The University of Arizona and community partners created a public archive with stories of undocumented migrants who were incarcerated in Arizona.

“Detained: Voices from the Migrant Incarceration System” project is a collaboration between the UA, the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project, which provides free legal and social services to individuals in immigration detention in Arizona, and Salvavision, a Tucson-based non-profit that provides aid and support to migrants.

The online archive, which went live in February, contains interviews with a dozen former detainees of the detention centers in Florence and Eloy, as well as art and memorabilia. One goal of the project is to allow formerly incarcerated migrants to tell their stories in their own words.

“We all approach this knowing that none of us are the experts; the experts are the people who are telling their stories,” says Susan Briante, UA English professor who worked on the project and has authored work around immigration. “The focus is on making sure that they’re allowed to tell the stories how they want to tell them and that they’re telling the stories in a way that is safe for them.”

The Florence Project helped establish guidelines for the project to ensure nothing in the archives would cause any harm to the participants. Everyone who took part in the interviewing also did a session on trauma-informed interviewing techniques.

Many of the interviewees’ names in the project are pseudonyms to protect their privacy, as some of their immigration cases are ongoing, and some still have concerns for their safety from experiences that caused them to migrate in the first place.

All the people interviewed spent time in immigration detention while waiting for immigration proceedings. Some of them were detained for years.

“All of the people who we spoke to have experienced some really horrific traumas,” said Greer Millard, spokesperson for the Florence Project. “They have shared with us and trusted us with some of the worst things that they have experienced in their lives. And we wanted to make sure that this was a safe experience for them. And for many people, that meant taking measures to conceal their identities.”

The oral histories in the archive span different immigration experiences, Millard said.

One woman interviewed was a Canadian national who had been living undocumented in the United States. While her experience was difficult, she had advantages because she is white and speaks English fluently, says David Taylor, photographer and professor of art who worked on the project.

“Her experience in detention was, while difficult and in line with the difficulty that everyone in that circumstance experiences, still privileged,” said Taylor, who has been focusing on the borderlands for decades and whose work inspired the project. “She was able to navigate the system and, in fact, help other people navigate the system.”

An Iranian immigrant, identified in the series as Afshin, “who literally got profiled at every turn for being Iranian,” Taylor said. “He was fleeing persecution in Iran only to be profiled as a terrorist upon crossing the border.”

Taylor said that Afshin ultimately prevailed in his asylum case because he could demonstrate that he was persecuted in Iran.

Some interviewees talk about being in detention during the height of COVID, and others recount the child separation policy that made headlines during the Trump administration.

As their detention experiences varied, so did participants’ experiences after detention. Some were deported, and others were able to begin the asylum process in the U.S.

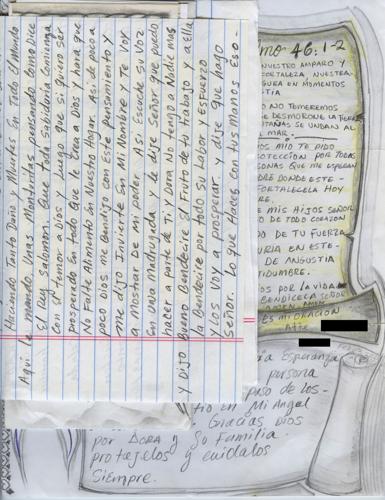

Besides the interviews, another component of the project is Salvavision Director Dora Rodriguez’s notebooks containing her correspondence with migrants in detention, many of whom she arranged bonds for or connected with sponsors.

Rodriguez has boxes and boxes of these notebooks, Taylor says, and he continues to make redactions of identifying information and put them into the archive.

“As archives operate, this is going to get bigger and bigger and bigger, and so the notion is that this becomes a destination for understanding the breadth, the human impact of this phenomenon of incarcerating people who are seeking refuge,” he said.

“Detained” was established with a nearly $60,000 Digital Borderlands Grant, part of a $750,000 grant the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation awarded to the University of Arizona Libraries for projects that “support the integration of library services into data-intensive, humanities-focused research on the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands.”

Other people who worked on the project include author and translator Francisco Cantú, School of Information graduate student Aems Emswiler, College of Law alumnus David Blanco, former UA associate professor and current Arizona State University faculty Anita Huizar Hernández and staff from the Florence Project.

The team hopes to continue adding more people’s experiences to the archive.

The archive launched with an event at the Blacklidge Community Collective that included stations where people could listen to interviews and digital projections of the art and memorabilia.

“Detained: Voices from the Migrant Incarceration System” can be found at detained.digitalscholarship.library.arizona.edu.

Another archive launch event will be held in Phoenix on May 4, from 7 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. on the ASU Tempe Campus in the Design North Building, Room 60. More event details, including information about parking and possible virtual attendance, will be available on the “Detained” website closer to the event.

“My goal in all of this is to ensure that people’s experiences do not disappear,” Taylor said. “These are people who don’t get to write history. They don’t usually have their say.”

The White House is reportedly considering once again detaining migrant families who cross the U.S.-Mexico border illegally.