NOGALES, Sonora — Their jobs disappeared two years ago, but still they come to work.

No one pays them a salary anymore, but a Mexican arbiter granted them access to the factory where they used to work, along with possession of its contents. Every weekday they sit at the entrance to the now-silent inkjet cartridge remanufacturing plant, hoping someone will show up to buy the remaining gallons of ink or maybe some stray office furniture.

The factory’s former workers are trying to sell anything and everything in order to help them get the more than $1 million in severance pay — including lost wages — they say they were shorted after Denver-based Legacy Imaging abruptly closed its doors one weekend in February 2013 and left more than 100 people without jobs.

The building is dark, its lights off in an attempt to save every last peso for the workers. They flip the switch only when a paying customer wants to go inside and see the merchandise.

A sign on the wall wishes a ¡Feliz Navidad y Prospero 2013! But prosperity is long gone from the factory.

“It’s mentally draining to come and not know if there’s going to be a sale or not, but we are interested in getting paid what is ours,” says Karina Leyva, at 27 the youngest member and the only female leader of this quiet rebellion. “Perhaps it won’t be all of it, because we are talking about a lot of money. But at least some of it.”

That’s about all the workers hope for these days. Their quest has labeled them troublemakers, making it hard to land new work. Some are near retirement, so taking lower-paying jobs would hurt their future pensions.

Over their months of struggle, they have seen their numbers dwindle as attention to their cause faded and more of them took new jobs, even at lower wages.

They are losing faith that they will ever find the justice they seek.

“SWALLOWS” TAKE FLIGHT

It is illegal in Mexico to close a plant without providing severance and compensation pay to employees. But in reality, consequences are few.

Many companies close according to the law, but the practice of businesses taking flight is common enough that it has a name: Golondrinas. Swallows.

One company skips town in Sonora roughly every year, a university professor in Hermosillo estimates. In Nogales, it has happened at least four times since 2013, leaving about 600 workers without severance pay totaling potentially millions of dollars.

Mexico has no unemployment benefits, so in many cases workers terminated through no fault of their own are entitled to three months of salary, 12 paid days for each year they worked for the company, and any outstanding vacation and Christmas bonus money. And the clock keeps running for up to a year while a legal case proceeds.

A quick Google search yields more than a dozen media reports of illegal shutdowns over the last 14 years affecting more than 5,000 workers throughout the country, from Juárez to Chiapas. But no entity, governmental or otherwise, tracks how often it happens or what share of companies that close do so according to the law, an Arizona Daily Star investigation found.

The issue is not specific to Mexico. It has happened in El Salvador, Guatemala and even Indonesia, where in 2011 the Maquila Solidarity Network reported that nearly 2,700 workers were left without jobs and owed $3.4 million in severance pay.

Among the ideas for change in Mexico and other countries: require companies to set aside funds when they start maquiladoras, or foreign-owned factories where goods are manufactured or assembled and then exported back to the original country. If the maquilas later close, that money would be used to secure workers’ compensation.

But such plans haven’t garnered enough support to be implemented — especially when more than half of the economies of Nogales and similar cities depend on manufacturing and when there’s increasing competition for their business.

For now, workers are left to fend for themselves, oftentimes facing off against powerful interests in a labor system that advocates say is rigged against them.

It is up to employees to recover what they can, including selling whatever the companies leave behind. That’s what the Legacy workers have been doing for nearly two years.

THE FACTORY CLOSES

On Feb. 5, 2013, workers arriving for their 7 a.m. shift at Legacy de México found a growing knot of people outside.

Someone had changed the locks, they figured. But a company manager, Rodolfo Moreno, soon arrived and said the plant had closed. He offered them a month’s salary — far less than what they were legally owed.

“From the moment the company closes without saying a thing,” says Rigoberto Dorame Felix, who earned roughly $37 a day as the head of maintenance, “that’s to hurt you, not to help you.”

For Aureliano Flores, 61, it was déjà vu. The same thing happened to him in the mid-1970s, when he was a newlywed. The difference, he says, is that back then there was more work available and he was young: Within seven months he had a new job.

To prevent the owners from removing machinery while they sorted out the dispute, Legacy employees stayed put outside the factory. Under blue and black tarps, in groups of five or six, they watched the building around the clock. They used a small camping stove to heat water for coffee, which they offered to visitors, including the mayor of Nogales, the governor of Sonora, federal lawmakers and charities interested in helping.

The women cooked corn, soup, potatoes — anything to keep them warm. In February, the average high temperature in Nogales is 67 degrees, but the low is 31.

They spent 143 days under that canopy.

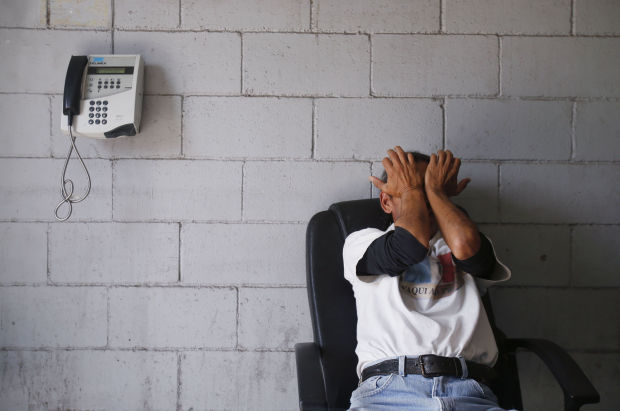

“I was so enraged that I couldn’t sleep,” remembers Dorame Felix, 55. “They left us with nothing for our families and there was nothing I could do.” The mediation council estimated in March 2013 he was owed about $7,000 not including lost wages. Adding in a year of lost wages adds another $14,000 at current exchange rates.

His family’s sole income comes from his wife’s job at another maquila and what he makes at odd jobs. Sometimes he doesn’t even have enough money to add call time to his cellphone.

He used to give his 14-year-old twins $65 to $95 a week for food and whatever else they needed, but “that all ended in one fell swoop,” he says.

That he can no longer support the boys, who live with their mother, is what hurts most.

“They call me and ask for money. Where am I going to get money to give them?” he asks. “I’ve let them down.”

TAKING POSSESSION

The day workers learned that Legacy had closed, a group of them went to the local mediation council, which helps workers and employers negotiate labor disputes, and filed a lawsuit against the corporation seeking wages and severance pay. About a quarter of the plant’s 113 workers who joined the suit had worked there 10 years or more.

Company representatives did not show up for a hearing, so in March 2013 the workers were granted possession of everything inside the building. On June 27, they got the keys and were able to set up shop inside.

But they were unable to convince the arbiter that three production lines and finished material they estimated to be worth $300,000 had been removed before the company shut down and illegally sold or given to a competitor. (For more details, see accompanying story.)

The workers are still considering their legal recourse. They thought about suing U.S. Legacy owner Frank Day, but they can’t go after him personally or his assets unless they can prove fraud or mismanagement, says Carlos Sugich, partner at Snell & Wilmer, a Phoenix-based business law firm.

Legacy Imaging in Colorado dissolved in November 2013. There are no bank accounts or assets to pursue.

A cross-border lawsuit, Sugich says, is costly and drawn out.

LEADING THE CHARGE

Former Legacy workers chose three of their own to lead their charge.

Aureliano Flores is the patriarch of this new family. He’s the spokesman when reporters seek an interview or when a church group from across the border wants to learn what happened.

He started working for Legacy two years after it opened in 1996, and by the time it closed he coordinated training as well as shipping and handling, earning nearly $30 a day. He was his family’s breadwinner and a year from retiring with full benefits when the plant shut down.

“One had some sort of stability, an income, and all of a sudden that stability ends,” Flores says. “It’s very hard because the bills keep coming.”

The labor mediation council estimated he was owed about $7,000 plus lost wages, which adds another roughly $10,000 a year.

Rigoberto Dorame Felix worked for Legacy since 1999. He’s handy and knows many of Legacy’s operations — he even helped build some of the machinery used in the factory.

Karina Leyva started work as a human resources assistant two years before Legacy closed. She earned about $15 a day. She’s usually soft-spoken, but as soon as she starts talking about the case, she’s sharp, confident and to the point.

She has applied for several jobs since Legacy shut down. But during interviews, she says, hiring managers mention her involvement in getting the workers back pay and suggest she apply at another time.

“They think that because you know your rights already you are going to mean trouble for them later on,” she says.

She lives with her parents and helps out in her family’s small convenience store. That eases some of the financial pressure like that her former co-workers face, but she doesn’t know how much longer she can keep it up.

It takes her nearly two hours on two city buses to get to and from the factory. Most days she tries to reach the attorneys in Hermosillo or takes a bus to the mediation council downtown to get copies or follow up on the case. She often can be found sitting in her former office or in the cafeteria, a calculator and pen in hand, scratching notes in her green notebook with a big red heart on the front.

If the company owner could see them, Flores says, “he would realize the great damage he’s done to us.”

The Arizona Daily Star tried to reach Legacy owner Day, a restaurateur from Colorado, and chief executive officer Michael Frothingham, now president and CEO of ColorLabs Ink Innovations in Pennsylvania. Neither responded to two emails each or to three calls to Day’s home and three calls to Frothingham’s home and office. (For more details about Day and his operations, see story on previous page.)

PASSING THE TIME

Legacy’s Nogales factory, roughly half the size of a football field, is full of old printers, ink cartridges and office equipment. Everything is potential cash: brooms, cisterns, desks, chairs.

Trinidad Vargas, or “Trini” as he’s called by his colleagues, is 62 and admits there are days when he doesn’t want to take the bus to go to the factory.

“It’s tedious to be here every day,” he says. “But you can’t let those who wronged us get away with it.”

Most of the time workers sit by the plant entrance in old executive office chairs.

They bought a generator that could run the lights, but diesel is pricey, so running it costs about $7 a day. Now they use a flashlight to find cartridges or dismantle 16-foot racks and tables.

Most days there’s not much to do. They play dominoes and read the local newspapers. They sweep the floors, take out the trash and tinker with outdated printers to see if they can get them to work.

“We used to only talk,” Flores says, “but we got tired of looking at each other’s faces.”

They set up a system to harvest rainwater, which they store in large plastic bins, to use for the bathrooms and to wash their hands.

In the winter the building is as cold as an icebox and workers wear heavy jackets inside. In the summer after a monsoon rain, mosquitoes swarm and bite workers, even through their clothes.

Business has been slow. They’ve sold about 600,000 pesos, or $40,000, worth of items in nearly two years, not enough to cover even 10 percent of their severance pay.

Occasionally clients trickle in. Most hear about them in the news or through word of mouth.

“I’m looking for a desk,” a woman says one recent day. Juan Pacheco, 50, grabs a flashlight and directs her to the back. That’s where the executive offices used to be; now all that’s left is some dusty desks.

Another woman negotiates for the cafeteria tables. She takes eight for less than $50 each — half the workers’ asking price.

When customers want ink, Pacheco cleans water bottles and carefully pours in colorful liquid from tall, heavy plastic jugs. A half-liter bottle of ink sells for less than $7. The retail price would be about $30.

“I even filled up a little more,” he tells a customer as he loads the bottles into a box.

Pacheco started as a line operator at Legacy in 2007, earning about $6 a day. Now he plays his guitar for tips at restaurants and on buses. He waits tables when he’s asked and collects aluminum cans on the weekends.

Victor Valverde Romero, 52, worked for the company for 15 years and earned $28 a day as a production supervisor.

He still shows up daily, sometimes donning a navy-blue coat with the Legacy emblem on the side while he’s cleaning or dismantling equipment. When the factory shut down, he was about 10 years from retirement and had big plans, including building apartments on property he owns.

“You start adding up how much money you are going to get when you retire,” he says, “when all of the sudden all your plans come tumbling down.”

OPTIONS ARE WANING

As the months go by, workers feel their options running out.

Soon they must decide: How much further are they willing to go? How many more days can they sit and wait for a client to walk in?

They know their chances are not good. But giving up means accepting defeat, starting over. That’s not something they’re ready for.

Still, their passion is fading. Some of them no longer show up right at 9 a.m. Others don’t come every day.

They had hoped the mediation council would rule in their favor and make the competitor who bought some of the equipment from Legacy return it so they could sell it. That didn’t happen.

They had hoped their attorneys would be willing to go all the way, even if that meant an international lawsuit. That doesn’t seem likely anymore.

One of the workers, endearingly referred to as Doña Ana, had pledged to fight until the end. She died more than a year ago.

They’ve already spent thousands of dollars since their battle began more than two years ago: $65 for a copy of their legal case — the equivalent of two weeks of work at minimum wage — $7 every two months on cleaning supplies, $1,000 on trips to Hermosillo to see lawyers, and more than $2,000 reimbursing their attorneys for travel and food expenses.

Flores, the spokesman for the workers, tries to remain hopeful, to keep the faith.

“Every morning when I leave my house, I entrust myself to God,” he says. “I ask him for something different to happen, something for this situation to change.”