PHOENIX — The way Lisa James sees it, Proposition 207 is not about whether people should be able to use marijuana.

She said if Arizonans want to use marijuana legally there’s a simple solution: Repeal the laws that now make its sale and use illegal.

But James, who chairs Arizonans for Health and Public Safety that opposes the measure, said that’s not what’s on the Nov. 3 ballot.

“If they wanted to do that, they could do that in a page and a half,” she said.

Instead, James said, Prop. 207 is a complex set of regulations on 17 pages that is financed by for-profit organizations that will benefit if voters approve.

Chad Campbell, chairman of Smart and Safe Arizona, the industry-financed campaign that crafted and is backing the measure, does not dispute there’s a lot of detail on all those pages beyond making it legal to possess up to an ounce of marijuana and up to six plants. But he said that is necessary to ensure the drug is properly controlled, that there are limits on how it can be marketed and, potentially more significant, that it generates the estimated $300 million a year that would be earmarked for education.

What’s not necessary, said James, are some other provisions tucked into the measure.

For example, it allows the new recreational marijuana shops, created if the measure passes, to share premises with existing medical marijuana facilities.

James said it changes the laws for medical marijuana dispensaries, such as removing the existing requirement that medical marijuana dispensaries be operated as not-for-profit entities, one of the selling points behind the 2010 measure that legalized marijuana for certain medical conditions. And it also eliminates the requirement that these facilities have a medical director.

Campbell dismissed those concerns as irrelevant.

He said even if medical marijuana now would be sold by those seeking a profit, that wouldn’t necessarily boost the cost.

A brief guide to state absentee voting rules and resources for requesting mail-in ballots for the upcoming election.

“It will be market driven,” Campbell said. And he said medical directors are unnecessary because the initiative includes requirements for testing as well as limits on the strength of edible marijuana products, though there is no cap on the concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol — the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana — that can be in the leaves and flowers that are sold.

As much as James says the 17-page initiative is too chock full of provisions versus simple decriminalization, there also are more restrictions that she actually wants in the measure.

Advertising and promotion

The measure would not only prohibit sales to those younger than 21 but also ban the sale of products that resemble humans, animals, fruits, toys or cartoons. And it specifically bans marketing marijuana products to children.

James said that’s not enough. She wants to block promotion of marijuana in ways that children can see.

“They could have restricted their access on social media, for instance,” she said, saying youngsters are spending a lot of time on the internet.

She conceded there is no such ban on promoting alcohol or tobacco. But James said that is irrelevant.

“I can see a lot of things on the internet,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean I want to see more of them.”

There’s also the issue of driving while drugged.

The initiative spells out that it remains illegal to operate a motor vehicle, boat or aircraft “while impaired to even the slightest degree.”

Only thing is, there is currently no technology, similar to a breath test, to determine the level of THC in someone’s blood. And even if such a device becomes available, there is no standard in the initiative to say that a specific THC level is a presumption of driving impaired, the way someone with a blood-alcohol level is presumed to be driving drunk.

Prop. 207’s limits, guarantees

Then there’s the issue of how Prop. 207 is structured.

Put simply, it limits the number of recreational marijuana facilities that can be set up. Campbell said Arizonans don’t want a situation like Denver where recreational outlets have popped up all over the city.

But there’s something else: It pretty much guarantees that the operators of existing medical marijuana dispensaries will get one of the new licenses.

“This is about big marijuana money and a whole commercial industry,” James said.

That provision, in turn, helps explain why virtually all of the $3.5 million collected to hire the paid circulators to put the issue on the ballot and finance the campaign came from companies that already have marijuana facilities in the state. And that was as of the most recent report available in July.

If the state simply decriminalized marijuana possession and use, those exclusive licenses to sell the product would be worthless. But Campbell said it makes sense to have some controls and make it safe.

For example, he said, there are product standards and testing. And there even are some restrictions on how it can be marketed to ensure that ads are not targeting those younger than 21 for whom the drug would remain off-limits.

“The entire point of this is to create a safe regulatory environment for the use of this product in a responsible manner,” Campbell said.

He compared it to how the state regulates the sale of alcohol.

There is a bit of a parallel there. Aside from age restrictions, Arizona limits the number of licenses for bars.

But there are no limits on how many restaurants can serve alcoholic beverages. And more to the point when talking about purchasing something to go, there are no caps on the number of grocery and convenience stores that can sell alcoholic beverages.

“Voters don’t want it to be unlimited,” Campbell said of retail marijuana outlets.

New licenses

He did not dispute that the operators of the existing 130 medical marijuana dispensaries would get first crack at the licenses for recreational sale of marijuana.

But Campbell pointed out there also is a requirement to give out 26 new licenses under a “social equity” program to help those who are from communities “disproportionately impacted by the enforcement of previous marijuana laws.” And there are provisions for added dispensaries as population grows.

The initiative does have some options for local control.

On paper, it allows cities — and counties in unincorporated areas — to limit the number of retail outlets and marijuana testing facilities, regulate their hours of operation and outright prohibit both.

But there are some caveats that go with all that.

Restrictions on recreational facilities cannot be more restrictive than those imposed on medical dispensaries. And, more significantly, it says there cannot be new restrictions on recreational marijuana outlets if they are operated at the same location as an existing medical marijuana outlet, something that again gives an advantage to those already on the ground.

Prospective legalization of marijuana use is only one part of the measure. It also sets up a procedure for anyone who has previously been convicted of drug possession to have the criminal record wiped out.

The arguments by foes that this isn’t a simple repeal of laws making it a crime to possess marijuana still leaves the fact that it is the only proposal on the November ballot to allow adults to use the drug for recreational purposes. And despite her complaints about the complexity of the issue, James sidestepped the question of whether she and others who oppose this measure would support simple decriminalization.

“I think that you would see differences of opinion,” she said.

“There are some people who are fine with decriminalization,” James said. “But Prop. 207 is not the way to do it.”

Photos: First medical marijuana dispensary in Arizona

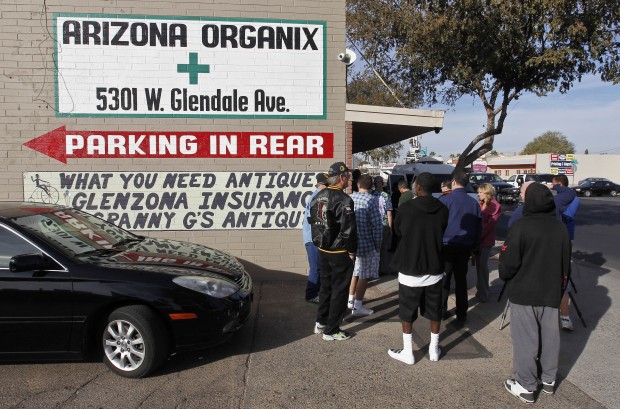

Arizona Organix, the first legal medical marijuana dispensary to open in Arizona, began dispensing Thursday Dec. 6, 2012, in Glendale, Arizona. Dozens were waiting when the doors opened.

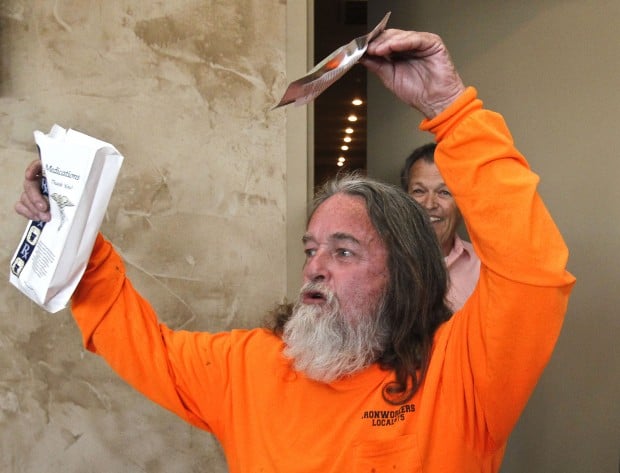

Dennis Cox shouts as he holds up his marijuana after making a purchase at Arizona Organix, the first legal medical marijuana dispensary to open in Arizona, Thursday Dec. 6, 2012, in Glendale, Ariz. Several dozen waited outside for the Glendale dispensary to open, the first among 96 applicants chosen through a lottery system for 126 geographic areas across the state.(AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)