As it gets tougher to climb the border fence or cross the desert undetected, more migrants are seeking asylum at legal ports of entry and creating a new challenge for border enforcement.

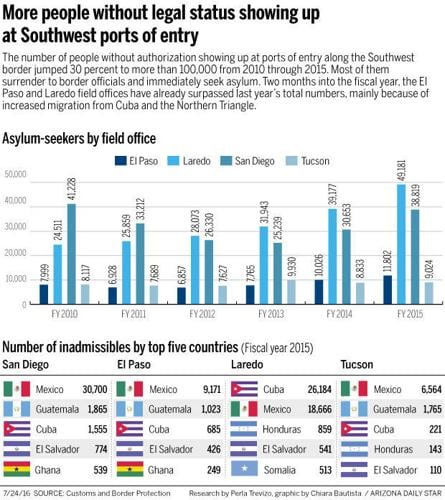

Since 2010, “inadmissibles” — Customs and Border Protection’s name for people who are caught at ports of entry without legal status, or those who are barred from entering the United States because they have a criminal history or are considered a terrorism threat — have risen 30 percent in the four field officers along the Southwest border: San Diego, Tucson, El Paso and Laredo, data obtained by the Arizona Daily Star show.

Most of this growth stems from increasing traffic through Laredo, which now has the highest number and share of people coming through. Nearly 50,000 people have passed through the Texas port with two months left in the fiscal year, up from 24,500 in 2010.

In Tucson, the number of Guatemalans showing up at ports of entry surged from 28 in 2010 to 2,323 so far this year. But overall traffic at ports here has stayed fairly steady because of a decrease in the number of Mexicans crossing the border into Arizona.

Statement of fear

starts asylum process

Research by Perla Trevizo

As soon as people who turn themselves in at an official crossing point say they are afraid of returning to their home country, it sets in motion the asylum process, which can drag on for years.

“More and more on the Southwest border, the new challenge is mixed flows,” said Doris Meissner, former commissioner of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service and senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute. “The basic illegal immigration of young men or younger Mexicans who are purely coming for job function is basically behind us.”

Recent migration trends are dominated by Central American families and minors who have more complex reasons for coming to this country — fear of violence, gangs and other dangers, Meissner said.

Cubans are responsible for a large share of this growth. Since fiscal 2010, the number of Cubans presenting themselves at Southwest ports of entry has grown from 5,500 to nearly 34,000 as of June of this fiscal year.

Cubans seeking to flee their government come here to take advantage of the United States’ “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy, which allows them to stay once they reach the U.S. Many more are entering through Mexico than Miami, the traditional route, in part because of tighter enforcement on the coast.

The practice is so common that Cuban migrants have given it a new nickname: “dusty foots.”

As relations between both countries begin to thaw, many fear this policy will change.

Meisner said the increase in the number of Cubans might also impact flows from other countries.

“Cubans present themselves at ports of entry because they know they’ll be admitted,” she said.

As word gets out, she said, others likely will try to do the same thing in hopes of getting an immigration hearing.

Court “dysfunction”

While political and economic conditions push people out of their home countries, experts say that smugglers and even some immigration attorneys are quick to adapt to more successful migration routes.

“If you have families or unaccompanied minors, a really good smuggler is able to earn his money by creating less danger and less likelihood of harm. At the same time it’s less trouble for the smuggler because you just go through the port of entry and ask for asylum.”

People seeking asylum in the United States can file an application with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, where an asylum officer reviews their case.

If the case ends up in immigration court, asylum seekers can wait three to six years for their claims to be resolved due to increasing backlogs.

Immigration courts are “under-resourced and underfunded to the point of being dysfunctional,” said Dana Marks, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges.

A recent hiring push aims to bring on as many as 55 new immigration judges by Sept. 30, she said. But recruiting and training judges doesn’t happen overnight.

There are 276 immigration judges nationwide, she said, 20 of whom are primarily in management, which means they hear few cases. Last fiscal year the Department of Justice, which manages the immigration courts, hired 23 new judges, but 22 retired.

Nearly 500,000 cases are pending in the nation’s immigration courts.

New kind of migrant “not a One-year” trend

The shift to the ports of entry means border enforcement has to be looked at differently, said Meissner.

“What’s happening in Central America, a large share of this, is not a one-year phenomenon or surge,” she said. “It’s an enduring phenomenon and that presents a new challenge for border enforcement and a challenge that requires different kinds of resources and a different kind of response than simply building up enforcement personnel along the Southwest border.”

The number of Hondurans showing up at ports of entry, for instance, decreased temporarily in 2015 as Mexico stepped up enforcement efforts along its southern border. But so far this fiscal year it has rebounded to nearly 4,000 people, most crossing in the El Paso and Laredo field offices. In 2014, almost 4,700 Hondurans showed up at official crossings.

What’s needed is a robust hearing system and a timely adjudication system, which both must be properly staffed and expanded, said Meissner. That will help the United States be “effective and relevant in the challenges for border enforcement that we are facing now and likely to face in years ahead,” she said.