Despite months of preparation, the behavioral health care system in Southern Arizona is once again going through a chaotic transition that’s resulted in millions in unpaid claims to Tucson provider agencies, putting small niche programs at risk of closure.

On Friday, one health plan involved in the debacle was hit with a $125,000 sanction after Arizona’s Medicaid agency, AHCCCS, determined the insurer was in violation of its contract for the claims-processing failures.

The sanction notice said Arizona Complete Health, formerly Cenpatico Integrated Care, wrongly denied $868,000 worth of claims submitted by 12 providers and loaded incorrect reimbursement rates for nearly 2,000 providers into its claims system, among other violations.

The health plan’s failures “resulted in significant adverse impacts to providers of critical services,” which could have been avoided with adequate planning, the notice said.

Some Tucson providers are on the brink of closure after almost four months of trying to absorb losses from unpaid or underpaid claims.

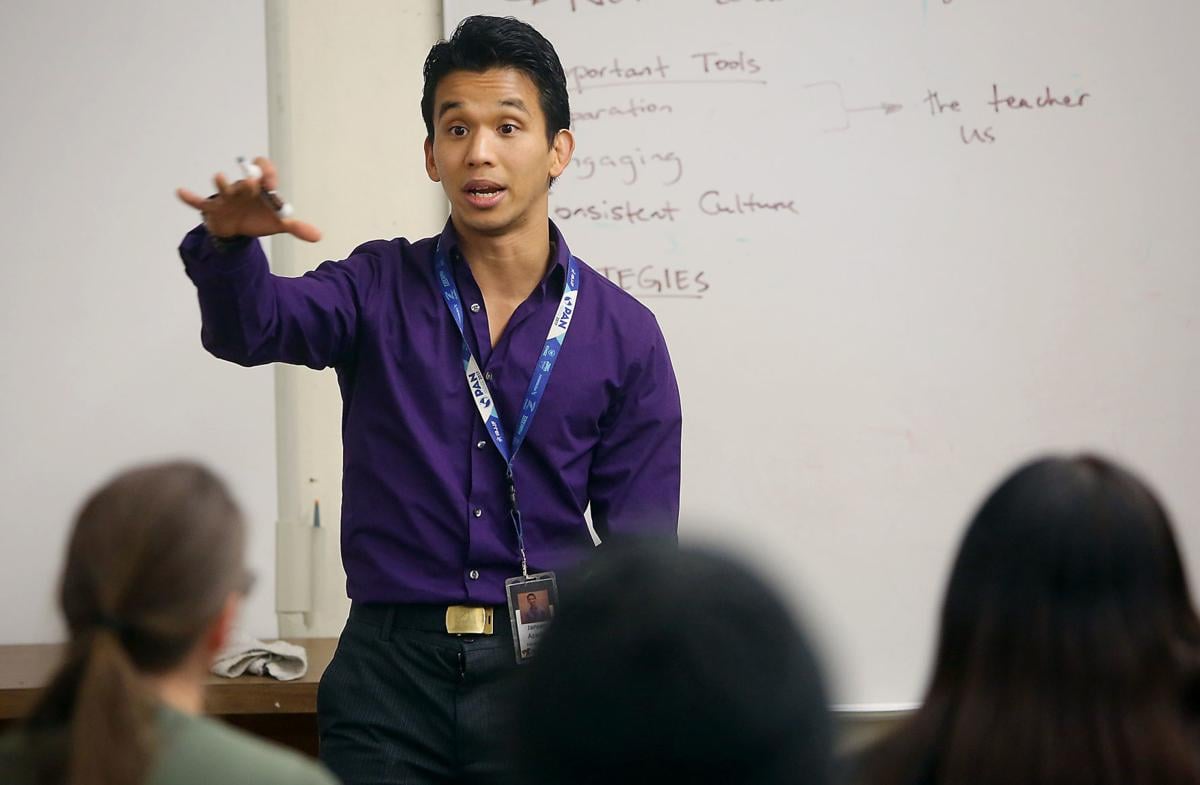

“I don’t think anybody knew it would be this bad,” said Jansen Azarias, CEO of Tucson nonprofit Higher Ground, which provides social-emotional learning to children through activities like martial arts, dance and music.

Two-thirds of the agency’s 30 employees have been furloughed since mid-January, as Azarias had no way to make payroll. Long-term plans for expansion are now in doubt. Azarias said he was prepared to shut down his small agency this weekend, but on Tuesday he received notice of one advance payment that’s supposedly on the way.

“We want to focus on the work, not on this battle,” said Azarias, who started the nonprofit with his wife, Barbara, 11 years ago.

Many of Higher Ground’s children see the program’s activities and staff as the only stable things in their lives, he said.

“This is a waste of our energy to be fighting over contracts, dollars, when, in reality, the community needs services like us,” he said.

The Oct. 1 transition to an integrated physical and behavioral health coverage for people enrolled in the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS), the state’s Medicaid program for low-income and disabled people, brought new insurance plans into the behavioral health arena.

That means new contracts and new reimbursement rates had to be negotiated between provider agencies and insurance companies. But some providers didn’t actually get finalized contracts until as recently as mid-January.

Excessive delays in claims processing, inexplicable rejections of claims, inaccurate payment rates loaded into online claim systems, and poor communication from insurance companies have all contributed to the confusion and financial strain, local providers said.

In the case of one payer, Arizona Complete Health, the online portal for providers to submit their claims was offline for a month, providers said. In its sanction notice, AHCCCS said Arizona Complete Health failed to perform quality testing to ensure its new integrated provider-network database would function on Oct. 1.

“Clearly, the health plans were not prepared,” said Susie Huhn, executive director of the nonprofit Casa de los Niños. “I don’t think there’s any ill intent. I think the health plans are trying their best to get it fixed.”

Although Huhn said her agency is owed about $2 million in unpaid claims since October, the large agency is stable.

“For smaller organizations, if they don’t have three to six months’ cash on hand, this transition could close some doors,” she said.

AHCCCS declined the Star’s requests for an interview. Agency spokeswoman Heidi Capriotti provided a written statement, which said AHCCCS routinely meets with health plans and providers in the community about their concerns.

“AHCCCS is listening to and addressing concerns brought forth by our members, providers and health plans in order to continue to make this transition successful,” the statement said. “Studies show that integrated health care results in marked successes in the areas such as decreased utilization of emergency care, decreased hospital admissions, reduced hospital readmissions, reduced system fragmentation, and reduced member confusion. AHCCCS is committed to the integrated care model and its success in Arizona.”

NEW INTEGRATED SYSTEM

Previously, behavioral health care — including treatment for mental health conditions like depression, as well as substance abuse treatment — was coordinated and paid for by a single Regional Behavioral Health Authority, or RBHA, for each region. In Southern Arizona, since 2015, that RBHA had been Cenpatico Integrated Care.

Under the new integrated care structure, Cenpatico — now Arizona Complete Health, after its merger with Health Net of Arizona — is one of three insurers in the region providing coverage that includes both physical and behavioral health care. The other two Southern Arizona integrated health plans are Banner University Family Care and United Healthcare Community Plan. (Those with a diagnosis of “serious mental illness,” as well as other groups like children in foster care, are still covered under the RBHA system.)

Most AHCCCS members were randomly assigned to one of the three new health plans.

Officials from Banner and United declined the Star’s requests for interviews about the problematic transition, and Arizona Complete Health spokswoman Monica Coury did not respond to the Star’s interview requests.

La Frontera Arizona is owed more than $4.6 million in unpaid claims for services provided since October, said Dan Ranieri, CEO of La Frontera, one of the biggest behavioral health agencies in town. Some of that has been offset by advance payments — which must be paid back — from Arizona Complete Health, he said.

“Everybody’s kind of holding on. It’s kind of like living off of your retirement funds and when they’re gone, they’re gone,” he said. “If you’re a small provider with no cash, this has really been disastrous.”

The Arizona Council of Human Services Providers is working with AHCCCS to ease the pain of this transition, said Emily Jenkins, president and CEO of the council, which advocates for its member agencies.

Small providers often provide niche services that can’t be found elsewhere, and they are hit hardest by payment delays, she said.

“We’re going to talk about what we can do to relieve that burden on the providers,” she said. “If we start losing providers, then we get into issues around access to care, issues around having an adequate network. Unfortunately, some of the smaller providers are more specialty providers, and they’re often people we really need to have in the network.”

ACCESS TO CARE

Advocates for people with mental illness worry that ongoing confusion and short-staffed provider agencies will soon mean less access to care for vulnerable patients.

Some patients are already feeling the effects, said Clarke Romans, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Southern Arizona, which has laid off about one-third of its staff because of payment reductions from Cenpatico over the past couple of years. The insurer did not renew its contract with NAMI last year, for unclear reasons, Romans said.

NAMI, which provides peer support for people with mental illness and their family members, often works as a liaison between insurers and their clients.

NAMI representatives have heard about patients struggling to get their medications, being discharged prematurely from crisis facilities and hospitals, and getting less individualized care, Romans said.

Without case managers to follow up with patients, who may have no one to advocate for them, “many of these folks fall through the cracks,” he said.

But some of these problems have less to do with the current payment problems than with the insertion of for-profit insurers into the public behavioral health care system in recent years, he said.

“These are the outcomes of this kind of business model of simply squeezing the providers so that a better profit margin can be maintained,” he said.

Rod Cook, CEO of COPE Community Services, said he’s heard about patient-care issues, too. Insurers are now requiring prior authorization for residential treatment stays, making it difficult to get longer stays approved. That’s resulting in more emergency hospitalizations after unstable patients are released too soon and go into crisis, he said.

Ranieri said the local community is “teetering on the edge” of access to care becoming a problem for patients. But the most likely outcome is continued consolidation in the behavioral health industry, he said.

The latest example: Last September, in an effort to survive anticipated payment-rate cuts, Intermountain Centers for Human Development acquired Community Partners Inc. The acquisition came about 18 months after Community Partners acquired Assurance Health & Wellness, out of similar financial concerns.

Once the recent payment issues are resolved, provider agencies will still need to figure out how to make their businesses work with lower reimbursement rates, said Rose Lopez, CEO of Intermountain. For a long time there have been too many providers in the Tucson area, and so some closures and mergers may be necessary, she said.

“We can’t just sit back and provide general mental health anymore,” she said. “It’s almost like we have to move into specialty areas to some extent. We have to look at, how do we diversify our revenue streams? That growth and development takes cash.”

Lopez said her agency is owed millions by the three health plans, but she would not specify how much. Lopez said the insurers have been working closely with her agency to resolve the issues, and she’s optimistic that the new integrated health plans will mean better care coordination for patients.

“I do think that we needed change,” she said. “I do think there is an opportunity for the care to improve under this new system.”

Cook said he’s less optimistic that care coordination will improve in the chaotic new landscape. Insurers have moved away from upfront block payments — in which agencies get a monthly payment for each enrolled patient, he said. But those “per-member, per-month” payments gave agencies an incentive to find the best and most cost-effective treatment for their patients, allowing those working closely with patients to manage their care on an individualized basis, he said.

Insurers have now moved back to a fee-for-service model, in which agencies are paid based on the volume of services provided, he said. Under this model, there’s basically no management of care from the so-called “managed-care” insurance companies, he said.

“I just don’t know what the grand vision is here,” Cook said. “A fee-for-service model is the most antiquated model of health payment there is. There’s a lot of potential for abuse in that. You could provide service after service to get paid. You can make your bottom line work, but is anybody really getting better?”

RATE CUTS

Rates paid for services by psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners have been dramatically cut under the new payment structure, agency leaders said.

The cuts have resulted in a loss of some psychiatrists at CODAC Health, Recovery & Wellness. Those professionals are already in short supply in the public behavioral health care sector, said CEO Dennis Regnier. The agency is owed $5.8 million in unpaid claims.

Lower reimbursements makes it harder for nonprofits serving those covered by AHCCCS to retain those specialists, who are being recruited by the private sector, too, he said.

CODAC tried to prepare for the transition last year, including closing a service location at Broadway and Country Club and shutting down two five-bed residential treatment centers for people with serious mental illness. It stopped providing employees with cars to search for hard-to-reach clients on the streets and in desert washes in order to transport them to appointments.

The agency also cut 10 positions around October. The cuts come after years of turmoil and rate cuts, which had already prompted CODAC to cut about 100 positions since April 2017 to ensure the agency’s survival, Regnier said.

“Every month you don’t make some changes, it just compounds the ultimate outcome,” he said. “It’s really hard to be the employer we want to be sometimes.”

Caseworker Patrick Ohlde, who has worked in Tucson’s behavioral health field for eight years, said he was laid off from CODAC just before the Oct. 1 transition.

He’d worked as a “dedicated recovery coach,” a high-level caseworker seeing patients who were court-ordered to receive mental health treatment. Staff working with those high-needs patients were supposed to have max caseloads of 25 patients, but Ohlde said his caseload at some points reached more than twice that amount due to already inadequate staffing levels and turnover in the high-stress job.

“When you have 50 people on your caseload, it’s just impossible to see everybody once a week,” he said. “It puts you in a precarious position.”

Under the new insurance companies, case management coverage has been dramatically limited, Ohlde said. He worries that lack of follow-up with struggling patients will cause some to spiral into crisis.

“It becomes a safety issue, not just for the members we’re serving, but for the community as well,” he said.

He recalled one patient who stopped showing up for appointments, prompting Ohlde to reach out to him more persistently and visit him at home. The patient later told Ohlde that on one of those occasions he was about to take his own life — but the visit from Ohlde is what stopped him.

“Those are the stakes we’re dealing with,” he said. “It can escalate very quickly.”

PROFITS FOR PARENT COMPANY

For almost 20 years, Southern Arizona behavioral health agencies had the same Regional Behavioral Health Authority payer: a Tucson-based nonprofit called Community Partnership for Southern Arizona. Advocates and agency leaders say the last few years have been marked by constant change and turmoil since Cenpatico, now Arizona Complete Health, won the RBHA contract with AHCCCS.

Cenpatico recorded an $8.4 million profit in fiscal year 2016, its first full year in the Southern Arizona market. But it experienced a dramatic downturn in 2017, losing $5.3 million, according to the company’s most recent year-end financial report.

Coury, the spokeswoman for Arizona Complete Health, did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the company’s finances.

Meanwhile, profits have exploded for the insurer’s publicly traded parent company, Centene Corp.

Centene, based in St. Louis, has become a Medicaid managed-care powerhouse since the 1990s, largely through securing government contracts. Centene increased its net earnings from $161 million in 2013 to $828 million in 2017, according to Centene’s 2017 annual report. Over that period, Centene grew enrollment in its managed-care plans from 2.9 million to 12.2 million members.

Another Centene subsidiary, Centurion, now has a presence in Tucson, providing health care for inmates at Pima County adult and juvenile detention centers after the Board of Supervisors approved a $50.6 million, three-year contract last May.

As the Star has reported, Cenpatico contracts with many of its sister companies that are also subsidiaries of Centene. That includes Envolve Pharmacy Solutions, formerly U.S. Script, which provides pharmacy-benefit management services, and Envolve PeopleCare, formerly NurseWise, which does nurse triage and crisis services.

In fiscal year 2017, Cenpatico paid $99.4 million to seven of its sister companies operating in Arizona — a 14.6 percent increase over payments to those companies the year prior, according to its financial report. Much of that increase came from its payments to Centene Management Co. Those administrative expenses more than tripled from $4.8 million in 2016 to $14.8 million in 2017.

Cenpatico received more than $685 million in fiscal year 2017 through its contract with AHCCCS, a 6.9 percent increase over the previous contract year.

AHCCCS spokeswoman Capriotti said the agency’s RBHA contracts allow insurers to devote up to 10 percent of their AHCCCS funding to administrative costs, and Cenpatico has not exceeded that limit.

Centene Chairman and CEO Michael Neidorff got a $25.3 million compensation package in 2017, including a $1.5 million base salary, $7.1 million in bonuses and $16.1 million in stock, according to Centene’s latest proxy statement.

“It feels like we’re being robbed,” said Higher Ground’s Azarias, whose program serves 2,000 children on its $1.5 million annual budget. It is owed $95,000 in unpaid claims from the health plans.

“We don’t need an insane amount of money. I can understand if these insurance companies, if they’re struggling, too,” he said. “That’s not what happening.”