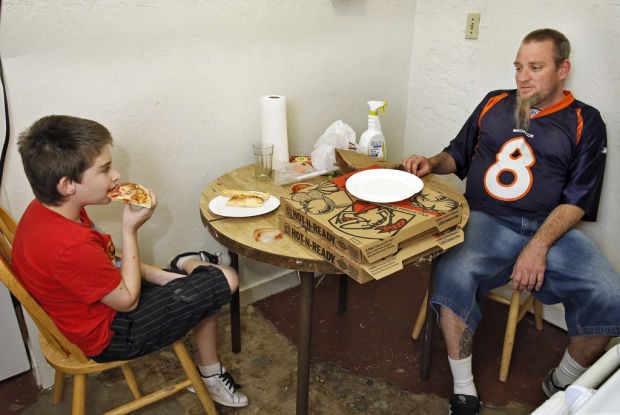

Pat Hatley wants to keep his small family together — but as a homeless dad, he worries every day that he might lose custody of his 10-year-old boy.

The single father and his son Trent can stay two more months at a Primavera Foundation shelter for families, but after that he doesn’t know what’s next.

He says he’s struggled to get benefits — including welfare and Section 8 housing — after years of heavy lifting ruined his back and limited his work options. He relies on odd jobs and food stamps to get by, but often that’s not enough.

“There are people not trying to abuse the system that just need help,” says Hatley, who has had sole custody of his son for seven years. His biggest fear is that, if he can’t find a more stable way of life, Child Protective Services will take Trent away.

More than 15,300 Arizona kids are in foster care — an all-time high — and the fraying safety net for poor families is a key reason for the spike, child welfare advocates say. Cuts to child-care subsidies, welfare, family support programs, and substance abuse and mental-health services have pushed more families to the edge, they say.

The state’s surge in foster care comes as other states see significant declines. Nationally, the number of children in out-of-home care fell 18 percent between 2007 and 2012. Forty-one states saw a decrease.

But in Arizona, which made deep cuts to services that help children and families, the number of kids in out-of-home care soared by 48 percent.

“The state Legislature is the real culprit here,” says Eric Schindler, president and CEO of Child and Family Resources in Tucson. “The choices they have made, the cuts they’ve made, have real-world consequences.”

The increase is putting enormous pressure on every part of the child-welfare system, from crowded dependency courts to overwhelmed CPS caseworkers to strained foster families.

Children are sleeping in CPS offices as caseworkers scramble to find a foster or group home placement. Some kids are placed hours away from their families, friends, schools and all that’s familiar.

“I’ve been in this business 35 years, and I’ve never seen it this bad,” says Susie Huhn, executive director of Casa de los Niños, which provides child-abuse prevention and intervention and runs an emergency shelter for kids.

Neglect allegations are driving an increase in CPS hotline reports, as fewer parents qualify for aid or get help for their addictions and mental-health issues. From 2009 to 2013, reports of neglect jumped by more than 50 percent in Arizona, while abuse reports remained stable. Neglect comprised about 70 percent of CPS reports assigned for investigation last year.

As more Arizona kids are taken from their homes, fewer families are stepping up to foster them. Since reimbursement rates to foster families were cut in 2009, the number of foster homes leaving the system has almost always outpaced the number of new homes licensed. That means more children placed in less personal — and more expensive — congregate care settings, like group homes and emergency shelters.

CPS caseworkers are caught in the middle, juggling impossibly high caseloads that give them less time and fewer resources for each family they’re trying to help. The agency’s 28 percent turnover rate exacerbates the crisis, says Dana Wolfe Naimark, president and CEO of Children’s Action Alliance, a Phoenix nonprofit that advocates for children.

“They’re new, not seasoned, and have caseloads far too big. The expectations of them are pretty unrealistic, and things fall through the cracks,” she says.

That includes the agency’s failure to investigate more than 6,500 reports of abuse and neglect over the past four years, a lapse Gov. Jan Brewer last week called “unconscionable.”

Five CPS supervisors were put on leave and child-welfare advocates are calling for the resignation of Clarence Carter, director for the Department of Economic Security, which oversees CPS. Last week Brewer named an independent team to determine what happened and ensure all the missed cases are investigated.

CPS faced a huge backlog even before these cases were discovered. Of the nearly 21,000 cases assigned for investigation in the second half of 2012, about 3,600 were still open in September 2013, says the Children’s Action Alliance. About 10,000 current CPS cases are “inactive,” meaning there has been no follow-up for at least two months.

Unmanageable caseloads can prove deadly to children. The number of kids who died of maltreatment in Arizona while they were the subject of a CPS investigation more than doubled between 2007 and 2011, from six to 15. It fell to 11 in 2012. Last year, 33 children died as a result of maltreatment after previous CPS involvement, compared to 26 in 2007.

Child-welfare caseworkers don’t have to be overworked and underpaid, but the DES has accepted that as status quo, says Tim Schmaltz, CEO of the nonprofit Protecting Arizona’s Family Coalition in Phoenix.

“If you don’t have manageable caseloads and you don’t have community resources, you make it an impossible job,” says Schmaltz, a former CPS caseworker. “We would never think about cutting first responders, like firefighters and police officers.” But he says when it comes to child welfare “we don’t hesitate.”

SAFETY-NET PROGRAMS CUT

Arizona, facing severe budget shortfalls during the recession, slashed safety-net programs that help poor families get by.

In 2009, DES froze enrollment in the Child Care Subsidy Program, which helps the working poor pay for day care. Sixty-nine percent fewer children got the subsidies in 2012. More than 6,300 kids are on the waiting list.

“That family is either forced into a position of not working to stay home and take care of the kids, or working and neglecting their children,” says state Rep. Kate Brophy McGee, R-Phoenix, co-chair of the CPS Oversight Committee.

Last year, legislators restored $9 million for child-care subsidies, but the money will go first to families already in the child welfare system, leaving little, if any, for those struggling to stay together.

“Child-care subsidies are a huge safety net for the working poor,” says Annabel Ratley, former division director for children and family services at the Easter Seals Blake Foundation. “Instead, it goes to the kids who are removed. And then when kids are returned to their families, it stops. There’s something backwards about that.”

Limits on cash assistance —or welfare — benefits have meant less support for Arizona’s most vulnerable families.

State funding for family preservation services — in-home programs to boost parenting skills and strengthen relationships — was halved from $43 million in 2008 to $22 million in 2012, Children’s Action Alliance says.

“Not only is the child-welfare system not functioning at the same level it was, but the community-support services that are often the eyes and ears of the child-welfare system were cut,” says Linda Spears, vice president for policy and public affairs for the Child Welfare League of America in Washington, D.C.

Cuts to safety-net and in-home services put the state on an inevitable path to more children in foster care, says Patti Caldwell, executive director of Our Family, which has the region’s only teen-crisis shelter.

“I don’t know how you’d have any result except for the one that we’re seeing right now,” she says.

Educators see the increasing desperation daily in the form of more hungry or abandoned students. In the Tucson Unified School District, the number of unaccompanied minors — children without legal guardians, in temporary living situations — reached 176 last year. That’s triple the number two years earlier.

And it doesn’t include kids in the child welfare system. Many “couch surf” or stay with relatives or friends, says Dani Tarry, the district’s director of family and community outreach.

Some chronically absent students are actually at home caring for siblings so their parents can work, says Jim Brunenkant, principal at Flowing Wells High School.

For children over 16, repeated absences must be reported to CPS or law enforcement. Educators also must report students who say they haven’t eaten since school lunch the day before.

“Nothing breaks my heart more than a parent who’s doing everything they can for their child and they just fall short,” Brunenkant says. “They’re barely scraping by and feeding their kids as best they can, but it’s not good enough, unfortunately. So you have to report it.”

Jim Hillyard, deputy director of operations at the DES, says it’s speculative to draw a direct correlation between safety-net cuts and the increase of kids in foster care. He says media coverage of child welfare has intensified since the 2011 death of 10-year-old Ame Deal of Phoenix, who died after her adult cousins locked her in a small box as punishment.

“The media has really become focused on child welfare, and has continued to make it a present issue with the public,” he says. That’s a good thing, he says, because valid reports to the CPS

hotline are up.

Critics say the DES was too slow to ask the Legislature to restore cuts made during the recession. But Hillyard says funding requests are made 18 months in advance of each fiscal year, and DES did not anticipate the growth in reports that started in 2011. Statewide, CPS hotline reports surged 26 percent from 17,500 during a six-month period in 2011 to 22,100 reports during the most recent six-month period, ending in March.

“That’s unprecedented in the history of the CPS system,” Hillyard says. “No one had a crystal ball.”

MENTAL-HEALTH FUNDING

Mental-health care and substance abuse treatment fell out of reach for many of the state’s poor in 2011, when Arizona froze enrollment for childless adults in the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, the state’s Medicaid program.

Parents who lose custody of their children are considered childless adults in AHCCCS, adding more barriers to their recovery and reunification with their children, says Cindy Greer, chief of clinical services for the Community Partnership of Southern Arizona, the public behavioral health authority for Pima County.

The Community Partnership, which provides services for children and parents involved with CPS, gets federal funds for parents with a primary diagnosis of substance abuse, but Greer says the money doesn’t cover mental-health treatments, which can play a decisive role in recovery.

State funding for uninsured adults with a diagnosis of “serious mental illness” was cut from $16 million to less than $6 million between 2010 and 2011. The funds were restored last year.

Many are holding their breath until January: Arizona was one of 26 states that opted to expand Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, so next year AHCCCS will cover all adults earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

Families also lose DES-funded behavioral-health services after they get their kids back, causing delays when they reapply for coverage.

“A lot of support stops when kids are returned,” says Ratley, of the Blake Foundation. “That doesn’t make sense. The time of return and reunification should be the time when you are continuing to support that family.”

Recovering meth addict Shannon Brown says more support from CPS and better behavioral-health care would have helped her reunify sooner with her kids.

A single mom, Brown began using meth with an abusive boyfriend in 2004 while teaching high school and raising three children. For a while, the drug made her energetic and efficient, she says. But eventually she was using more and more, and someone reported her to CPS. Her children were put in foster care in 2007.

It took her more than a year to get sober and, for most of that time, her underlying depression went untreated. Demands from CPS seemed overwhelming, especially since she was uninsured, without a phone or car. At the same time, she was trying to avoid the drug that had been her coping mechanism for years. She says she struggled to stay off meth while trying to get to dozens of CPS-mandated appointments by bus. “I’m a fairly intelligent person and I was still completely lost,” she says.

Once her depression was diagnosed and she was put on anti-depressants, she was able to get sober. Now clean for five years, Brown has her kids back and is a family-support partner at the Blake Foundation, working with parents in CPS who are dealing with substance abuse.

“I want parents out there to hear that it’s possible,” she says. “They need to hear success stories, that CPS will give you your kids back.”

HARD LINE CAN BACKFIRE

A series of child fatalities in 2010 and 2011 — many perpetrated by parents with prior CPS involvement — prompted the creation of a governor’s task force on child welfare and reforms to the state’s child welfare agency.

Reforms are common after child deaths, and increased scrutiny of the agency often leads to more removals. That can protect children, but it also can break up families who could have remained intact with support.

CPS investigators “have got to decide sometimes in a matter of hours to remove that child or not,” says former state Rep. Pete Hershberger, a Republican who supported CPS reform 10 years ago. “If they make a mistake and leave the child there and something happens, their name is going to be on the front (page) of the paper.”

In Arizona, the focus on preventing fatalities, without more funds for preventive services, meant a surge of new families in the system, says Schindler, of Child and Family Resources.

A similar scenario played out in 2003 after a series of child maltreatment deaths involving families already involved with CPS. Then-Gov. Janet Napolitano pushed through extra funding for CPS, as well as legislation mandating that all cases get investigated. The reforms also dismantled the state’s “differential response” program, a kind of triage system that refers low-risk families to voluntary support programs instead of a CPS investigation and dependency court.

Actually, many foster children would be better off staying in a less-than-ideal home if the family could get some support, says Christa Drake, executive director of In My Shoes, a program that advocates for children aging out of foster care.

But when parental rights are severed prematurely, children can spend years in the system. Too many never find a “forever home.”

“I see so many youth who just don’t need to be in care,” Drake says. And worse, “They’re not faring any better in foster care than they would have at home.”

TURNING THE SHIP AROUND

The booming foster-care population is not only bad for kids, it’s hard on the state budget. In-home visitation for an at-risk family costs $5,000 to $6,000 a year, compared with up to $30,000 a year for a child in foster care, says Huhn, of Casa de los Niños.

DES leaders say they can reduce the flow of children into foster care by returning to a differential-response system that offers low-risk parents support services instead of a CPS investigation. At least 18 states have such programs.

“What you don’t want is for a kid to come into foster care in a situation where they have well-meaning, hardworking parents who just lack resources,” says Kevin Keegan, president and CEO of Catholic Charities in Baltimore, and a former child-welfare official.

Maryland has ramped up efforts to keep families intact in recent years, and officials say they have paid off: The state’s foster care population fell 42 percent from 2007 to 2012.

Arizona also has bolstered its strained CPS system since the recession cuts. The DES spent an additional $46 million on child welfare last fiscal year and received another $58 million this year. The state also approved 200 additional caseworker positions.

Hillyard, of the DES, says that over the next two years, an expected increase in CPS workers will reduce caseloads enough that workers will have time to move 1,700 more kids out of the system.

The department also wants nearly $66 million for fiscal 2015 to fund 444 more child-welfare workers, including 50 in the Office of Child Welfare Investigations.

Arizona has neglected its children for so long that changing course won’t be easy, Huhn says.

“We made choices of cutting on the backs of our vulnerable families,” she says, “and we took so long to start to reinvest .”

The pace is still slower than many would like. Legislators got $5 million into the current budget for intensive family services, and have repeatedly asked the DES and the governor’s office how that money is being used.

They haven’t gotten an answer, says Sen. David Bradley, D-Tucson, who worked in child welfare for two decades.

In an email last week, DES spokeswoman Nicole Moon said the funds are committed to keeping children in their homes, but Bradley wants details.

“We realize CPS’ dilemma is always fighting the fire,” Bradley says. “But we wanted to get this money on the front end. Without it happening, there’s no end in sight here.”