A group of about 40 students gathered outside a San Luis building — where many who came decades before them had organized alongside civil-rights leader César Chávez.

They called for family reunifications at a time this summer when a government policy had resulted in more than 2,500 immigrant children being separated from their parents at the border.

“What was done is not fair,” then San Luis Mayor Gerardo Sanchez, a Democrat, told the group in Spanish. “You march today to stop these injustices.”

That same day, about 20 miles north in a more conservative Yuma, members of the Immaculate Conception Parish held their first forum aimed at dispelling rumors that their refugee ministry was harboring unauthorized immigrants.

President Trump won in Yuma County with 50.5 percent of the vote in 2016. But in southernmost parts of the county such as San Luis, Democrat Hillary Clinton took nearly 90 percent.

For decades, immigration has been a highly politicized and divisive issue, especially around election time. A Pew Research Center poll before the 2018 midterm elections found that 75 percent of GOP voters said illegal immigration is a “very big” problem in the country today, while just 19 percent of Democratic voters said the same.

And while nearly 6 in 10 Democratic voters said the way unauthorized immigrants are treated is a very big problem, just 15 percent of Republican voters said this.

Fears about a border “invasion” need to be listened to, says former Bishop Gerald Kicanas. “But also people need to get more information, need to get more understanding.”

Forum organizers were well aware of the fraught territory in which they were treading.

“We hope to go through this meeting in a respectful way and find the best ways to see each other as brothers and sisters,” Father Manuel Fragoso told the 200 or so attendees.

They wanted the conversation to be about the families they worked with and the role of the church, not a platform to discuss general immigration topics or to attack a specific administration.

They made sure the U.S. flag was visible, setting it up on stage next to the speakers, and invited former Bishop Gerald Kicanas of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson to help lead the conversation.

“The world is on the move today,” Kicanas told the crowd. “This is something the whole world is facing today, not only we here in the United States.”

He referred to the families as refugees and emphasized how the church was helping the government by making sure the immigrants got to where they needed to go; it wasn’t sanctuary.

Over the last few years, the church had taken over spearheading a small ministry that temporarily cared for families released by the government with a notice to appear later before an official.

Several years ago, residents started spotting migrants dropped off by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers by a local Walmart. They would wander, without knowing what to do or where to catch a bus to cities across the country. Yuma doesn’t have a Greyhound bus station, only a stop by a shopping center.

This led to the creation of an interfaith ministry to provide these families a temporary place to rest, eat, shower and connect with their families or friends elsewhere. Eventually the Yuma Refugee Ministry was born.

But organizers tried to keep it pretty much out of the public’s view, fearing anti-immigrant backlash. People had called the police on the church where the families were housed. Others had shown up to scream at the guests, and volunteers wanted to protect them.

That in turn led to rumors about what the church was or wasn’t doing — including that they were picking up people off the street who were illegally in the country.

The coordinators wanted to clear the air. The number of people arriving at the border was steady, after dropping off briefly after President Trump was elected, and they needed a constant flow of volunteers and donations.

They invited experts to discuss conditions in Central America. Kim Curtis, a Northern Arizona University professor, talked about the country’s moral obligation to this region.

Father Manuel Fragoso listens to speaker Kimberly Curtis during a forum aimed at dispelling rumors that a Yuma church ministry is harboring unauthorized immigrants.

It was important to remember the role the United States played in military interventions and in its support of brutal dictators, she said, which in the case of Guatemala led to a 36-year civil war that resulted in more than 200,000 dead and over a million displaced. President Clinton had apologized to the Guatemalan people, she told attendees.

“When history is erased, people’s moral values are also erased,” she said. “If you think they are invading our country, we have to think of this history and ask ourselves where responsibility lies.”

Suzannah Maclay, a Phoenix immigration attorney, talked about the asylum system. The reality was that many of those coming through Yuma would ultimately be denied asylum, she said, especially after the Trump administration further narrowed the definition of who could potentially qualify, excluding victims of domestic or gang violence.

If anything, she said, the issue is about how the legal system can accommodate the shifting demographics.

In the end, there’s a need to work to try to address the reasons people are coming, Kicanas told attendees.

“The more we can understand, work with other countries to improve their situations,” he said, “the less they will be required, or forced, to leave their homes to find some semblance of dignity or respect.”

Mary Eritch read about the meeting in a local newspaper and wanted to know more about it. “When you don’t know, people are afraid. What is your moral responsibility in your own community? I’m for it,” she said, echoing the sentiment of several attendees a Star reporter spoke with.

Steve Miller, a longtime Yuma resident, knew about the rumors and was glad to hear them dispelled.

“I’m Catholic,” he said, and based on those teachings, “we are supposed to help, but (while) following the law.”

ICE now transports migrant families from Yuma to Phoenix and Tucson — cities with more capacity to assist. As a result, the Yuma Refugee Ministry is no longer active. Above, the ministry’s Connor Veneski is shown moderating a July discussion.

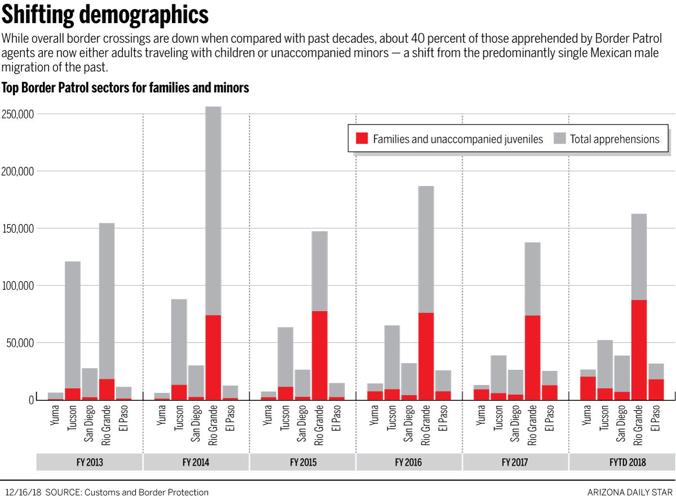

He experienced a time in Yuma when Border Patrol agents made more than 100,000 apprehensions a year. He believes the fence helped stop some of that traffic and the drugs coming through — and thinks it can work elsewhere.

“I look forward to Trump building his wall just to keep the drugs out of our country,” he said, “and I look forward to his gates, as he says he wants to put up, to let the good people through.”

Since the president took office, in some ways the “gate” has gotten narrower after cuts in the number of refugees admitted into the U.S., travel bans for certain countries, ending temporary protective status for more than 300,000 others, and an attempt to exclude those who cross the border illegally, including children, from being able to seek asylum.

Living in Yuma, also known as the lettuce capital of the world, Miller recognizes farmers need workers. He would like to see a functioning visa system and comprehensive immigration reform, he said, and for elected officials to “get off their hands and actually do their job and not care whether they are ‘R’ or ‘D.’”

In October, ICE released hundreds of families into Southern Arizona, which prompted Yuma’s mayor, Republican Douglas Nicholls, to reach out to Arizona’s congressional delegation, saying it was overwhelming the ministry and the community.

“We had a lot of people engaged in helping the 275 who did come through the city, which speaks volumes on what the humanitarian side is,” Nicholls said. “The issue is really the immigration system itself not working correctly ... and it can’t be solved locally.”

Yuma doesn’t have a Greyhound bus station. Here, the Chilel and Ruiz families, new arrivals from Central America headed for destinations east, wait for a bus in a Target parking lot.

Sen. Jon Kyl pressed Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen for answers during a Senate hearing a few days later, saying Yuma had been overburdened as the numbers of people were “flooding into the community without an ability to do anything about it.” Yuma has a population of 95,000.

Later that month, Kyl and Jeff Flake, sent a letter to Nielsen asking, among other things, how the federal government could help places such as Yuma financially and to develop a plan to “assist their constituents with public safety and humanitarian risks posed by large-scale releases of migrant family units.”

The Yuma Refugee Ministry has since been suspended. ICE now transports families to Phoenix and Tucson, cities with greater capacity.

But while the ministry is no longer in action, its existence and the message from the church illustrate the balancing act that many organizations helping migrants are having across the country, especially in more rural communities.

“There’s a great deal today about an invasion or somehow that our country is going to lose our culture, or we won’t have our needs attended to,” Kicanas said during the summer forum. “Fears that need to be listened to, need to be understood, but also people need to get more information, need to get more understanding of the situation.”