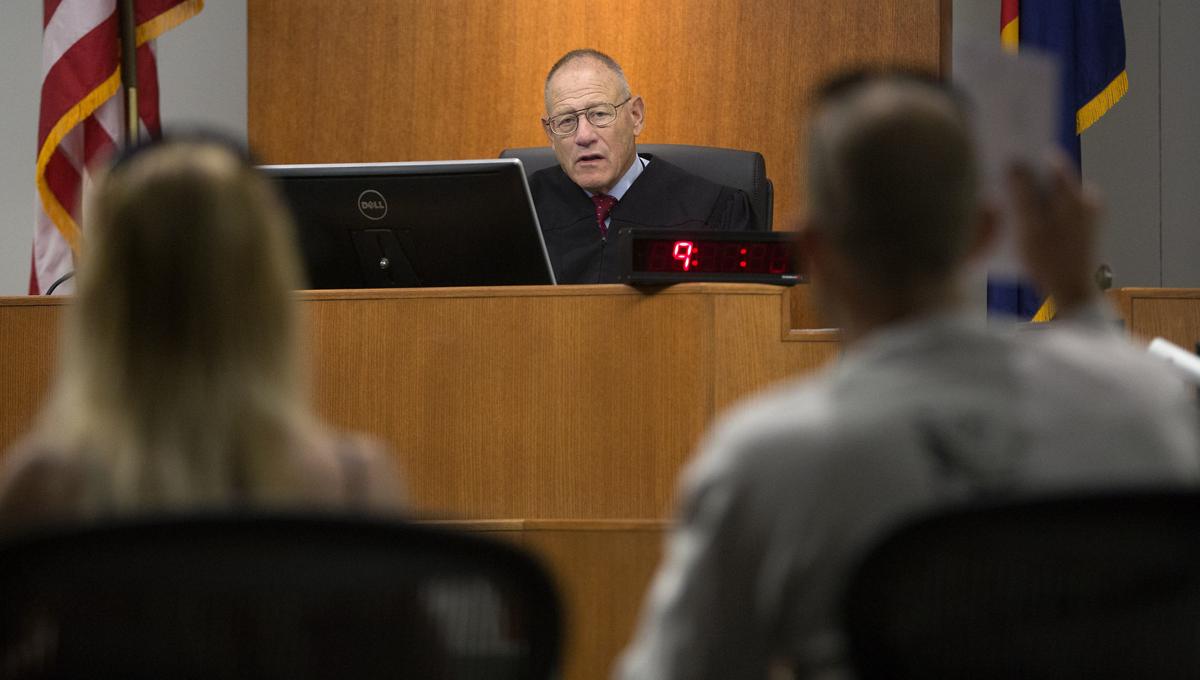

Judge Ronald Newman took the bench before a small crowd of property owners, lawyers and embattled tenants gathered at Pima County Consolidated Justice Court, where about 13,000 eviction filings are adjudicated each year. During busy times of the month, Newman can hear more than 100 eviction cases in a day.

Of the first 25 tenants facing eviction on this October morning, less than half showed up for their hearing — an unusually high turnout. Those who were absent lost their case by default and got an eviction on their record. Of those who did appear, none had an attorney with them.

On this morning, Newman asked tenant Joanne Kofoed, 42, whether she agreed that she owed September and October rent. Joanne agreed and told Newman that she’d recently moved from Texas. A road trip back to Houston to pick up her sick mother, and the rest of her belongings, ended up costing thousands more than she’d planned.

Joanne said her landlord wouldn’t accept the partial rent payments she’d offered to hold her over until her next paycheck came in. (Under Arizona statute, property owners don’t have to accept partial payments.)

“They know I get paid tomorrow, and I’d be able to pay the full amount tomorrow,” said Joanne, a retention specialist at a local call center.

Newman was understanding, but resolute. “If I had to make the choice between paying rent and taking care of my mother, I would do the same thing,” he said. “Unfortunately, I have to follow the law as it is.”

Newman ordered the eviction based on nonpayment of rent and encouraged Joanne to try to work things out with her landlord. But the outcome was now out of her hands: Since the eviction was already approved, the property owner had full discretion on whether to accept her late payment or to evict her.

Nearly three-quarters of eviction actions filed in Pima County Consolidated Justice Court over the last four years were ruled in favor of the landlord, an Arizona Daily Star analysis of Justice Court data found. About a quarter of the eviction filings in that period were dismissed by a judge.

While eviction is an important tool for property owners to be able to get rid of bad or nonpaying tenants, the process is vulnerable to abuse.

Eviction proceedings are fast-moving and can be baffling for those without legal experience. Of the tenants who do show up to the hearing, maybe 5 percent have a lawyer helping them, Newman said. The vast majority of landlords are represented by an attorney specializing in landlord-tenant law.

Most tenants don’t even show up for their hearing. Some can’t get the time off work or don’t have transportation. Some feel intimidated or hopeless that their presence would make any difference. Others show up a few minutes late to find their hearings have already been heard and decided in seconds. Legal-aid attorneys say judges tend to delay hearings if a landlord’s attorney is running late. A Star reporter witnessed one hearing delayed an hour until a landlord’s lawyer arrived.

Tenants who do appear sometimes quickly admit to the judge that they owe rent and usually, after that confession, anything else they say is a moot point. But tenants can get a follow-up trial if they raise objections that constitute a “factual dispute,” perhaps explaining their landlord refused to accept rent or didn’t give proper notice, or showing evidence that the amount owed is less than the landlord claims.

But if the tenant fails to make a case, or focuses on details that have no legal relevance, a valid argument may go unheard, housing attorneys say.

Without a lawyer, “A tenant will present facts to the court that have absolutely no bearing on the case,” said James Daube, housing attorney with Southern Arizona Legal Aid, which offers free legal services to qualified low-income clients. The court often treats a tenant’s failure to contradict their landlord’s allegations “as essentially, an admission to those facts,” he said.

Newman said he takes pains to help tenants without an attorney understand the process, but as a judge, he’s limited in what he can say. For instance, he can’t advise a tenant to object when a landlord uses hearsay in his or her testimony.

Even though eviction cases are often heard and adjudicated in a couple minutes, Newman emphasized that judges don’t rush through cases.

“We don’t rubber-stamp it,” he said. “If we think there’s a reasonable basis to question allegations in the (landlord’s) complaint, certainly my job as a judge is to afford everyone their rights under the law. I don’t care how long it takes.”

But legal advocates say the quick pace of the hearings gives judges little time to discern between lawful and unlawful eviction filings. And while many landlords are fair, there are plenty of “bad-faith” filings: Unscrupulous landlords seeking to oust an outspoken tenant sometimes refuse to accept rent payments, then file an eviction action alleging lack of payment. Others don’t give receipts for rent paid in cash or with money orders, and allege nonpayment even when rent has been paid. Some landlords reimburse rent that has been paid electronically before filing an eviction, charge exorbitant late fees or they overstate how much they are owed in Justice Court.

JUSTICE COURT CHANGES

Judge Newman said he’s passionate about his work in Justice Court, which handles civil cases with claims of less than $10,000, including evictions and traffic violations, as well as some criminal cases.

The lower courts are “where the majority of our citizens are exposed to our legal system,” Newman said. But emotionally, the work can be difficult, he said. He recalled ordering the eviction of an elderly woman who was losing her home of 18 years after getting laid off.

“You’re dealing with heart-wrenching situations, in some cases,” Newman said. “I can’t fathom suddenly not knowing where I’m going to live, particularly if you’re a parent with young children. What are you going to do?”

Newman, a retired attorney, is a “judge pro tempore,” appointed by the Board of Supervisors. The part-time, hourly pro-tem judges almost always handle the initial hearings on eviction actions. Full-time, elected justices of the peace will sometimes hear eviction trials. Neither justices nor judge pro tems are required to be attorneys.

Under recent changes in Justice Court scheduling, two experienced judge pro tems — Newman and Judge Cecilia Monroe — preside over almost all eviction hearings in a consolidated schedule, with all eviction cases typically confined between Tuesday and Thursday. The judges will extend their hours on those days, said Micci Tilton, deputy court administrator.

“It’s not that we’re shoving more cases into an hour,” she said. “We’re making sure we’re filling up our day before we move to the next day.”

The changes should ensure consistency in the judges’ interpretation of housing law and more continuity in oversight of cases, Newman said. If an initial hearing warrants a follow-up trial, Newman can schedule that trial for his own calendar, so he’ll already know the case background.

After Joanne’s landlord secured an eviction order against her during the Oct. 18 court hearing, it was up to the landlord’s discretion whether or not to accept her late payment or carry out the eviction order. Reached by phone the day after the hearing, Joanne said her paycheck had come through and her landlord accepted her payment.

The now-vacated eviction action cost her hundreds more in court costs and attorneys’ fees, Joanne said.

“I’ve had nightmares for the last week,” said Joanne, who experienced homelessness in California after her personal chef business failed during the Great Recession, in 2008.

“I understand these landlords are trying to make money like we are, trying to feed their families. But if they could at least understand and have some compassion, we might be able to understand one another and work things out” before going to court, she said. “I think all of this was just a waste of time and energy and money.”

LANDLORD PERSPECTIVE

Tucson landlord Eden Tretschok has real estate in her blood. In the 1960s, her parents drew the plans and laid the bricks themselves on the 34-unit Carlton Apartments at Speedway and Columbus Boulevard. They had their three children read up on the Arizona Landlord-Tenant Act starting in junior high, she said. Tretschok now owns and manages the property, and a few other single-family homes in town.

“I want to do it right,” she said in July. “I had three air conditioners go out yesterday, on the hottest day on record. All of them were fixed by 5 p.m.”

Property management is a labor of love, she said, but it’s getting harder. Tenants seem to be more entitled and take less pride in their homes, she said.

“I can’t give you concierge service,” she said. “I’m not your butler, your friend, your therapist. And they want all of that, while they’re destroying my property.”

After the housing crash, foreclosures flooded the rental market, leading to higher vacancies and lower rents. The opioid epidemic has had a noticeable effect on her tenants’ lives, resulting in destructive behaviors Tretschok said she hadn’t seen before.

“Those two things happening changed the rental market in Tucson,” she said. “It has become progressively worse. I have to rent to people I wouldn’t have rented to 10 years ago.”

But Tretschok said she’s willing to take chances on people with checkered pasts.

“Nine out of 10 ex-cons — the ones that know it’s their second chance — are the best tenants you could ask for,” she said. “Sometimes you take a chance and it works.” Other times, “The person who looks good on paper is nothing but a nightmare.”

That includes a recent tenant she evicted after a stabbing took place in the apartment. Before that, the woman reported electrical problems that she herself caused after overloading the circuitry, Tretschok said. Then the tenant couldn’t find time to let in the electrician for two weeks and in the meantime, the tenant and a friend made a failed attempt to rewire the breaker themselves, then withheld rent due to the electrical issues, Tretschok said.

Tretschok said she’s had tenants threaten her and change the locks so she can’t come in. One family brought in bedbugs with used furniture, then stopped paying rent due to the pests, she said.

Evictions are a last resort, Tretschok said. She said she once let a family stay rent-free for seven months because she wanted their kids to finish the school year.

But, she said, “There comes a time when the fact that my heart doesn’t want their kids on the street, and my wallet, don’t meet anymore.”

EVICTION TIMELINE

The eviction process happens rapidly in Arizona compared to other states. While in California evictions take a minimum of two months, in Arizona the process can be completed in a little more than two weeks, Newman said.

But property managers say the process isn’t quick enough. From the time renters first miss their rent payment, it can take 30 to 45 days to go through the eviction process and then get a new tenant into the property, said Melanie Morrison, board member of the Arizona Multihousing Association and principal at MEB Management. All the while, the vacant property is losing money.

“The clock starts ticking when rent is not paid for the month,” Morrison said. “For landlords, you don’t want somebody to be evicted. You have to completely prepare the apartment again for the next renter, you have vacancy loss. I think it’s in everybody’s best interest if you can help someone not be in a situation to be evicted.”

An eviction usually starts when a landlord delivers a five-day “pay or quit” notice: The tenant must pay rent owed within five days, plus any late fees, or give up their tenancy. If the tenant doesn’t pay or return their keys in five days, the landlord can file an eviction action. The court will then set an initial hearing within the next three to six days to determine if there’s any defense on the tenant’s side. With that paperwork filed, a tenant would now have to come up with rent owed, late fees, plus attorneys’ and court fees in order to avoid the eviction hearing.

If the landlord wins an eviction, he or she can insist the tenant vacate the property after five days. Then, the landlord can get a “writ of restitution” allowing the precinct’s constable to forcibly remove the tenant and change the locks. Usually that’s unnecessary and the tenant leaves voluntarily.

In many cases, legal-aid attorneys get a desperate call from a renter a day or two before their initial eviction hearing is scheduled. Perhaps the eviction notice was mailed to the wrong address or wasn’t properly served. Sometimes tenants are too overwhelmed to think about how and where to find a lawyer they can afford.

“The whole process happens so quickly here that it’s hard to see how it can be considered fair,” said Matthew R.K. Waterman, managing attorney at Southern Arizona Legal Aid. “It’s stacked against the tenants. You don’t have the ability to mount a defense.”

Newman said it’s common for landlords to give improper notice that doesn’t meet statutory requirements. He once threw out an eviction case because the only notice the landlord gave before filing for eviction was a note taped to the tenant’s door: “Get the hell out of my apartment if you don’t pay your rent.”

Tenants often withhold rent because their landlord refused to make repairs to the property. But that’s not a valid defense for nonpayment of rent, Newman said. To stay within the law, a tenant must put the request in writing and give the landlord 10 days to remedy the problem. If the repairs would cost less than $300, the tenant can hire a licensed contractor to make the repairs and deduct the cost from their rent, after giving written notice.

Newman said he’ll “bend over backwards” to see the tenant’s side. Even if they’ve just sent text messages asking for the repairs, he will accept those as written notice if the tenant prints out the messages before trial, he said.

With the help of a legal-aid attorney, Milton Kline and his girlfriend, Judy Turner, defeated an eviction which Kline said his landlord filed in retaliation for Kline reporting possible mold.

FIGHTING BACK

Milton Kline, 58, an Air Force veteran, wasn’t willing to accept the eviction filed against him without a fight. But he doubts he would have prevailed without the help of a lawyer.

As a four-time felon, Milton says finding housing has been a challenge. His life started to spiral downhill after he got out of the Air Force in 1985 and a series of difficult life events derailed him. First, he accidentally shot himself in the eye with a nail gun. Then his wife left him, taking their two children, and his father died, all in one year.

“I couldn’t handle it,” he said. “It was too much.”

He said he turned to drugs, primarily cocaine and meth, accumulating drug-possession charges and an attempted-burglary charge.

After his last stint in prison, which ended four years ago, Milton said he reconnected with family and began to turn his life around. He said he’d been living at Roger Plaza, a mile south of Tucson Mall, for about three years before the trouble started earlier this year.

A leak in a neighbor’s apartment caused water to seep into Milton’s place. Over time, Milton suspected a black mold problem had developed. His cat died, and his girlfriend, Judy Turner, who has a lung condition, struggled to breathe and broke out in hives when she came over.

After his landlord, Andy Pongratz, didn’t address the suspected mold, Milton said he reported the issue to the HUD-VASH program, which provides housing assistance to veterans and covered his $680 rent. The Section 8-style program sent a city inspector to his apartment.

Milton said his relationship with his landlord was friendly for most of his time at Roger Plaza, until he called the housing inspectors.

After leaving an apartment where a landlord tried to evict them, Milton Kline and Judy Turner struggled to find a landlord who would accept a housing voucher.

“The whole temperature changed,” he said.

Pongratz denies there was any mold in the apartment, and he maintains Milton was a disruptive tenant with a messy front porch and tons of foot traffic passing through.

“Anybody he’d see on the street, anybody that needed a glass of water, anybody that needed a sandwich, he invited into his apartment,” Pongratz said in an August interview in his Roger Plaza office. Pongratz also said Milton’s visitors were threatening, and he displayed a photograph of a man carrying a baseball bat to prove his point. (Milton said his friend was actually playing baseball.)

The April 9 city inspector’s report noted “suspected mold” in Milton’s apartment and ordered the landlord to provide documentation from a professional mold-detection company stating the unit is free of mold. A May 3 reinspection report indicated the unit again failed inspection.

Soon afterward, Pongratz served Milton with 10-day notices alleging a messy front porch that constituted a fire hazard, intimidating and threatening behavior and undesirable guests. He filed notices asking for an immediate eviction, alleging a material and irreparable breach of the lease, which would allow for a quicker eviction process.

Outraged by what he saw as retaliation, Milton said he contacted attorneys at Southern Arizona Legal Aid.

Attorney James Daube said he got the call from Milton the day before his eviction hearing. Southern Arizona Legal Aid only takes cases that are “meritorious,” and there are more of those than the law firm can handle, he said.

In Milton’s case, “I informed the court we would deny any allegations and we were counterclaiming for retaliation, on the grounds that he filed this action and served these notices essentially to punish Mr. Kline for reporting the mold issue.”

Daube said he defeated the eviction because the landlord wasn’t able to prove his allegations against Milton during the trial, which ended up being held on the same day as the initial hearing. While the judge was bothered by the timing of Pongratz’s eviction notice, he didn’t find sufficient evidence of retaliation in the counterclaim, Daube said.

Defeating the eviction was only the first challenge. Milton and Judy said they made hundreds of calls to try to find a place that would accept Milton’s HUD-VASH voucher. After they left Roger Plaza, they lived in a motel for five days as they continued their search. They spent $275 on the motel, plus $380 in storage fees for their possessions, depleting their savings.

Agencies offering emergency housing assistance weren’t able to help with the security deposit on the new place they found at Sierra Point Apartments, but friends and family chipped in, Judy said.

“We passed the hat around and made it by the skin of our teeth,” Judy said. “It was a nail-biter, whether we were going to be out on the street, because we had exhausted everything at that point.”

Milton, who is now taking Pongratz to civil court to try to get back his security deposit, is adamant that tenants have rights and shouldn’t be afraid to defend themselves.

“I don’t care if you’re a felon, just stand up for your rights,” he said.

Joseph Chavez and Nadia Hill pause while packing to move. They gave up on an appeal of an eviction after Hill found out she was pregnant and they decided to join Chavez’s family in El Paso.

“BAD” TENANTS

Legal aid attorneys say that credible defenses can be overlooked by eviction court judges, even when tenants attempt to raise legitimate issues. Having an attorney at their side would help tenants articulate discrepancies that could lead to a dismissal — or at least a follow-up trial.

“Cases where there is a controversy should not be decided without testimony or evidence,” said Sabrina Fladness, housing attorney with Southern Arizona Legal Aid. “Something that’s so important to everyone — where you sleep, where you relax, where you love, fight — can be so easily lost in a process that doesn’t even have much published case law. ... It’s really hard to tell if our system is working.”

Nadia Hill, 31, knows she’s not a good tenant on paper. She now has multiple evictions on her record and a felony shoplifting conviction from late 2016, borne of desperation when a broken-down car prevented her from reaching her food-service job at Tucson International Airport. No buses ran early enough for her to make her 4 a.m. shift, and taking taxis every morning became too costly, she said.

After calling agencies like Interfaith Community Services and the Salvation Army and being told there wasn’t any financial assistance left for the month, “I reached a point of desperation and I made a stupid choice,” she said.

Nadia said she learned a lot from her first eviction, in which she withheld rent after her landlord failed to address plumbing issues, she said. Whenever she turned on the water anywhere in the apartment, “black sludge” backed up into the bathroom tub, she said.

But she did not give written notice before withholding rent, so she didn’t have a valid defense against the eviction. Nadia said that mistake, and the felony on her record, has limited her options ever since, pushing her into substandard housing.

In March 2017, Nadia and her boyfriend, Joseph Chavez, 34, moved into a $450-per-month condo owned by landlords Brian and Margeaux Bowers. The landlords were willing to overlook Nadia’s previous eviction, and they also allowed the couple to pay off their security deposit incrementally, Nadia said. The couple said they were struggling, but between Nadia’s job as a server and Joseph picking up handyman and construction work, they were getting by.

For the first couple of months, their rent payments had been a day or two late, but Bowers didn’t mention late fees until May 2017. The couple said they tried repeatedly to meet with Bowers to go over what exactly they owed.

“I said, ‘I’m willing to pay whatever late fees there are. Just tell me where they’re coming from,’ ” Nadia said.

When they finally met, Bowers couldn’t provide the specific breakdown as he didn’t have the right accounting book with him, Nadia said. But he accepted $75 from them and said he’d let them know if they owed anything else, the couple said.

Their next contact was a notice taped to their door on May 17, 2017, saying if Nadia didn’t pay $269 by 4 p.m. that day, Bowers would file an eviction action. On June 2, she received a more formal five-day “pay or quit” notice saying she now owed almost $800, including June rent.

Nadia said she had a $450 money order for the June rent ready to go. But she told Bowers she first needed a breakdown of what they owed to avoid being “harassed” for more unexplained charges, she said.

Before the judge in justice court on June 29, 2017, Nadia admitted that she hadn’t paid June rent, but she said she disagreed with the amount owed. On the day of her court hearing, she still had that $450 money order, but she didn’t have the chance to show it to the judge, she said.

The 12-minute hearing was tense and confusing. It included an argument over whether the landlord was aware Joseph was living with Nadia, the leaseholder, as well as controversy over whether Nadia’s name was forged on certain payment agreements.

Judge Newman focused on the inarguable fact that Nadia hadn’t paid rent for June.

“You admit that you owe for June ... so I don’t see your defense here,” Newman said. “I’m entering an order in favor of the plaintiff in this case, based on what you told me and what you admitted. I don’t have any choice in the matter.”

In an interview, Brian Bowers denied that he didn’t communicate what Nadia owed. He said he hasn’t received a dime of the $1,021 judgment he received against Nadia in Justice Court.

“I’m sure it’s convenient for them to tell you they don’t know how the amount got so high,” he said. He said some tenants intentionally bounce from place to place, seeing how long they can stay without paying rent.

“There’s people out there, their intent is to deceive landlords in order to stay there for free,” Bowers said. “The problem is not with the landlords. It’s with the tenants that don’t pay their rent. Rent is like any other bill — you have to pay it.”

Not paying June rent was a mistake on the tenant’s part, said attorney Daube, who wasn’t involved with the case.

Joseph Chavez hauls out the washing machine from the midtown-Tucson apartment unit he shares with girlfriend Nadia Hill (not pictured) on Sept. 7, 2018.

“A tenant should never give the impression that they are going on a rent strike for any reason, even a billing dispute with the landlord,” he said.

If Nadia had made the case in court that she offered to pay, and then focused on all of the factual disputes between her and the landlord, she may have secured a follow-up trial, in which she could call witnesses and cross-examine the landlord, he said.

Almost always, when tenants admit to the judge they haven’t paid rent, the reason doesn’t matter — with that confession, they’ve lost, Daube said.

“It was all about presentation,” he said. “She used the wrong words in court, and the judge locked on to those words as an admission.”

In retrospect, Nadia said, “If I’d understood that in court, they are not going to care that as tenants we’re getting harassed, I would have paid June rent and said, ‘I’m not paying a dime more in late fees or (unexplained) water bills until you give us a breakdown’” of what is owed.

Nadia appealed the eviction to Superior Court, writing in her July 5, 2017, memorandum: “There is no way the tenants could have known what to pay because the amounts constantly varied.”

Legal-aid attorneys who reviewed the case said there were some inconsistencies that a lawyer would have caught, which may have helped secure Nadia a follow-up trial. For example, the LLC listed as the plaintiff on the eviction paperwork is different than the LLC on Nadia’s lease, which Nadia pointed out in her appeal but did not raise at the hearing.

Plus, a lease wasn’t included in the records Bowers submitted to Justice Court, so the judge couldn’t know whether the amount owed was accurate.

Important documentation is commonly left out of eviction filings, said Ellen Katz, director of the William E. Morris Institute for Justice in Phoenix. She’s planning to file a petition with the Arizona Supreme Court to amend the rules of procedure for evictions, adding a requirement that landlords, when filing their eviction, must include a copy of the lease and an accounting of rent paid for the previous six months.

In August, more than a year after Nadia filed her appeal, the Pima County Superior Court mailed a letter saying Nadia owed $243 to proceed with the appeal and had 30 days to pay or petition for a fee waiver. The court initially sent the letter to the wrong address, and when Nadia finally got the letter, she had just days to file the fee-waiver paperwork. By that time, she’d found out she was pregnant, and she and Joseph were planning a move to El Paso, where Joseph has relatives. Nadia said she’s decided to give up on the appeal, but she’s angry.

“Our system is built to protect owners,” she said. “There’s no one to protect us.”