PHOENIX — Pima County’s top prosecutor is seeking a delay in the bid by Attorney General Mark Brnovich to set an execution date for Tucson killer Frank Jarvis Atwood.

But in a spat that is pointing up a divergence of views on capital punishment, he is spurning her request.

In a letter to Brnovich obtained by Capitol Media Services, Laura Conover said that since taking office in January she is reviewing a number of cases, including those on death row, because an “unfortunate” history of the department she said led to disbarments and appellate cases “born out of prosecutorial misconduct.”

“Now that my name is attached to all the work of the office, I need to undertake a review to be certain we haven’t overlooked anything,” she wrote. Conover said she wants to “put to rest the history here out of the old homicide and capital units.”

Conover is not seeking to overturn the death sentence imposed on Atwood, a previously convicted pedophile, who was convicted of the 1984 slaying of Vickie Lynne Hoskinson. She disappeared while riding her pink bicycle on her way to mail a letter for her mother.

Authorities eventually tracked Atwood to Texas where he was arrested on charges of kidnapping. Murder charges were added after Vicki’s skull and some bones were found in the desert northwest of Tucson the following year.

Atwood has continued to maintain his innocence, even after exhausting all appeals. He contends police planted evidence, including testimony that pink paint on the front bumper of Atwood’s car had come “from the victim’s bike or from another source exactly like the bike” and that Vicki’s bicycle had nickel particles on it that were consistent with metal from the bumper.

“By no means do I want to cause undue delay,” Conover wrote Brnovich. “But I think we will all be well served by a temporary hold on any death warrants from Pima cases while we put to rest the history here out of the old homicide and capital units.”

Brnovich dismissed her request.

Part of it, he wrote, is because the Atwood case was handled by someone from his office and not Pima County, “rendering any proposed review of this case by you unnecessary, as well as untimely.”

That, however, is only partly correct.

John Davis actually started handling the case when he was a deputy Pima County attorney. He was allowed to continue handling the case when he went to the state Attorney General’s Office.

Brnovich, in his response to Conover, also took a slap at her for making the request in the first place.

“I am concerned that your letter is less about an internal review and more about ending the death penalty in general,” he told her, noting that she campaigned on a platform of ending capital punishment. Brnovich said that it is her right, as the county attorney, to decide when to seek the death penalty.

“As attorney general, I am charged with enforcing the laws of Arizona, including carrying out capital punishment sentences,” he said. “I also take seriously the finality of jury verdicts, as well as the constitutional right afforded crime victims to a prompt and final resolution of a criminal case.”

Atwood

Joe Watson, spokesman for Conover, acknowledged that her reference to “disbarments” of attorneys may have been overstated.

Only one prosecutor was disbarred after it was determined that he had allowed a police officer to lie on the stand in two murder cases. But Watson said other prosecutors had their law licenses suspended.

But Watson said there is a “volume of misconduct” by prosecutors that has been detailed when appellate courts reviewed Pima County cases. That, he said, “could result in a lengthy review, especially in the homicide and capital case arena,” the review that Conover wants to conduct before anyone else convicted in her county is put to death.

Watson acknowledged the opposition of his boss to the death penalty and her decision not to seek it in future cases.

Part of that, he said, is based on her campaign promises. But Watson said that the move also frees up the attorneys assigned to capital cases to focus on the backlog of other homicide cases that had accumulated before Conover took office.

And there’s a philosophical element to it, too.

“The death penalty perpetuates ongoing trauma to victims and their families,” Watson said. And then there’s the fact that “mistakes can happen, evidence can get lost, and science can fail us.’’

He also said that, at least in Pima County, the overwhelming sentiment is to stop seeking the death penalty.

The questions Atwood’s attorneys want the Supreme Court to address go beyond questions of the propriety of capital punishment. One of those issues is the timing — and the schedule that the attorney general wants to set.

Brnovich has said there are about 20 people on death row who have exhausted all their appeals. Yet he chose to seek warrants of execution against just two: Atwood and Clarence Wayne Dixon, who was convicted of killing Deana Bowdoin, an Arizona State University student, in 1978. Other Death Row inmates exhausted their appeals even earlier than Atwood and Dixon.

Joe Perkovich, another of Atwood’s attorneys, told Capitol Media Services he thinks the rush with his client has to do with a bid by Brnovich to preclude a pending issue from being legally resolved.

Under Arizona law, the death penalty can be imposed only when there is at least one “aggravating factor.” That can include things like whether the murder was committed for financial gain or whether it was done in an especially cruel and heinous fashion.

In Atwood’s case, there was only one aggravating factor: a prior conviction from California. But Perkovich said the Supreme Court needs to resolve whether that out-of-state conviction can be used as a reason to sentence someone to death for an Arizona crime.

That issue, he said, was not raised at the time of the trial and sentencing but only recently when Atwood’s attorneys asked Pima County Superior Court to take a look.

The attorney general’s office said that claim was dismissed, though Perkovich said that proceeding was shut down because of the pandemic. And Perkovich said that Brnovich wants to hurry along Atwood’s execution before there can be a full hearing on the matter.

Ryan Anderson, a spokesman for Brnovich, said he can’t comment on the charge, saying these issues will be addressed in future court filings.

But Kevin Heade, president of Death Penalty Alternatives for Arizona, said there’s something else in the decision to move the Atwood and Dixon cases to the front of the line. In both cases, he said, the families of the victims have been very vocal in their support of the death penalty.

Hoskinson’s mother, Debbie Carlson, has been particularly vocal, both publicly thanking Brnovich “for standing with us in our quest for justice” and pressuring Gov. Doug Ducey to have the state Corrections Department procure the necessary drugs to execute Atkinson.

Heade said Brnovich putting those two up first “reeks of political opportunism so that he can demonstrate commitment to victims’ rights.”

Anderson dismissed the allegation.

“This is about justice, period,” he said.

There is a more specific legal question: Do the justices have the ability to delay an execution.

In his own filing with the court, Brnovich says the only thing they have to determine is whether there has been a conclusion to Atwood’s first post-conviction proceeding and any appellate review.

“If those proceedings have terminated, as the state will show, the relevant statute and procedural rule, respectfully, leave this court no discretion to deny the warrant,”

Atwood’s attorneys are asking the justices to reject that claim, saying that it would reduce the court to “a rubber stamp acting at the direction of the executive department.”

“And there would be no independent check on the attorney general’s ability to set execution dates,” the pleadings say.

It isn’t just Atwood seeking a delay.

Attorneys for Dixon have filed their own request. But unlike Atwood, the claims are much narrower. They have to do with the inability of the lawyers to get with their client due to COVID-19 restrictions to discuss things like preparing to go before the Board of Executive Clemency.

Photos: The search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson in 1984-85

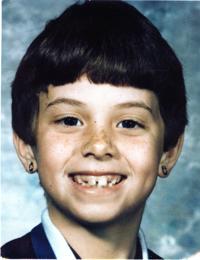

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's deputies talk to children in the neighborhood near where Vicki Lynne's bicycle was found during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's Det. Gary Dhaemers talks with neighborhood resident Vickie Marshall during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Undated photo of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, who was murdered by Frank Jarvis Atwood in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's deputies check for physical evidence during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A Pima County Sheriff's deputy talks to a neighborhood boy during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 17, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Volunteers coordinate their search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff's detectives coordinate their search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on Sept. 18, 1984 near Homer Davis Elementary School on Romero Road, Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Law enforcement officers during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, 8, in Tucson in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A billboard for missing girl Vicki Lynne Hoskinson in Tucson in 1984.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Pima County Sheriff Clarence Dupnik, left, speaking at during a press conference on Sept. 20, 1984, to announce the arrest of two men in connection with the abduction of Vicki Lynn Hoskinson. Others pictured: County Attorney Steve Neely and FBI agents Dick Swinson and Richard Rogers.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

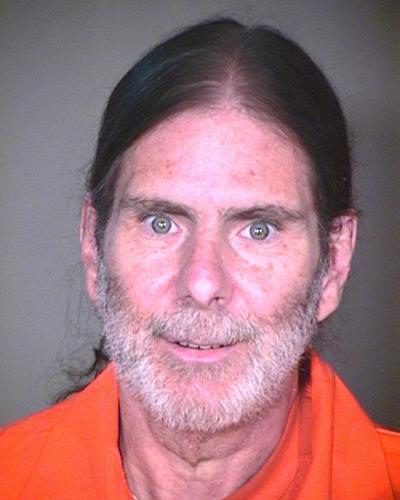

Arraignment of Frank Jarvis Atwood in 1985. He was charged with first-degree murder in connection with the death of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Thelma Hoskinson, right, grandmother of Vicki Lynn Hoskinson, cries during a press conference on Sept. 20, 1984, announcing the arrest of two men in connection with Vicki Lynne's abduction and death.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

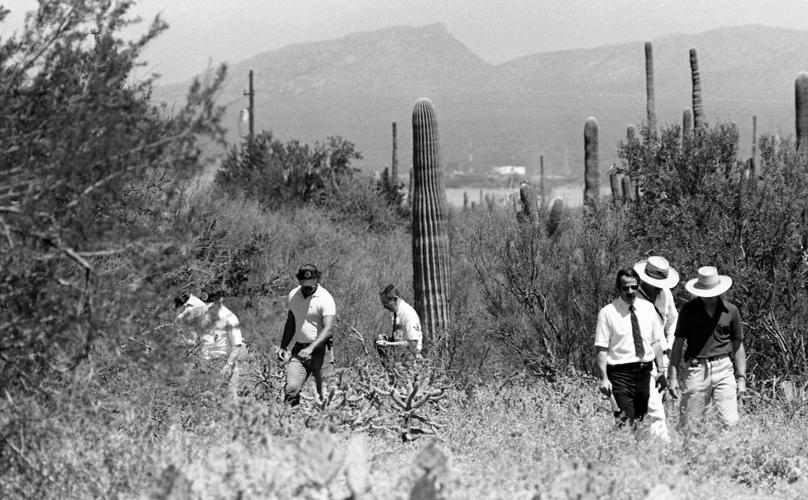

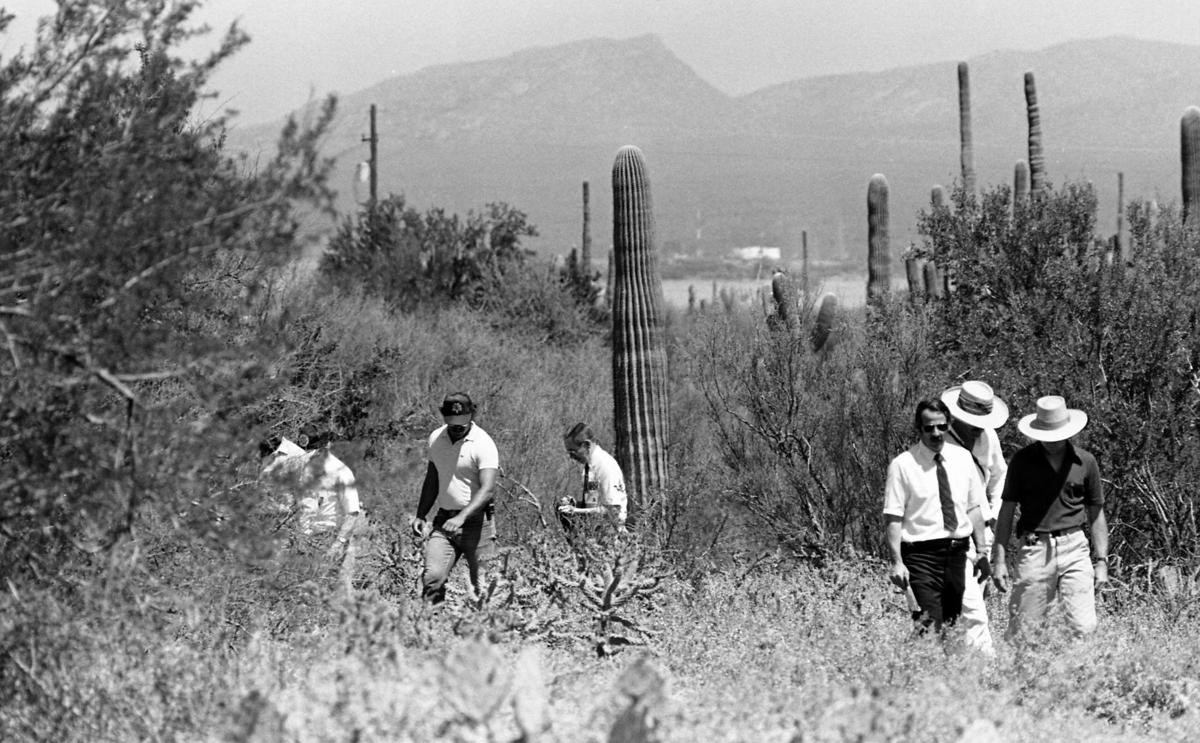

Forensic investigators from the PIma County Office of Medical Examiner and the University of Arizona survey an area where the bones of a child were found that were thought to be those of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 15, 1985

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Forensic investigators from the PIma County Office of Medical Examiner and the University of Arizona survey an area where the bones of a child were found that were thought to be those of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 15, 1985

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

The Arizona Department of Public Safety helicopter hovers during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Members of Southern Arizona Rescue Association and Pima County Sheriff's deputies coordinate search during for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

A member of the Pima County Sheriff's Posse on horseback rides west on Ina Road during the search for Vicki Lynne Hoskinson on April 12, 1985 at the end of Ina Road, west of Interstate 10.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Children cry as the casket of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson is carried during graveside services on May 30, 1985 at Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson.

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson

Updated

Debbie Carlson collapses in grief over the casket with the body of her daughter, Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, during graveside services on May 30, 1985 at Evergreen Cemetery in Tucson.