Thousands of parents and their children continue to make the journey north — they either wait in line for days or weeks outside ports of entry or cross paths with Border Patrol agents and seek refuge.

The growing numbers have been particularly troublesome to President Trump, who’s made cracking down on immigration central to his campaigns and administration. He’s continued his calls for a wall; instituted a policy that led to the separation of more than 2,500 children from their parents; and deployed thousands of troops to the border.

But that hasn’t stopped many of the families and minors who are fleeing gangs, extortion and violent partners. Nor those escaping poverty, wanting to reunite with relatives or in search of a better job. To the contrary, thousands keep coming, increasingly in large groups.

How do you secure the border when half of those arriving borderwide — and more than three-fourths of those arriving in the Border Patrol's Yuma Sector — are not trying to evade law enforcement nor the walls built to keep them out?

Most of the migrants arriving in southwestern Arizona make no attempt to escape detection and simply turn themselves in. Above, Denilson Agustin waits at a Yuma shelter with his mother, Marleni, who wears a monitoring bracelet. She has agreed to show up for an immigration hearing.

Waiting to cross

Temperatures soared to 117 degrees in late July as a small group of migrants waited on the sidewalk leading up to the San Luis Port of Entry, south of Yuma.

Marleni Aguilon, a 23-year-old mother from Guatemala, clutched her baby, Denilson, close to her chest between breastfeeding and pouring water over his head to cool him down.

She wanted to ask for refuge, but for the last seven days officials had told her to come back tomorrow.

“They say they have no space for us,” she said, her voice cracking.

While there are those like Aguilon who wait outside the port of entry, getting into the U.S. from the small Sonoran town can be as easy as climbing a tree and clearing the older landing mat fence into San Luis, Arizona. (The government plans to replace 14 miles of it at a cost of $172 million, starting next April.)

Others head west to an area where all they have to do is walk around a tall pedestrian fence that runs close to a canal.

Either way, they wait. They know eventually a border agent will show up to pick them up.

The border fence comes to an abrupt end at the dry Colorado River west of San Luis Rio Colorado, Sonora.

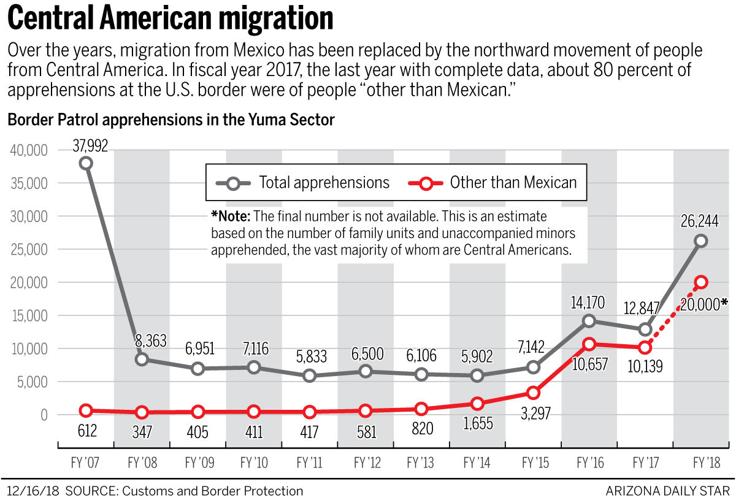

With the exception of the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, the shift in demographics of those coming is perhaps nowhere more visible than here. The Yuma Border Patrol Sector has become the second busiest when it comes to arrests of family units and unaccompanied minors, which in fiscal year 2018 represented three-fourths of all arrests — higher than the national average. And in October, the first month of this fiscal year, their share of all apprehensions in the sector climbed to 85 percent.

That doesn’t include those such as Aguilon. The number of parents and their children who presented themselves at Arizona ports of entry jumped from 2,634 in fiscal year 2016 to 10,428 last year.

Government officials tell migrants that if they want to seek asylum they need to do it the right way, at an official crossing. But at least since this summer, the time families have had to wait to be let in has gotten longer, with officials telling them they don’t have space to process them. This in turn has led some to cross illegally to turn themselves in.

That day in late July, San Luis port officers called over the group of migrants, who had been waiting for days, when they saw them talking with Arizona Daily Star reporters. They allowed half of them in, including Aguilon, and told the rest to come back in a few hours.

Once inside, officers wanted to know what the reporters asked, and questioned the veracity of the migrants' stories.

“They kept saying ‘you are coming with a guide, how much did you pay?’ They said I was telling lies because I told them I didn’t know my husband’s whereabouts,” Aguilon said, “but what else did they want me to say if I was telling the truth?”

The Star found Aguilon two days later at a Yuma church that served as a type of temporary shelter for those being released by immigration officials. After processing them, which includes taking biographical information and a cursory background check, Immigration and Customs Enforcement brought migrants here so volunteers could help them contact relatives elsewhere in the country.

Aguilon was released with a piece of paper telling her to appear before an immigration official, and with a monitoring ankle bracelet strapped to her foot.

She had two weeks to make that appointment in Alabama, where a brother-in-law expected her.

Migrants from Central America and Mexico talk with Customs and Border Protection officers, trying to get admitted for asylum interviews at the San Luis Port of Entry southwest of Yuma.

A shining example

Until recently, Yuma was the prime example of what a secured border looked like.

It became the “proof of concept” that the border could be protected and controlled, said Ron Colburn, Yuma’s former sector chief, who eventually became national deputy chief of the Border Patrol.

It showed what a combination of fencing — a triple layer in some places — manpower and a zero-tolerance prosecution policy could achieve: arrests went from nearly 140,000 in fiscal year 2005 to about 8,300 by 2008.

Before any of that was in place, dozens stormed the border, with agents outnumbered 50-to-1, according to a 2009 Border Patrol “Securing Yuma Sector” video that showcased the sector’s success.

Apprehensions sometimes exceeded 800 per day. Only 12 of the 126 miles of the sector were fenced.

In 2005, there were more than 2,700 vehicles drive-throughs loaded with people or drugs. Colburn estimates there were a couple hundred thousand “got-aways,” border crossers who agents didn’t catch.

There were also bandits preying on migrants, and smugglers who assaulted agents. In 2008, Border Patrol agent Luis Aguilar was run over and killed by a suspected drug smuggler.

“There were areas we didn’t control, we couldn’t tell where was Mexico and where was the U.S.,” Border Patrol agent Justin Kallinger said during a July ride-along.

“We wouldn’t have come here,” he said, as his colleague parked a Border Patrol SUV by the floating fence — seven miles of steel barriers that shift with the sand — in the Imperial Sand Dunes. “It was no man’s land."

Between 2004 and 2009, the number of Border Patrol agents in the sector almost tripled, from 330 to 930.

About 900 members of the National Guard were deployed and helped build new fences: 13 miles of vehicle fence and access gates along the Colorado River; nine miles of secondary fence and lighting near the San Luis Port of Entry; 68 miles of vehicle and pedestrian fence across the Sonoran Desert.

At the same time, Yuma became the second sector to adopt a policy aimed at prosecuting as close to 100 percent of border crossers as possible to serve as a deterrence.

All of this led to a decrease in apprehensions, officials say. There were hardly any drive- throughs. Instead of the large groups that at times exceeded 100 migrants, smugglers tried to get across a handful at a time to avoid detection.

Traffic along the Arizona border didn’t end, though. The Tucson Border Patrol Sector, which became the busiest in 1998 as traffic shifted from El Paso and San Diego, continued to apprehend hundreds of thousands of people a year.

Tougher border enforcement also meant that the typical Mexican male migrant was not crossing back and forth anymore, instead choosing to avoid the risk and build a life in the United States. Increasingly, those apprehended became Central American single adults, then families — each shift in response to the changing environment.

Many choose the Rio Grande Valley, a much more direct route, making it the busiest crossing in 2013.

Some of that traffic is making its way back to Yuma in the form of families and unaccompanied minors, although it still pales in comparison, not only to the family and juvenile apprehensions in the Rio Grande Valley — 87,035 in fiscal year 2018 — but to Yuma’s overall peak years.

Now, they don't run

Agents are apprehending large groups again, but now the groups don’t run, they just sit and wait.

Instead of agents focusing on criminals, Colburn said, now they have to spend their time processing and tending to humanitarian needs. Last month, 50 Border Patrol agents from other sectors were sent to Yuma to help.

Recent news releases from the sector highlight this trend:

- Sept. 17: Agents said they apprehended 275 adults and children, 20 of whom were treated at a hospital for back and ankle injuries, lacerations, lice and contagious skin infections.

- Nov. 9: Agents in the Yuma station reported the arrest of 449 people, the vast majority Central American families.

- Nov. 14: Over the course of two days, Yuma Border Patrol agents apprehended 654 people. Most were Guatemalan family units and unaccompanied minors who surrendered near shallow portions of the Colorado River.

It’s part of the ever-changing landscape and agents always adapt, Kallinger said.

Regardless, they must never let their guard down, said Border Patrol agent Jose Garibay.

“We’ve encountered cases where they pretended to have parental relationship to a child using fraudulent documents,” he said of some migrants.

In June, a Guatemalan man crossed the border illegally in the Yuma Sector with his supposedly 15-year-old daughter. The birth certificate they showed was fake. The man was her brother-in-law and the girl was 18. Both were prosecuted and pleaded guilty to making false statements to the government.

Between April 19, when the agency started to track these cases, and Sept. 30, officers separated 170 supposed families nationwide after determining people were unrelated. Another 87 were separated because the minors were over 18 years old, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

And, "just because you are getting a lot of these family units doesn’t mean the other traffic is not crossing as well,” Kallinger said.

Yuma agents still catch groups smuggled through checkpoints, or criminals, such as a 57-year-old Mexican man convicted of rape, arrested twice in five months.

In August, they found a cross-border drug tunnel that went from a home in Mexico to an abandoned fast-food restaurant in San Luis, Arizona.

And more recently, a 31-year-old Honduran, who claimed he was part of the migrant caravan, climbed a tree, set it on fire, and began to throw rocks to avoid arrest.

Still, agents’ days are mostly consumed by picking up and transporting Guatemalan parents and their children before turning them over to ICE.

Melanie Gayana plays with the toys she’s carefully collected at the Yuma Refugee Ministry’s one-room shelter, Saturday, July 27, 2018, Yuma, Ariz.

A long journey

Melanie, age 9, crossed the border with her father this summer. She is not sure where; she just remembers it was by the fence and there was a gate a Border Patrol agent opened for them.

It had been eight days since they left their Guatemalan village and traveled through Mexico on a bus. The journey had taken its toll on the child.

Along the way she was overcome by sadness, she said, and when her dad called her mother to comfort her, she struggled to get the words out.

“I could only say that I missed her,” Melanie said. “The feelings were overwhelming.”

She even missed her 3-year-old brother who was always annoying her, she said, speaking as she neatly arranged stuffed animals on top of a blanket inside the Yuma church. She already had her favorites: the light blue bunny and the white horse with roses.

In Guatemala she didn’t have toys. “I used pieces of paper to pretend I was at a bank or a health clinic.” She loves the sound the pages make, she said, flipping through a Mickey Mouse book she had colored carefully.

It wasn’t their first choice to come to the United States, her father Juan Carlos del Valle said, as he washed dishes at the Yuma Refugee Ministry. At the ministry they could rest for a couple of days until they got their bus tickets to go to Florida to meet relatives.

“Only God knows the needs of each family,” he said. There’s no work in Guatemala and the lack of rains have meant fields are not producing enough, not even to eat, he said.

“If you are lucky and you make 50 quetzales a day, roughly $6.50,” he said. “A kilo of sugar is 8 quetzales, a kilo of beans is another 10; three bars of soap is 18 and sometimes you only work two or three days. Other times, there are weeks that go by without work.”

“This trip is not for pleasure,” he said. “I felt a knot in my heart when it was time to say goodbye to my wife. I told her she had to be brave.”

He said he will follow the law and if the judge decides he has to go back, he will leave.

Yuma Refugee Ministry volunteer Fernie Quiroz bids farewell to Ana Pascual and her daughter Kimberly as they get set to board a bus for the East Coast. Fearing anti-immigrant backlash, the ministry has largely tried to operate out of public view.

Why Central American migration changed

Those who come heard stories back home — either from the smugglers, or from others from their villages who made it and are still here — that they have a better chance of avoiding immediate deportation if they are processed with children.

Often they have relatives, close friends or even spouses they are hoping to reunite with and who tell them they have jobs ready for them in the United States.

Migration from Central America has not always existed the way it does now, though. Researchers point to the upsurge in violence that followed U.S. political and military interventions in the region during the 1980s.

“The result was a brutal civil conflict that took hundreds of thousands of lives, hobbled the economies of the nations involved, and displaced hundreds of thousands of people northward toward the United States,” Princeton University sociologist Douglas Massey has written.

Although the political violence that originally drove Hondurans, Salvadorans and Guatemalans north wound down during the 1990s, it was replaced, he said, by gang violence, continued economic turmoil and the increasing familial ties between Central America and the U.S.

“Central American apprehensions are rising as the sons and daughters, nieces, and nephews of undocumented migrants who left during the 1980s seek either to reunite with family members in the U.S. or to escape gang violence and economic turmoil at home,” Massey said.

In 1979, only 10,545 immigrants from Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras entered the United States. The number grew to 24,381 in 1988 and surged to 136,062 in 1990, according to Massey's research.

In fiscal year 2017, the Border Patrol made more than 160,000 apprehensions of Central Americans.

By 2015, the Central American unauthorized population in the U.S. had risen to about 1.5 million, most of whom maintained ties to relatives in their home communities, which Massey said facilitates future migration.

Marleni Aguilon, who presented herself at the port of entry, said she fled from her indigenous community because of violence.

“Some men with their faces covered had come in and beat my dad and sent him to the hospital and were demanding money from us,” she said, “so my husband and I fled with our two kids.”

According to Aguilon, they got separated in the hills as they tried to hide. She said she asked for help in Mexico but was sent back. She tried crossing again and made her way to San Luis Río Colorado, but she hadn’t heard about her husband.

Just before midnight on Tuesday, Oct. 2, Yuma Station agents apprehended a group of 108 parents with their children who surrendered half-a-mile west of the San Luis Port of Entry. Five hours later, agents arrested another group of 58 who crossed about one mile east of the port of entry. The vast majority were Guatemalans and included 88 children.

Claims of loopholes and frivolous asylum cases

One day in October, the Border Patrol’s surveillance cameras captured a group of 108 people agents said smugglers dropped off at the border fence in four places simultaneously.

Out of those, 100 were Guatemalans and included nine infants and toddlers from 1 to 5 years old, along with 43 other children.

The Trump administration says many of these parents are taking advantage of what it considers loopholes. The only answer to this problem, administration officials say, is to detain these families until their cases go through the process.

As it stands now, the government doesn’t have the capacity to hold the number of families arriving monthly — ICE has roughly 3,300 beds in family detention centers in Texas and Pennsylvania — nor the legal authorization to hold children beyond 20 days.

The Obama administration also tried to expand family detention as a way to deter and handle the rising number of families. But in 2015, a federal judge ruled that detaining children for long periods in that type of facility, even with their parents, was a violation of the Flores Agreement, which calls for children to be released to a parent, legal guardian or close adult relative. If that's not immediately possible, children must be placed in the least restrictive setting appropriate to their age and needs.

What ends up happening with many of the families who arrive in Arizona is that they are vetted and released with a notice to appear before an immigration official at their final destination, usually a place where they have a close friend or relative who can sponsor them.

There, they continue to check in with ICE and eventually get an appointment before an immigration judge where they can seek legal relief, including asylum, but that may take years. There are currently more than a million cases pending before immigration judges across the country.

"This well-known loophole acts a magnet for family units and entices smugglers to use children as a way to gain access to the United States by posing as a family unit," said Katie Waldman, a DHS spokeswoman.

The administration argues migrants know that if they come with a child they will likely be released and that it may be a while before they see an immigration judge, so they don’t have an incentive to comply, especially if they don’t have a strong asylum claim.

Currently about 80 percent pass what is called a credible-fear interview, the first hurdle to winning asylum. But only about 20 percent of Central Americans' were granted between 2012 and 2017, data from Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse show — a percentage that's even lower for those without legal representation.

The administration says that proves most claims are frivolous.

Attorneys and immigrant advocates say the low approval rate is a reflection of the complexities of asylum law and the fact that the vast majority don’t have legal representation.

Trump administration's strategies

In an attempt to curb the rising numbers, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued new legal guidance in June that largely eliminates domestic abuse and gang violence as grounds for asylum.

Under current asylum law, a person must show they face persecution in their home country because of their race, nationality, religion, ethnicity or social group.

The administration has also called for an end to court protections for children taken into custody at the border. It has talked about giving parents the option to remain detained together with their children or be separated while their cases proceed. And tried to ban those who enter the country illegally from seeking asylum, a policy temporarily blocked by a judge.

Trump has continued to call for a wall, threatening a government shutdown if it isn't funded.

The government also deployed nearly 6,000 troops, in addition to the 2,000 National Guard members already at the border, to prepare for the arrival of thousands of Central Americans who started making their way north in October, a migration the administration has called an "invasion."

Retired CBP Commissioner Gil Kerlikowske, who served in the Obama administration between 2014 and 2017, is among critics who called the deployment a political stunt.

“The deployment of active duty military and setting up concertina wire made very little sense when you are talking about these kinds of numbers,” he said.

In 2000, the Border Patrol made 1.6 million apprehensions; last year it made below 400,000. "If you reduced cancer by that percentage you would be in Oslo getting the Nobel Peace Prize," Kerlikowske said. "CBP is clearly within their resources able to handle those numbers, that should be kept in mind.”

Randy Capps, director of research with the Migration Policy Institute, said, “It’s not a major migration crisis. We are still talking about tens of thousands, not hundreds of thousands and certainly not millions. It’s something we can handle as a nation of more than 300 million people.”

Guatemalan Ana Pascual and daughter Kimberly wait in a shopping mall parking lot in Yuma with a dozen other immigrants for a bus to the East Coast.

Policy proposals

To address the current situation — and that question of how to "secure" the border when many are simply turning themselves in — experts said there's a need to:

- Redirect border resources to ports of entry and processing of asylum-seekers, and to immigration courts;

- Crack down on U.S. employers who hire unauthorized workers;

- Pass comprehensive immigration reform that includes a functioning guest worker program to meet U.S. labor demands;

- Address the root causes of migration through foreign policy and investment in Central America.

With the demographics changing of those who are coming, the line separating economic migrants from those in need of humanitarian protection has gotten blurrier, said Capps, of the Migration Policy Institute.

“It’s not easy to determine because there are several factors at play: extreme poverty, drought and climate change, violence, government instability — a combination of things that aren’t easy to differentiate,” he said.

“When you have most people coming from those places instead of being pure economic migrants, which was the case for most decades for Mexicans, you need to shore up the infrastructure that can make those determinations,” he added.

“You don’t need a wall, you don’t need more Border Patrol agents, more sensors, helicopters or drones or blimps. … You need people who can talk to the migrants and determine in a systemic, fair, humane and just, but also balanced way, who deserves asylum and who doesn’t," Capps said. “If you hand someone a piece of paper to show up at a court date years in the future, that’s not the best way to do it.”

Asylum requests are about 30 percent of pending cases before immigration judges, the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute wrote in a recent report about what it called an "asylum system in crisis."

While the administration has added some judges and asylum officers, that hasn’t put a dent in the backlog, researchers found.

Existing laws and policies are less well equipped to meet the humanitarian and enforcement demands associated with these newer cases, the Department of Homeland Security's Office of Immigration Statistics said in an August 2018 report.

For instance, 92 percent of single Mexican adults apprehended in 2014 were sent home by the end of 2017. But only 3 percent of non-Mexican unaccompanied minors; 10 percent of family units; and 33 percent of asylum-seekers (whose claims were denied) detained in 2014 had been returned by the end of 2017. Of those that remained, most had their cases pending.

"The problem," said Capps, "is that for a majority of these families it's taking three or more years for their cases to go through the system as it is and that’s a long time. It’s like having a temporary permit to stay in the U.S. and that’s how it’s being sold."

Not everyone will have a valid claim, he said, but if their cases are adjudicated much more quickly and fairly, “you would stop sending a signal that your future is uncertain in the U.S. but at least for a while you are going to be OK." Otherwise, he said, "people are willing to take those odds."

And because motivations for family reunification only increase with time spent apart, it is likely that migration by young Central Americans will continue, Massey, the sociologist, predicts.

This rise in migration from the Northern Triangle region — Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador — also comes at a time of a record low unemployment rate in the U.S. and more than 7 million job openings, which has historically been a strong "pull" factor.

"The economy could be a draw for this group (Central American families), but if they didn't think they could get through and be here for a time," Capps said, "they wouldn't take a chance."

"If you want border security," said Colburn, the former national deputy chief of the Border Patrol, "it's not just a linear environment between two countries, it's also policy and what goes on domestically in the country.

"So employer sanctions are important to defeat the draw," to penalize U.S. employers who hire unauthorized workers, Colburn said.

The E-verify program allows employers to verify the legal status of their employees, but only a handful of states mandate it for all new hires — Arizona among them. For the rest it is primarily voluntary.

Its enforcement is not rigorous. For instance, in Arizona, only 59 percent of new hires were checked against federal records in the second quarter of 2017, according to an analysis by the Cato Institute.

Then-candidate Trump said in a 2016 speech in Phoenix that "we will ensure that E-verify is used to the fullest extent possible under existing law, and we will work with Congress to strengthen and expand its use across the country." But so far, his focus has mostly remained on the wall.

Those who live and work on the border, from both sides of the political aisle, often talk about the need for practical and functional guest workers' programs to meet labor demands in industries such as agriculture, construction and hospitality through employees authorized to be in the country. There are several types of workers' programs available, but employers often say they can be too cumbersome, especially when dealing with time-sensitive crops.

And then there's foreign policy. “What we don’t like to talk about much,” said Kerlikowske, the former CBP commissioner, “is look at the success, the number reduction of people from Mexico coming into the United States or attempting to come into the United States. It’s pretty clear it's because Mexico’s economy has improved.”

When you look at the issues that are driving today's migrants, he said — corruption, crime, lack of educational opportunities, a poor economy — “if you were able to help these Central American countries improve in all of these areas, you would find people not willing to make that very dangerous trek.”