Born Sept. 2, 1877, in the railroad town of Wells, Nevada, Mary Louise (Louisa) Wade was 2 years old when her family relocated to Mancos Valley, Colorado.

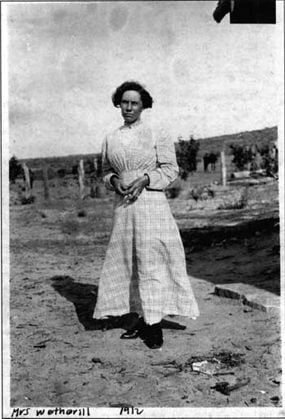

On March 17, 1896, 18-year-old Louisa married 30-year-old rancher John Wetherill. Their son Benjamin was born Dec. 26, 1896, followed by daughter Georgia on Jan. 17, 1898.

Louisa and John made their living running trading posts in Navajo country. Their first store was in Ojo Alamo, New Mexico Territory, followed by another mercantile in Chavez near Thoreau. In 1904, combining inventory from Ojo Alamo and Chavez, they took over a trading post at Pueblo Bonito, about half-way between Thoreau and Farmington. Navajos, Paiutes, and Utes all traded with the Wetherills.

John also ran freight wagons, worked on excavations, and guided expeditions throughout the Southwest, often leaving Louisa alone to run the trading post. She quickly learned the Navajo language and gained the trust of her Native neighbors.

In 1906, Louisa and John headed for Oljato, just north of the Utah/Arizona border in the area now known as The Four Corners. John had convinced the Navajos that a trading post nearby would provide much-needed staples for their people, as well as a place to trade their livestock and wares. Oljato was the first station the Wetherills owned outright.

The couple built their home of adobe, stone, and juniper logs with a dirt roof. Louisa regarded everyone who came to the trading post as her friend. She listened to their stories, sympathized with their grievances, and respected their traditions. The Navajo called her Asthon Sosi — Slim Woman.

Navajo Chief Hoskinini trusted Louisa as he did no other Anglo. She traded fairly and helped tend to the sick if their own medicines did not work. He confided in her and she honored his trust. He considered her his granddaughter.

When he died in 1909, Hoskinini bequeathed all his possessions to Louisa, but she did not feel worthy of keeping his property and distributed it among his family.

Louisa developed an interest in Native herbs and plants collected for medicinal purposes as well as those used for food. With the assistance of medicine man Wolfkiller, she acquired an intense knowledge of these vegetations and eventually accumulated over 300 specimens.

Wolfkiller also taught Louisa Navajo myths, legends, and songs that his grandfather had passed on to him. She translated some of these into English and later, her grandchildren preferred to hear these tales rather than Anglo bedtime stories.

The designs and details of Navajo sand paintings also fascinated Louisa. Drawn on the ground to ward off illness, these intricate paintings made from ground charcoal and pulverized sandstone in colors of red, yellow, and white, were destroyed soon after they had served their purpose. She convinced her Navajo friend Yellow Singer to copy some of these paintings in crayon. The paintings were later reproduced in watercolor by Clyde Coville, a bookkeeper with a knack for trading who lived with the Wetherills for many years.

The Girls Scouts of Southern Arizona ended three days of cookie distribution with their Cookie Drop Friday, January 15, 2021, handing out 6,000 cases - 72,000 boxes - to 57 troops. All told GSSA hope their 2,400 scouts sell 700,000 boxes this year. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

In 1909, Navajo and Paiute guides led John Wetherill and a crew of surveyors, archaeologists, and students to the towering arch now known as Rainbow Bridge, one of the world’s largest natural bridges. Indians knew of the 278-foot span, formed by sandstone erosion from waters flowing from Navajo Mountain to the Colorado River, long before John’s group came upon this environmental wonder, but John and his party were credited with its discovery. Even John dismissed the idea he was the first to know of the bridge, admitting Louisa’s Navajo friends had told her about the giant structure at least a year prior.

In the fall of 1910, the Wetherills opened the Kayenta Trading Post and lodge in the heart of Monument Valley in Northern Arizona. The couple entertained visiting notables such as western writer Zane Gray who patterned some of the characters in his books after Louisa and John. Theodore Roosevelt stopped by in 1913 after a mountain lion-hunting excursion at the Grand Canyon.

The influenza epidemic of 1918-1919 hit the Navajo Nation hard, felling both Louisa and John along with hundreds of local inhabitants. As soon as she was back on her feet, Louisa cared for the Navajos who came to the trading post looking for aid against a disease their own medicine could not cure.

Scientific excursions based out of Kayenta abounded during the 1920s and ‘30s. Movie moguls who recognized that the magnificent sandstone peaks and vast desert provided perfect backgrounds for episodic adventures flocked to the Wetherill lodge. Directors John Huston and John Ford stayed with the Wetherills, along with actor Andy Devine. When Zane Gray’s “The Vanishing American” was filmed around Monument Valley and Rainbow Bridge, Louisa served as technical advisor and designer of Native costumes for the film.

In 1924, while continuing to run the post at Kayenta during the summer months, Louisa and John headed about 70 miles south of Tucson to manage La Osa Guest Ranch during the winter. While John escorted archaeologists and tourists around the state, Louisa catered to the needs of a variety of visitors, including the cast and crew who were filming Harold Bell Wright’s novel, “The Son of His Father.”

After La Osa was sold, the Wetherills returned to Kayenta and continued to welcome personalities such as Ansel Adams whose celebrated photographs captured the beauty of the sand dunes and resplendent sunsets.

For over 30 years, Louisa and John ran the Kayenta Trading Post, living and working with the Navajo people. In 1944, 78-year-old John Wetherill died. History books remember him as the man who discovered Rainbow Bridge.

Louisa sold the property and went to live with her son in Skull Valley outside of Prescott. She died Sept. 18, 1945.

Louisa Wetherill spent most of her lifetime among the Navajo people, traded with them, walked and talked with them, studied their language, their art and their society, and deeply cared about them. She is considered one of the first Anglos to understand and preserve their culture.

Photos: Girl Scouts of Southern Arizona Cookie Drop

Girl Scout Cookie Drop

Updated

Kaycee Livesay, of Troop #247 hands off one of the 300 cases of Girl Scout cookies to John Abbott of Bekins Moving Systems to load into her van at the annual Cookie Drop on January 15, 2021 in Tucson. 2,400 Girl Scouts in Southern Arizona will try to sell nearly 700,000 boxes starting on January 16. Due to the pandemic, Girl Scouts have drive-thru booths, online sales and a partnership with Grubhub for deliveries.

Girl Scout Cookie Drop

Updated

Colleen McDonald adds to a stack of Samosas being counted out for a troop to take at the Girls Scouts of Southern Arizona Cookie Drop, Tucson, Ariz., January 15, 2021.

Girl Scout Cookie Drop

Updated

CEO Kristen Hernandez pitches in, helping load 280 cases of cookies in Brooke Nicholson's pick-up at the Girls Scouts of Southern Arizona Cookie Drop, Tucson, Ariz., January 15, 2021.

Girl Scout Cookie Drop

Updated

Frank Molina from Bekins Moving Systems adds three cases of Tagalongs to walk-up order being filled during the Girls Scouts of Southern Arizona Cookie Drop, Tucson, Ariz., January 15, 2021.

Girl Scout Cookie Drop

Updated

John Abbott of Benkins Moving Systems has to go high to help bring a tall stack of Thin Mints down to size at the Girls Scouts of Southern Arizona Cookie Drop, Tucson, Ariz., January 15, 2021.

Girl Scout Cookie Drop

Updated

Several hands pitch in to help load a trailer with hundreds of cases of cookies at the Girls Scouts of Southern Arizona Cookie Drop, Tucson, Ariz., January 15, 2021.

Girl Scout Cookie Drop

Updated

Yvette-Marie Margaillan tries for the perfect fit in loading 274 cases of cookies on a trailer for Troop #161 at the Cookie Drop for the Girl Scouts of Southern Arizona, January 15, 2021, Tucson, Ariz.