Louis Cuen Taylor spent most of his life living in the structured environment of prison.

Every day for 42 years he was told when to wake up, what to wear, where to go and what to eat.

In his first year out of prison Taylor, now 60, has had a difficult time coping with the privileges and responsibilities that come with freedom.

Some of those who have supported him since his release are concerned for his future. But Taylor, himself, lives in the moment.

“I don’t like to plan ahead,” he said. “You can be here one day and gone the next. Life’s too fragile.”

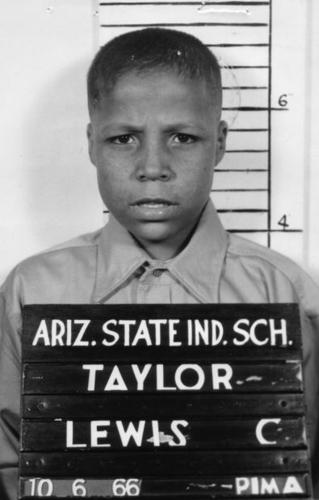

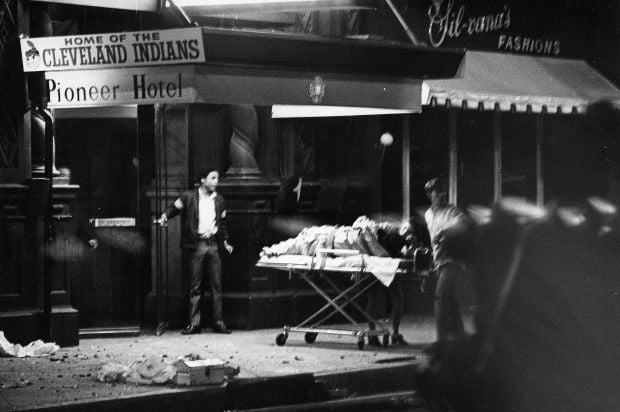

Taylor was a teen when he was sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of setting the 1970 Pioneer International Hotel fire in downtown Tucson that killed 29 guests. The Arizona Justice project secured his release in April 2013. (See box on Page C5)

As a boy, when he wasn’t serving time in juvenile detention for petty theft or running away from home, he was hustling on the streets — shining shoes, selling tamales, cadging cigarettes.

“The incident (fire) happened when he was 16. He went into prison when he was almost 18 and he was in there for 42 years. He grew up there, which is much different than someone who went to prison when he was 35 or 40,” said Andy Silverman an emeritus professor of law at the University of Arizona, who for years has been working with the Justice Project on Taylor’s case.

“When he got out and he had an apartment by himself. At first he felt very uncomfortable living by himself. He was a bit scared by it. As a kid he didn’t live by himself and for 42 years he didn’t live by himself,” Silverman said.

Taylor, who has no close family ties, never had the experiences common to most as they transition from teens to adults — interviewing for a first job, opening a bank account, paying rent, buying groceries. He never learned the responsibilities of being an adult.

“For a while he was losing those cellphones like they were pennies,” said Starr Sanders, who is married to Silverman, and has befriended Taylor.

For the first six months after his release, Taylor had a place to live, a job and lawyers who kept him busy with media interviews and speaking engagements. Since then he has been struggling with basic life skills — keeping a job, managing money, finding a place to live.

And he has stubbornly resisted taking advice from those people closest to him who try to help.

“I think one of Louis’ biggest problems, I don’t think he listens to anyone except Louis,” Sanders said. “He survived all those years in prison — whether it was good or bad or whatever. When you make a suggestion, he’s going to do what he’s going to do because that’s how he survived. If he did learn anything from anyone, it’s probably somebody he should not be getting advice from.”

Added Silverman: “In prison you don’t get advice from anybody. You get guards yelling at you, you get prisoners telling you stuff. At times, to be a survivor, you have to listen to your own instincts. For 42 years that’s obviously what he did.”

Sanders, a retired high school teacher, said Taylor reminds her “of an old adage that people, when they go into prison, whatever age they are when they go in, that’s where they stay because it’s hard to mature from that. He’s still locked into that period of time.”

Despite his struggles, Sanders said, “I think Louis has coped incredibly well. It’s a very tough world. He’s a very emotional person. I think the world of him. It’s been an unusual ride for a year — work, money, survival, who you trust. It’s been difficult for him.”

Another friend, Norma Feldman, agrees.

She met Taylor through her husband, retired Arizona Supreme Court Justice Stanley Feldman, who serves on the board of the Arizona Justice Project.

Taylor, she said, is “not doing as well as I would like for him to do. He has a good heart and he means well, but it just doesn’t work out for him. People take advantage of him because they know he’s a giver. They take from him and I think that’s hurtful for him.”

No matter the injury to his feelings, Taylor is guarded about his emotions.

It is a survival mechanism he learned in prison, Silverman said, where displaying emotions can be considered weakness.

“I ain’t doing bad. I just want to have peace. I don’t want to embrace everyone. Some people aren’t embraceable,” Taylor said.

Working in his favor, however, is Taylor’s ability to change with his circumstances. “He’s a chameleon to adapt to every situation — the son, the friend, the promoter — he plays different roles. I think it’s been hard for him,” Sanders said.

Taylor has lost money and belongings to people whom he befriended. At the end of April he began receiving state food assistance, but within a week he gave his card to someone who used up all the credit.

He’s also resisted finding regular work after he quit his job as a groundskeeper at The Loft Cinema.

HE received donations

Following his release from prison, Taylor received thousands of dollars in donations sent through the Arizona Justice Project. His attorneys used the money to buy him clothing and necessities. It also paid for a year’s worth of rent.

For the first six months after his release, Taylor lived in a townhome owned by the parents of Ben’s Bells founder Jeannette Maré. She manages the vacation rental for her parents and charged Taylor half the usual rental fee.

“I learned Louis was having trouble finding housing because of his arson conviction,” she said. “I called them (her parents) and asked about letting him live in it while he got acclimated. They were very compassionate. They really wanted to give him a chance and they were very, very open to it so they said, ‘Absolutely’.

“I think adjusting to life outside of prison is challenging — figuring out how things work, having a social life. It was a major, major transition for him,” Maré said.

When he moved in, Taylor didn’t even know how to lock the door to the townhome and had to practice using the key to engage the bolt.

Taylor was prevented from entering a transitional housing program after leaving prison because of his arson conviction.

“We tried hard to get him in,” Katie Puzauskas, director of the Arizona Justice Project, said in an email, “however, the program’s insurance company would not allow anyone to live there with an arson conviction. Because Louis was not fully exonerated, and the underlying arson conviction remained, the program would not take him.”

While living in the Maré townhome, Taylor found work as a groundskeeper at The Loft Cinema on East Speedway, but quit the job after six months.

“He took care of landscaping and cleaned up the parking lot,” said Peggy Johnson, executive director of The Loft. “It never looked better and hasn’t looked as good since. I think he enjoyed it because it was outside.”

Johnson was out of the country when Taylor quit his job and said she is not sure why he left.

Taylor said he took a lot of pride in the work he did at The Loft, but he was unable to make a connection with the other employees.

“That was a good job, but how long can you stay someplace where no one wants to bond with you,” he said.

Since then Taylor has worked sporadically — washing dishes at a restaurant and performing maintenance chores at a rental property — but nothing steady.

Occasionally he makes a few dollars selling what he calls “freedom photos” — pictures of him taken after his release from prison — but he has no real income and money donated to Taylor through the Justice Project ran out in less than a year.

“He hasn’t learned well how to budget money. You give him money and he spends it,” Silverman said. “It’s not that he got enough money to live for the rest of his life and spent it. He got enough money to help him out when he first got out. He got some thousands of dollars that helped support him during this first year, but he clearly, under any scenario, has to work.”

After moving out of the Maré townhome, the Justice Project used donations to pay, upfront, six months rent at an apartment, Taylor said. After several weeks, however, he moved out and lost most of the money put down.

A woman stalking him was the reason for his abrupt move, he said.

A couple of months after his release, Taylor began dating the woman. When it became obvious she was mentally unstable, Taylor said his attorneys helped him get a restraining order against her. She was arrested once at the townhome and turned up again at the apartment soon after he moved in.

Taylor said he felt threatened and that’s why he moved out.

At about the same time, Taylor met a woman who ran a small resale business. She offered him a free apartment in trade for working at her store, he said.

That arrangement lasted only a couple of months. Taylor has now been bunking with friends for days or weeks at a time.

To make ends meet, he recently pawned the bicycle given to him by a supporter.

“His life has been prison,” Silverman said. “It’s bad, but it guarantees you a place to live. It guarantees you three meals a day. It guarantees you clothes. It guarantees you medical care.”

Limited resources

In recent years the Arizona Justice Project has helped free more than a dozen inmates through overturned convictions, exonerations, dismissed charges and other challenges to the legal system. However, limited resources prevent it from providing long-term post-release assistance.

Now Silverman and Arizona Justice Project Founder Larry Hammond, a Phoenix attorney, are considering how to provide for their clients that next level of service.

“If we had the resources, definitely a program like the Justice Project should have a social worker,” Silverman said. “A lot of legal-service-types of programs are learning to have a social work component. Right now the project is just making it (financially) supporting the lawyers who are there.”

Hammond, Silverman and others at the Justice Project are considering options for providing follow-up support, including teaming with college students studying social work.

“It doesn’t suit us to say, ‘Well, our job is done. We got him out. We’re finished,’” Hammond said. “You know these people so long, you share their plight, and when they get out, the nature of the representation changes but the fact of representation doesn’t.”