

And he also worries maybe he’s not as sharp as he once was.

“I worry about, do I remember everything,” he said. “My wife laughs; she says I have a better memory than 999 other people.”

Storts and wife Michelle “Mickey” Wilder have been married since 1992.

He has two children from a previous marriage and one adopted child from a short-lived marriage while in college.

Storts has eight grand children.

Even as he ponders his age and possible retirement, Storts hasn’t slowed his pace.

As soon as next month he’s set to start a death penalty trial, involving a woman accused of killing her 4-year-old son

He knows the case will be a grueling and emotional endeavor that could last more than a month.

He’s determined to bring his A-game, for his client and for himself.

“You don’t want to doing something when everybody else says, ‘why didn’t he quit when he was on top,’ ” Storts said.